Tim Wu, the influential Columbia Law School professor who previously served in the Biden administration, is back with a message: Modern American capitalism has devolved into a system defined by the accumulation of market power and “extraction,” generating a profound sense of “economic resentment” across the nation.

Speaking to Fortune upon the release of his newest book, The Age of Extraction, Wu connected the current political volatility to a widespread feeling that “our system is not fair.” He suggests this pervasive anger stems from individuals feeling “out-powered, as opposed to out-competed,” which creates far more resentment than losing in a fair fight.

Wu defines the core problem as a shift in business goals: moving away from building “a good product that people want to buy because it’s good,” toward models seeking to “find power over someone and suck as much as you can out of them.” Wu agreed his take has many similarities to recent writings from his old friend, Cory Doctorow; even though Doctorow’s argument is mainly about tech, he acknowledged they share much of the same DNA. “I think that that is kind of an economy-wide problem. Everything kind of just creeps. It’s that weird feeling of something you like becoming worse.”

Chalking it up to a “lack of discipline,” Wu said too many companies let things drift in the modern age of extraction. Strong competitors, legal enforcement, and a company’s employees can all stress a sense of discipline, he said, “but none of those are very strong right now in so many markets …a lack of discipline lets firms get away with making their products and services worse.” Zooming out a bit further, this trend challenges the fundamental idea of American progress, especially in the tech industry, which is supposed to be the “invention industry” constantly driving improvement.

“My understanding of America is that it’s the place where things are supposed to get better,” Wu said. Living in an age when so many things are getting worse instead “cuts at the core of the idea of America, but also the tech industry [idea] of progress,” he argued—but he does see an unlikely solution.

As a sports fan, Wu said there’s a clear example of a market structure that has discipline, where things are not in fact getting worse, where things are not extracted. It’s a good product that people want to buy because it’s good: the National Football League. He said the NFL illustrates the importance of fair rules, with “aggressive rebalancing,” achieved through mechanisms such as the market cap, the draft, and adjusted schedules.

How the NFL could fix the economy

While the NFL is still competitive and meritocratic, it ensures that even the worst team “has some chance to get a great quarterback” and become competitive again, like the Kansas City Chiefs, who have enjoyed historic success with their franchise players Patrick Mahomes and Travis Kelce. Teams from smaller markets like Kansas City routinely dominating those from larger markets, like New York, would be unthinkable in “just an economic game,” Wu argued. In contrast, Wu points to Major League Baseball, which has been “distorted by out of control spending.” This results in an “absurd” mismatch of resources, where smaller teams are crippled by resource deficits, rather than poor play. (The big-market Los Angeles Dodgers, with the biggest payroll in baseball history, just celebrated their second-straight World Series win.)

The NFL’s success serves as a model for how the U.S. economy should function. “I’m not a socialist,” Wu told Fortune. “In some ways, I’m here to try to not destroy capitalism, but return it to what it can be.” In his new book, Wu writes about the “extractors” and the “extracted” in language that sounds similar to the K-shaped economy dominating headlines in 2025, a shorthand for an economy where the rich get richer and the poor get poorer. “I think it is closely linked,” Wu said, adding it wasn’t his intention to directly link them in his book.

“I think we have moved in the direction of an economy where the focus of business models is the accumulation of market power and then extraction, which, by definition, almost by basic microeconomics is going to result in a lot of [upward] wealth redistribution.” Wu added that he thinks many of the industries that used to provide a middle class or even upper middle class lifestyle “are being driven down in favor of a couple industries that have outsized returns,” including concentrated middlemen, certain parts of finance, and tech platforms.

If Americans love the NFL so much on their TV every Sunday, he argued, why not apply the same principles from the league to how we structure our society? After all, Wu points out, he’s been right about some things before, to society’s benefit.

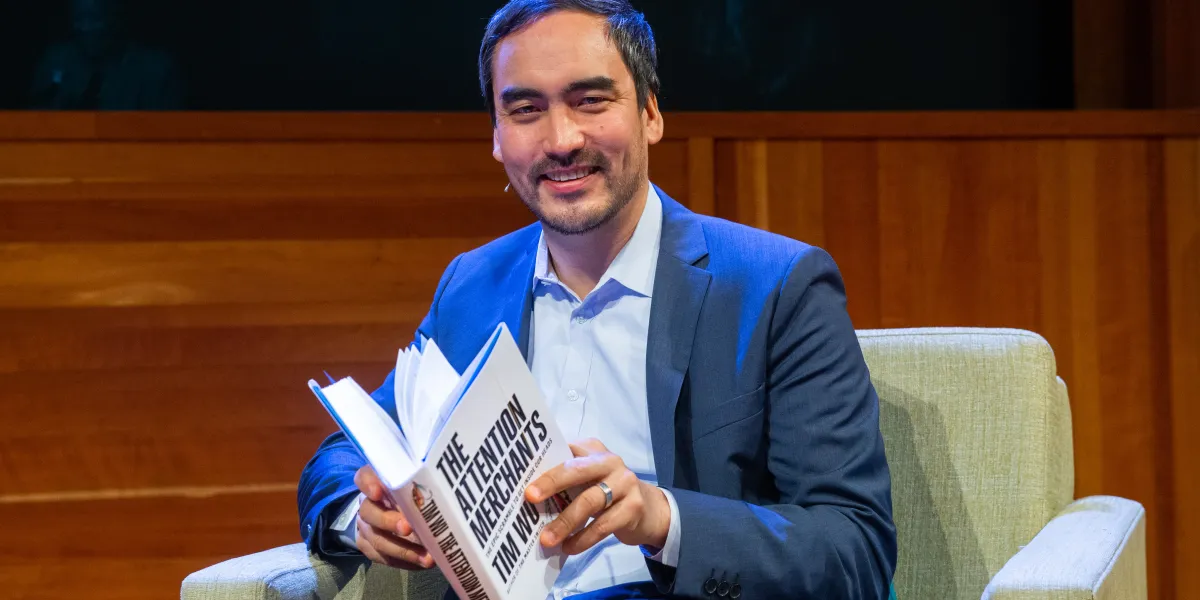

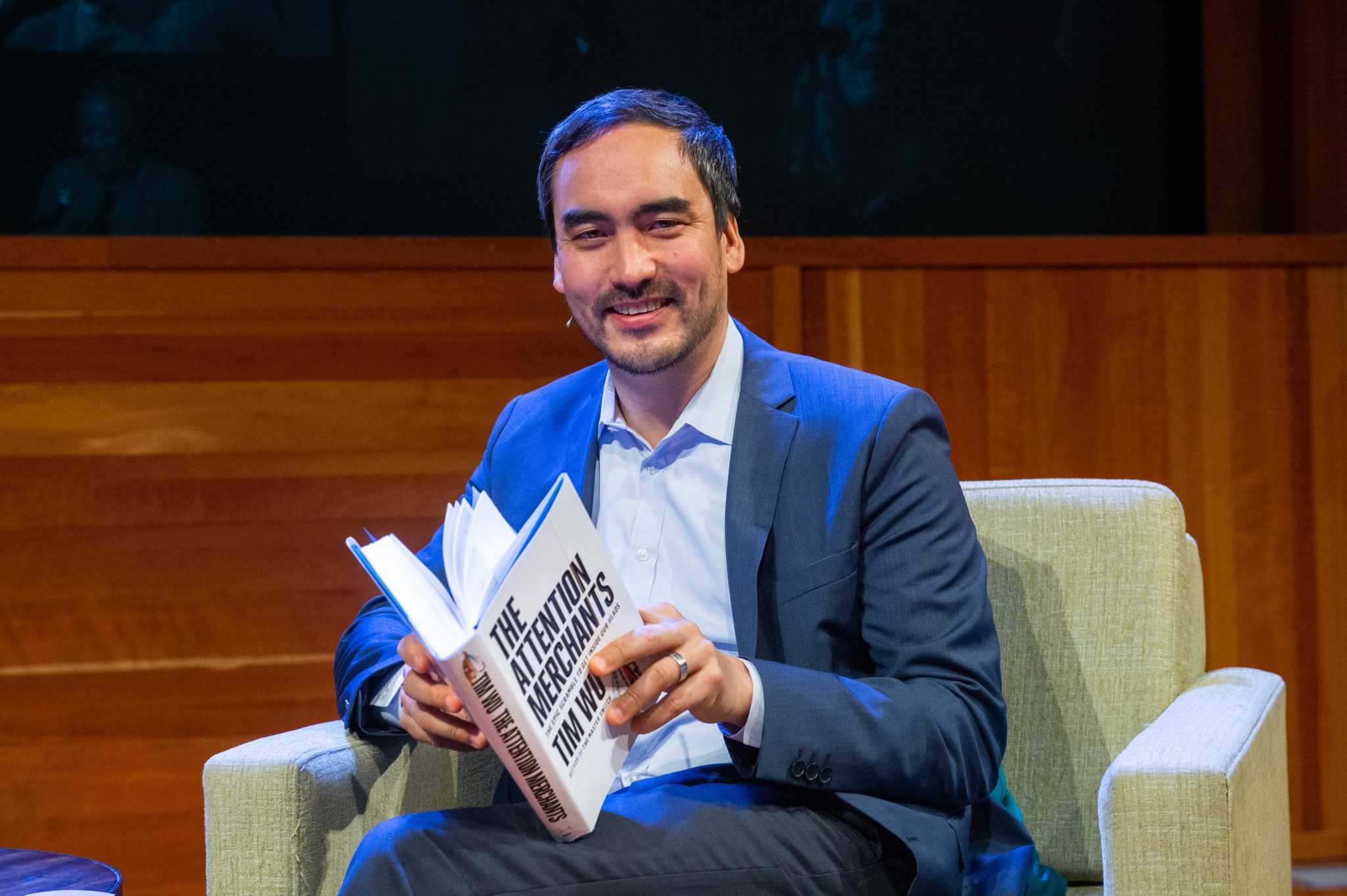

Net neutrality and attention

A distinguished professor at Columbia University who The New York Times described as “an architect of Biden’s antitrust policy,” Wu has not one but several big ideas to his credit. One is “net neutrality,” the concept authored by Wu over 20 years ago that internet service providers must be agnostic about what content flows through them. This was a clear victory, as the law is still on the books. Another is about “the attention economy,” a thesis and book (The Attention Merchants) that Wu released roughly 10 years ago, sounding the alarm on how attention was turning into a commodity in the internet age and was increasingly exploited.

Wu said he wants to be humble, but genuinely believes he was right about the attention economy a decade ago. “Maybe it was sort of obvious,” he said, but the resource of human attention becoming scarcer and more valuable and “companies are very sophisticated at essentially harvesting this resource from us at a very low price.”

As a parent (his kids are 9 and 12), Wu said he notices “people are much more sensitive” about their children using attention-economy products and believes there has been a counter-movement to reclaim attention. He notes large language models are becoming popular in a very similar way and there’s no advertising on them for now, so “it’s not like the problem has gone away and it’s not as if we are able to get away from our phones. I just think it’s better recognized.”

A dance with politics and the ‘beer wars’

In his conversation with Fortune, Wu reflected on his time in the Biden White House, saying it was “an important and great experience,” but he wishes they were able to do more on children’s privacy issues as he believes 99% of Americans would support legislation in this area. Yet, it was “impossible to get a vote on anything, any issue” when he worked in the White House. Congress “doesn’t want to let things get to a vote,” he said, attributing much of the gridlock to the fact that “influence of big tech over politics has just gotten so strong.”

When asked if he has any interest in working in government again, perhaps along his longtime friend Lina Khan in Zohran Mamdani’s mayoralty in New York, Wu only said he’s “very supportive of the new mayor.” He said he could get involved in politics in some fashion again, but is “much more in a family mode” these days. Wu has a perhaps surprisingly long history in public service, having worked in antitrust enforcement at the Federal Trade Commission as well as working on competition policy for the National Economic Council during the Obama administration. In 2014, Wu was a Democratic primary candidate for lieutenant governor of New York, where he first met Khan.

Wu did get involved in some intra-left economics squabbles recently, as he took Khan’s side of the debate on plans to reduce the price of hot dogs and beers at New York City sports stadiums. The “beer wars” erupted on Twitter, with Wu and Khan on the side in favor of cutting prices, and Matt Yglesias and Jason Furman on the more centrist side, arguing for letting the free market set prices. Wu said it was a “strange battle” and said there seems to be a tension on the left around economics that he doesn’t fully understand, adding that he has worked productively alongside Furman in the past. In general, he said he thinks “our politics is very angry, partially because of economic resentment … it gets expressed in strange ways and goes in all kinds of directions.” Tying it back to his new book, he believes that in general, “we let things go a little too far” and we “just kind of lost touch with the tradition of broad-based wealth that was the American way.”

When asked about the uproar among the New York business community about Mamdani and the term “democratic socialism,” Wu said it has become a bit of an “umbrella” term, because “a real socialist believes that all the means of production should be owned by the state” and Mamdani’s democratic socialists aren’t exactly advocating that. He said maybe some on the left would like more direct ownership of public things, but it’s more a mixture of that same “we’ve gone too far” feeling. Wu added that he personally feels most affiliated with Louis Brandeis, a judicial figure from the Progressive Movement who was influential in developing modern antitrust law and the “right to privacy” concept.

“If you want to talk about America drifting towards something more like Communism, it is more in this idea of real, very active state involvement” that you see in the Trump administration, which has, for instance, taken stakes in major U.S. companies such as Intel. “That’s actually more like socialism” and what you see in a “command economy,” Wu said. He compared it to Stalinism or fascism under Mussolini, “neither of which are the most flattering labels, I realize.” It’s also, of course, similar to Chinese Communism, Wu said.

Wu said he hopes this doesn’t come to pass. There could be an America where the idea of doing business is extraction—trying to find power over someone and sucking out as much as possible—and another, better way. “I think we can do better. I’m a big believer, frankly, in business. I think we need a return to like this idea you can reap what you sow, that your investments will get you somewhere.”