Three finance professors have ruffled the feathers of one in every of Wall Road’s most vocal hedge fund managers with a brand new paper. “Beyond the Status Quo: A Critical Assessment of Lifecycle Investment Advice” estimates that “Americans could realize trillions of dollars in welfare gains” by adopting an “all-equity strategy” for his or her retirement financial savings.

It’s a severe problem to some bedrock rules of recent investing, significantly the concept diversifying throughout asset courses, i.e. shares and bonds, is probably the most logical selection for long-term traders. The paper’s authors, professors Aizhan Anarkulova of Emory College, Scott Cederburg of the College of Arizona, and Michael S. O’Doherty of the College of Missouri, got here round to an all-stock funding technique after reviewing the historical past of 38 developed markets between 1890 and 2019.

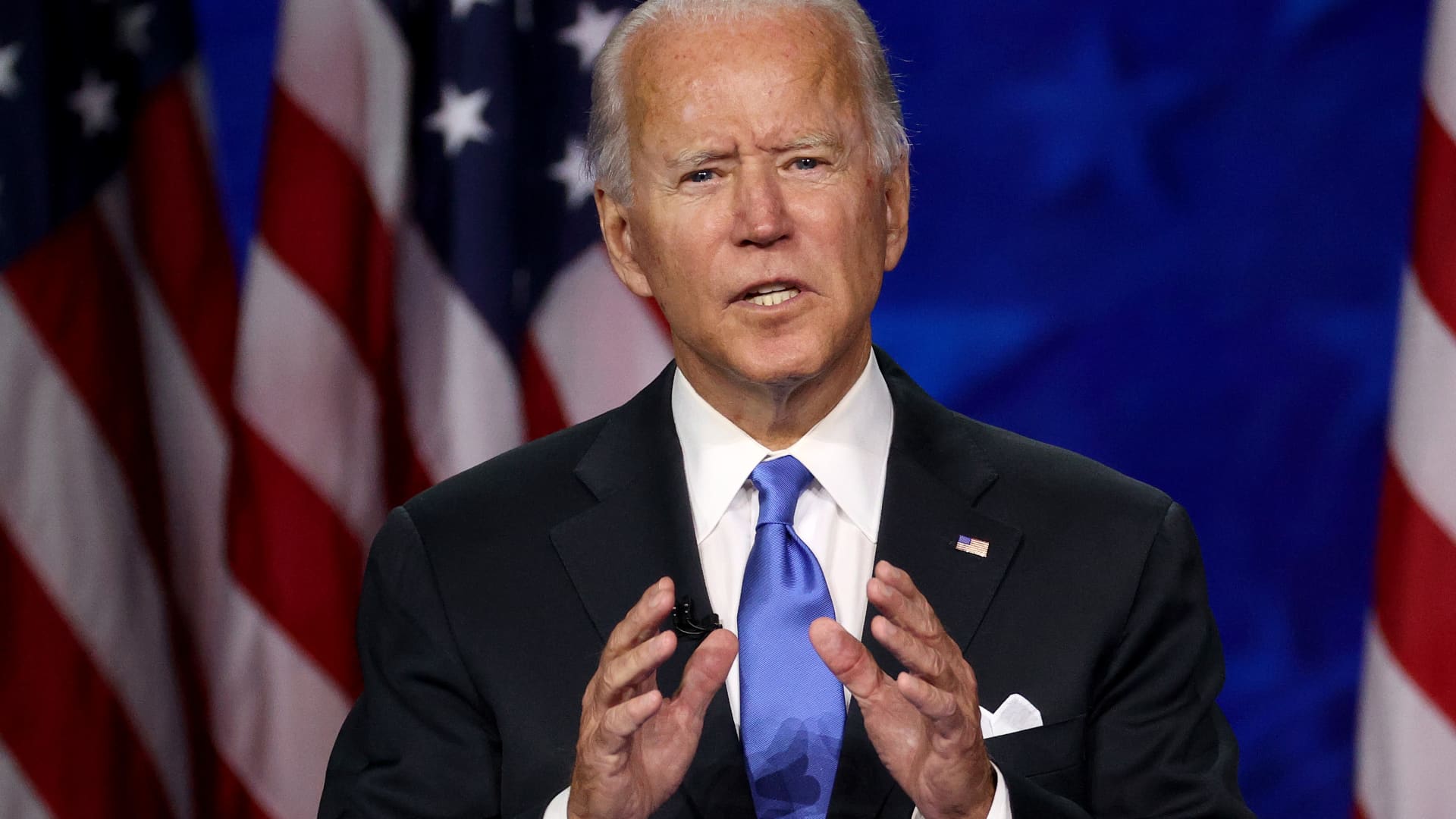

However Clifford Asness, the billionaire cofounder and chief funding officer of the world’s third-largest hedge fund, AQR Capital Administration, isn’t shopping for it.

“Simply looking at historical results and urging investors to ‘buy the thing that’s gone up the most over the long term’ is not financial analysis, it is finger painting,” the Wall Road veteran, who undoubtedly isn’t recognized for pulling his punches, argued in a Monday article titled “Why Not 100% Equities.”

Asness had a number of particular critiques of “Beyond the Status Quo”—however they aren’t actually new. The truth is, the hedge funder, recognized for his quant worth methods, has been battling arguments for 100% fairness portfolios with “alacrity and panache” (his personal phrases) for the reason that Nineties. He even used the identical title, “Why Not 100% Equities,” in 1996 to refute the findings of a paper that “presented strong evidence documenting the historical superiority of investing in 100% equities.”

In response to Asness, the concept traders ought to put all their monetary eggs into one basket doesn’t account for a vital function of monetary markets: threat. “We (academics, practitioners, anyone who’s taken a cursory look at modern finance) prefer a diversified portfolio because we believe it has a higher return for the risk taken, not a higher expected return,” he defined.

The talk over risk-adjusted returns—and why leverage issues

That brings us to what the main portfolio technique of our period, trendy portfolio idea (MPT), typically calls “risk-adjusted returns.” When the Nobel Prize–successful economist Harry Markowitz first described the speculation that spawned MPT in a paper referred to as “Portfolio Selection” within the Journal of Finance in 1952, he argued that correct portfolio building requires traders to investigate each return and threat. The speculation gained loads of traction, and at the moment traders will typically measure the return of their portfolio solely after contemplating how a lot threat was taken to earn it.

This concept is used because the justification for diversifying into completely different asset courses with completely different threat profiles, and it has helped help the now-common perception {that a} portfolio allotted to 60% shares and 40% bonds is probably the most logical possibility for many long-term traders.

However there’s a caveat to MPT’s central tenet, which holds that risk-adjusted returns are superior to anticipated returns that don’t account for threat: Getting one of the best return typically requires using leverage, and most retirement savers aren’t leveraging their portfolios.

Even Asness defined: “If the best return-for-risk portfolio doesn’t have enough expected return for you, then you lever it (within reason). If it has too much risk for you, you de-lever it with cash. Remarkably this has been shown to work.”

He’s proper that this tactic has been proven to work, however can it actually be utilized by the typical American? In an announcement to Fortune, Anarkulova, Cederburg, and O’Doherty famous that their research centered on retirement savers, and the “vast majority” of those traders usually are not allowed or not ready to make use of leverage.

“It is possible that some other portfolio could be levered up and be better than the all-equity strategy for hypothetical investors who are able to use leverage for their retirement savings,” they defined in written feedback, including that they’ll “examine these cases in the next version of the paper.”

However total, the professors stated that their evaluation suggests “that any such portfolio will remain dominated by stocks and will not include much (if anything) in bonds for reasonable leverage levels.”

However don’t take the concept leverage is important for MPT from the professors—take it from two principals at Asness’s personal agency, AQR. In 2014, AQR’s Andrea Frazzini and Lasse Heje Pedersen defined in a paper that “many investors, such as individuals, pension funds, and mutual funds, are constrained in the leverage that they can take, and they therefore overweight risky securities instead of using leverage.” In different phrases, with the intention to get the good points you need utilizing a portfolio designed for risk-adjusted returns, you may need to make use of leverage; and if you happen to don’t, the lure of “risky” shares with increased absolute returns is all the time there. That lure could also be extra of a siren music (Asness would possible argue so), however that’s up for debate.

Trillions in welfare good points?

So the disagreement over using diversified portfolios that maximize risk-adjusted returns might come right down to leverage, one thing that’s extra generally utilized by skilled traders moderately than your common Joe. However Asness additionally had a number of different factors of rivalry with this new paper value addressing.

Crucial of those is the paper’s declare that by switching to 100% fairness portfolios, U.S. retirees might get “trillions in welfare gains.”

Asness argued that there’s a flaw within the logic behind this concept. The declare that trillions of {dollars} are “being left on the table is really just non-economic hype” based mostly on the inaccurate assumption that there are “sidelines” within the investing world, he defined. Asness famous that shares are all the time 100% owned, and on the planet of finance, there aren’t any sidelines, simply traders holding various kinds of belongings.

“If some investors read this ‘new’ paper and decide to buy more equities, they have to buy those equities from other investors. This can force the price up, and the expected future return down, but everyone can’t suddenly have double the normal amount of equity dollar return out of thin air,” he defined.

In response, the professors stated that they “don’t disagree” that if all retirement savers switched to 100% shares, “the additional demand for stocks would raise prices and lower expected returns,” which might alter the “optimal” portfolio to one thing apart from 100% equities.

Nevertheless, they supplied a few explanations for his or her concept (I’ll allow you to choose their validity by yourself). First, they claimed that retirement savers with 100% fairness portfolios would have the ability to save extra earnings yearly than their friends with conventional diversified retirement portfolios (14% vs. 10%) because of elevated market returns. That might supply a severe financial advantage of over $200 billion a 12 months, they stated.

Second, they argued that if most traders don’t shift to the all-equity technique, which is probably going, then “those who do will get their portion of the benefit and overall stock prices aren’t likely to move too much so all-equity would remain a good strategy.”

Nonetheless, the professors admitted that they plan to take away the “trillions of dollars” line from their subsequent draft of this paper. They concluded by saying: “it’s at least tough to argue with our simple point that the economic magnitudes of differences in strategy performance are large.” Make of that what you’ll.

Sampling points?

Lastly, Asness talked about sampling bias as a possible subject with the “Beyond the Status Quo” paper. He claimed that rising valuations in the course of the measured interval have created an “overestimation” of the longer term efficiency of shares. However the professors pushed again on this one, noting that they used knowledge from 38 developed nations, for a pattern interval of over 100 years, and U.S. shares solely made up 5% of the info.

“We aren’t sure what to make of this criticism,” they wrote. “We carefully constructed our sample to mitigate the sort of lookahead bias that seems to be referred to in the comment… Our sample contains a very large amount of information about stock and bond performance with a variety of market conditions across countries and time, so we believe it provides investors with a balanced and comprehensive view of potential outcomes.”

Sampling points apart, the controversy over trendy portfolio idea, in addition to the validity of risk-adjusted returns and diversification, isn’t going wherever quickly. Asness argues that challenges to this standard knowledge are a function of intervals of inventory market outperformance.

“The bottom line is diversification works, theory works (eventually), owning one asset is suboptimal, extrapolating the winning country over a period of valuation increases is dangerous, finance 101 is actually helpful—and we’ll likely have to do this again after the next bull market,” he concluded.

Is he proper? Properly, I’ll go away that one as much as you.