At the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, the U.S. government approved record-breaking spending bills totaling $5 trillion in a bid to keep businesses afloat, people employed, and the economy from tipping into recession. Five years on, and somehow, the American economy has not only avoided a contraction but has managed to grow—an outcome many investors thought impossible.

Come 2025, the White House has announced another major round of stimulus in the form of President Trump’s One Big, Beautiful Bill Act. Projections from the nonpartisan organizations Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) place the price tag of the act—the additional burden onto the national debt—at around $3.4 trillion.

While most economists agree that the revenues generated by tariffs will offset the majority of this spending, the fact remains that an eye-watering amount of stimulus is being pumped into the economy at a time when it is not only already stable, but growing.

Further stimulus is expected in the form of rate cuts from the Federal Reserve. Despite inflation sticking at approximately 3%—above the Fed’s 2% target—voting members of the Federal Open Market Committee have indicated their openness to multiple cuts, with Trump-appointee Stephen Miran even advocating for a 50bps cut reduction before the year is out.

This poses the question of why, between the central bank and the White House, Washington is acting like the U.S. is in a recession—or is at least preparing for one.

The Fed’s cuts could be coming for a range of reasons: The central bank may truly believe its monetary policy, at 100 bps above inflation, is too restrictive. Or its board members could be vying for Trump’s attention to replace Chair Powell next year. Or, perhaps, it sees weakness in economic data, which it is trying to get ahead of.

Citadel CEO Ken Griffin has already broached the issue. Speaking at a conference in New York earlier this month, Griffin said Trump 2.0’s policies were creating a “sugar high” in the markets courtesy of their pro-growth agenda. Even then, he warned further stimulus action may be more suited to a recession than a “period of near full employment a few years into the business cycle.”

Does Washington know something we don’t?

Washington policy—from the central bank or the White House—might make more sense if America was in a recession. According to Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s, that’s effectively the case for more than half the states in the U.S. In a recent note, Zandi found that 23 U.S. states’s economies are contracting, just 16 are seeing economic growth, and 12 are classified as “treading water.”

Zandi previously told Fortune that consumer sentiment for many people is in line with a recession, bar the fact they currently have jobs: “The way people perceive their own economy, their own finances, are very consistent with the recession—the difference here is they’re not losing jobs. Having said that, we’re at a 4.3% unemployment rate … Even in a recession, we got 5% or 5.5%, so we’re talking about a percentage point … It’s not a lot of people. You could argue that that’s not a very good litmus test of whether you’re in recession or not.”

But Zandi told Fortune in an exclusive interview that the White House certainly isn’t charting its course based on this concern: The aim of the OBBA, he believes, is to create enough positive sentiment to propel the administration through the midterms next year.

The Fed, however, is another story: “The Fed is putting a lot more weight on growth and jobs. They’ve seen the job market go sideways … unemployment is low, but it’s on the rise, particularly for young people, and I think that is paramount. They’re weighing down the inflation risk because inflation expectations are still anchored and [the Fed] feels like the increase in inflation [by] tariffs will be more of a one-off, less persistent.”

Zandi adds that the Fed is “rightly” concerned about its independence. “I think they desperately want to avoid a recession because if we do have one, they will get blamed and their independence will be much more severely threatened as a result. So I think they are calculating that much better to err on the side of supporting growth, much less worrying about inflation down the road.”

At the other end of the spectrum, Macquarie’s chief economist, David Doyle, tells Fortune that while Washington isn’t necessarily shaping its policy because of imminent recessionary fears, policymakers will be keen to maintain growth. That is a fine balance to maintain, he warned, which could tip too far towards over-stimulating the economy: “If they’re successful—the Fed and the administration is jointly successful and they avoid a recession—in 2026, maybe the risk then becomes the other way: Is there an overheating?”

Doyle added that there’s a “good chance” that people start talking about Fed rate hikes next year. “Inflation looked like it had been on a steady path down and now it looks like it’s stalling out around 3%. And if we do see the labor market pick up, and potentially more tariff price pass-through … then inflation is more elevated in 2026.”

Is current policy appropriate?

While Washington policy may avert disaster in the near term, the question remains whether it’s appropriate to approve such massive stimulus in a period of the economic cycle that is relatively stable, especially given the recent government shutdown (which occurred precisely because of an argument in Congress over spending).

The 2025 shutdown has occurred because Democrats want to see extensions of tax credits and continued spending on health agencies, both actions which come directly out of federal government funds. While Republicans are opposed to this expense, they have been willing to extend and approve tax cuts reducing federal revenues to the tune of $4.5 trillion, per calculations from the Bipartisan Policy Centre.

Theoretically, governments should run larger deficits during periods of higher unemployment: They’re spending more money to stimulate the economy while receiving less tax revenue from put-upon workers. Budgets should be more balanced when economic times are good, when there is less need for government stimulus and greater opportunities to grow tax revenue.

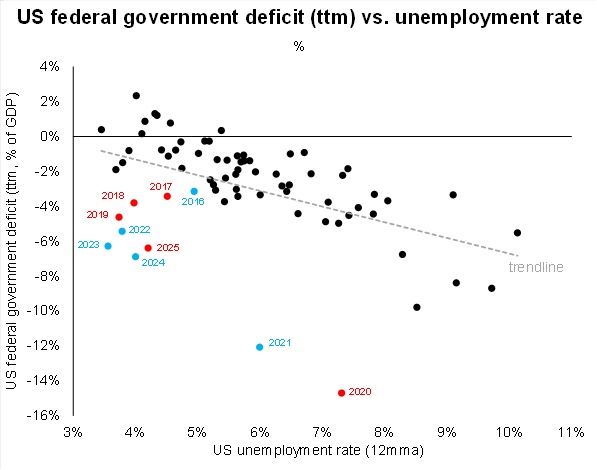

With national debt now closing in on $38 trillion, Macquarie’s research found that since 2018, governments (irrespective of party) have added to the deficit at greater levels than the historical average under similar economic conditions. Plotting the U.S. unemployment rate against the federal deficit as a percentage of GDP, Macquarie found that historically an unemployment rate of approximately 5% would result in a -1% change to the deficit. This pre-2018 correlation tracks steadily downward as unemployment rises, with an 8% unemployment rate resulting in a -4% change to the deficit.

That correlation shifted in 2018, demonstrating that macroeconomic conditions and federal budgets have become increasingly disconnected. For example, a relatively stable 4% unemployment rate in 2019 still saw the deficit shift by -4%, while a similar unemployment level in 2024 saw it drop a further -6%.

“The key takeaway I tell our clients in this is: Normally when you have unemployment that’s 4% the deficit would be like -1% or even (can you believe it?) a balanced budget. Now we’re in a regime where it’s like -6, -7%, that’s a wider structural deficit. That’s a problem, and what it means is that if we do enter a recession and unemployment, let’s say it blows out to 7% or something, you’re probably talking about a deficit that’s —12%,” Doyle added.

“How is the United States going to fund its long-run obligations and how would it fund its deficit in that situation?” Doyle asks.

The point at which investors begin to question debt viability isn’t simply down to the volume of debt (after all, government borrowing provides the basis for the bond market which is one of the pillars of the global economy) but whether a nation has the ability to repay or service its debts, or will resort to quantitive easing to balance the books and dilute the value of the investment. This is why economists are so preoccupied with a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio, basically whether a country is growing enough to justify its borrowing, which is projected to spiral to 156% by 2055 according to the CBO.

If the current fiscal package is estimated to not only cover its costs but grow the economy too, the path is justified, argued Zandi. “With the One Big Beautiful Bill you get some stimulus: it’s already stimulatory and is adding some stimulus, so from that perspective it’s not unprecedented,” he added.

Yet stimulatory or not, America’s economy has a mountain to climb before Washington’s debts align more appropriately with its economic context. Zandi added: “The amount of support to the economy which has been there since the pandemic, we’ve never seen anything like that. The primary deficit should be at zero, should be in surplus, when you’re in full employment.”

Even “relatively modest and small” stimulus is likely adding to concerns about debt, Zandi noted. “We’ve already got these massive deficits and debt and we’re doing nothing about it—just the opposite. So it’s unprecedented in that sense.”