For the secretive billionaire Besnier family, the recent recall of potentially dangerous infant formula made by its nearly century-old firm brings an uncomfortable feeling of deja vu.

Just eight years ago, the French clan behind Groupe Lactalis, the world’s biggest dairy company, and its chief executive officer — third-generation scion Emmanuel Besnier — went through a similar crisis after dozens of infants who consumed formula produced at one of its plants in western France were poisoned by salmonella. Lactalis was criticized for acting too slowly and charged for failing to recall the product, deception and involuntary injuries. The case is ongoing.

Now, fears that baby milk powder has been tainted with a toxin that can cause vomiting, diarrhea or worse have forced Lactalis and better known food giants Nestle SA and Danone SA to pull products from store shelves around the world over the last few weeks. French authorities are investigating whether two infant deaths are linked to consumption of Nestle’s Guigoz brand.

As recalls, threats of lawsuits and accusations of regulatory failures filled the airwaves, Nestle and Danone were punished in the stock market.

For closely held Lactalis, which announced its baby formula recall on Jan. 21 — about two weeks after Nestle first began pulling its own products — the spotlight is turning to its controlling family, with questions about whether they moved quickly enough.

“In the case of Lactalis, the family is ultimately accountable,” said Philippe Pele-Clamour, an adjunct professor at business school HEC Paris who specializes in family firms. “This can be a problem in crisis management.”

The current scandal involving baby formula makers stems from the possible presence of cereulide, a toxin traced to contaminated arachidonic acid oil, or ARA, from a Chinese supplier. Lactalis said an alert from a French trade body prompted it to “immediately” test its milk powder.

Initial analysis showed both the ARA ingredient and the finished product were “compliant” but later tests on prepared formula “revealed the presence of cereulide,” it said. Its recall of infant formula marketed under the “Picot” brand and other labels touched 18 of the 47 countries where they are distributed. Lactalis told Bloomberg News it has stopped using the Chinese supplier identified as problematic and has started asking other suppliers for a guarantee on the absence of cereulide.

Both incidents have served to shine a light on the Besniers and the gigantic dairy-based empire they’ve cobbled together over the years through acquisitions, giving them unmatched clout in the industry and frequently throwing them in the midst of controversies. The No. 1 player in the sector, with cheeses, butter, yogurt and other milk products carrying labels like President, Galbani, Parmalat, Yoplait and Kraft, the group has seen its sales grow about six-fold in two decades to reach a record €30 billion in 2024 — the latest available figure.

Yet over the years, Emmanuel Besnier and his two siblings have kept a low profile, rarely granting interviews or giving press conferences even as repeated crises earned them bad publicity. Their company is a frequent target of French farmers who accuse it of not paying enough for raw milk. It has also been in the cross hairs of tax authorities. Besnier declined a request for an interview.

There’s little to suggest the current incident will dampen the clan’s ambition to push further into the $51 billion global baby formula industry. Just months after the salmonella scandal, Lactalis announced the acquisition of Aspen Group’s infant formula business for €740 million, giving it brands like Alula and Infacare sold in Africa, Asia and Latin America. It also said it planned to “develop a global infant nutritional business.”

While it’s unclear whether that still stands after the latest health scare, the Besnier clan appears determined to remain dominant in milk. In a rare interview last year with French financial daily Les Echos, Emmanuel Besnier said the commodity is the company’s backbone, with diversification focused on expanding geographically and into related products like yogurt.

“Lactalis is a long-term believer in the dairy space,” said Mary Ledman, a former strategist at Rabobank who’s now at industry publication The Daily Dairy Report. “They don’t have to worry about quarterly earnings and that has most certainly contributed to their success.”

Based in the northwestern France, the Besniers over the course of three generations have expanded what began as an artisanal cheese-making operation into a multinational entity with products sold in some 150 countries. The three siblings who own the group — Jean-Michel, 58, Emmanuel, 55, and Marie, 45 — are now worth a combined $18 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index. Jean-Michel and Marie are directors at the family’s holding company B.S.A.

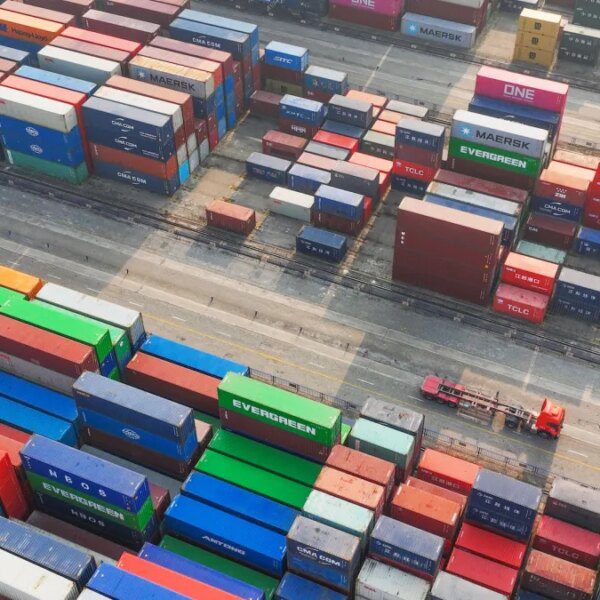

The media-shy trio’s fortune illustrates the global reach of a clutch of French families who oversee firms built from small operations into industry giants through expansion and acquisitions. France dominates the luxury sector through companies like LVMH, founded by billionaire Bernard Arnault, and Hermes International, whose controlling family is Europe’s wealthiest. The Dassault heirs hold global sway in fighter and business jets while the second-generation Saades control the world’s third largest container shipping line, CMA CGM.

In the case of Lactalis, founder Andre Besnier made his first 17 Camembert cheeses in 1933 branded “Le Petit Lavallois,” using milk collected near his hometown of Laval, where the company is still based. He expanded over the years into products like butter and cream. After Andre died in 1955, his son Michel took over, creating the President brand, exporting brie to the US and making the group’s first acquisitions. Michel died suddenly in 2000 and Emmanuel took the helm at age 29.

As CEO he’s proved to be an aggressive deal-maker, overseeing some 124 acquisitions worth billions of dollars, ranging from Italian mozzarella-maker Galbani and Brazilian milk producer Itambe to General Mills’ yogurt business in the US that includes Yoplait and Kraft Heinz cheese brands like Cracker Barrel.

“If they see a target and they want it, they will most likely be the buyer,” Ledman said.

Rabobank said in its 2025 ranking of the world’s 20 biggest dairy companies that “Lactalis’ appetite for acquisitions appears insatiable,” noting its global dominance and comfortable lead over No. 2 Nestle.

While the deals have put Lactalis on the industry’s map as a major player, the group has also had its share of bad news. Repeated clashes with French farmers over milk pricing have taken their toll. A 2016 dispute was particularly noisy, descending into a war of words and leading to government intervention and a concession by Lactalis to raise the rate. The playbook was similar over food inflation coming out of the pandemic.

Lactalis and the Besniers have also found themselves at odds with French tax authorities. In 2024, the company agreed to pay €475 million to the administration as part of a dispute over international financing through Belgian and Luxembourg entities, according to a filing. The settlement came as political discourse over tax-the-rich policies has intensified in France and helped push net profit down to €359 million in 2024. The family holding company B.S.A.’s debt stands at €12 billion, according to Bloomberg data.

Through all their troubles, the family has kept a stony silence, something one can expect again as it traverses its current woes, Pele-Clamour said.

“The Besnier family has long clung to a culture of opacity,” he said. “They are rooted in a place that’s far from Paris and other big capitals which helps them to remain discreet.”