Governments throughout Asia—in Singapore and Beijing, Tokyo and Seoul—are going through a crisis: plummeting beginning charges.

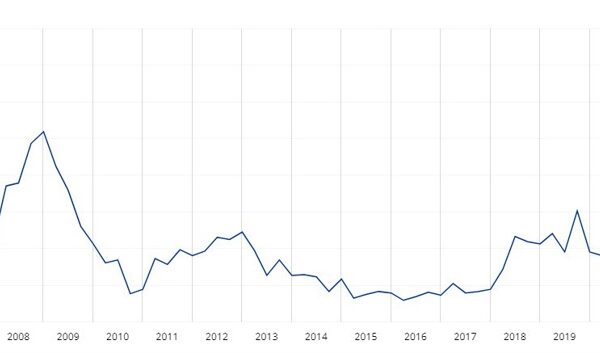

For a number of many years now, folks in East Asian economies have had fewer and fewer kids. Final yr, South Korea beat its personal document for having the world’s lowest beginning charge, reporting 0.72 births per lady for 2023, down from 0.78 in 2022. Singapore reported 0.97 births per lady, the primary time the speed has fallen under one. Japan has one of many world’s oldest populations, with a median age of 49.5. Hong Kong, Taiwan, and mainland China are all reporting falling beginning charges as effectively.

All of those economies have fertility charges far under 2.1, the “replacement rate” which permits for a steady inhabitants. They haven’t reported a charge above 2.1 for years, if not many years.

A low beginning charge results in a shrinking inhabitants, and a smaller workforce to provide the products and providers that result in financial development. Slower financial exercise leads to drops in fiscal income, giving fewer assets to a authorities that now wants to offer welfare for a rising aged inhabitants.

Teachers typically level to the price of childcare, poor work-life steadiness, a scarcity of assist for brand spanking new dad and mom (notably moms), and the stresses of contemporary society as causes for falling beginning charges. “In all the cosmopolitan cities, the fertility rate tends to be much lower because [people have] a lot of choices. The higher the development, [the] more urbanized, the more education that women get, the smaller the family size,” Paul Cheung, director of the Asia Competitiveness Institute on the Lee Kuan Yew Faculty of Public Coverage, says.

Confronted with this looming disaster, Asian governments have turned to an easy resolution: Give potential dad and mom money if they’ve children. The connection is easy to grasp. If a significant barrier to having kids is the price of childcare, then assuaging that price with further money ought to change somebody’s financial calculus.

Besides it hasn’t labored. Even Singapore, which Cheung suggests had a “way more generous [policy] than all the Asian countries,” has not succeeded in arresting the decline in fertility.

“Low birth rates are a reflection of big institutional, cultural, structural problems,” mentioned Stuart Gietel-Basten, a professor of social science and public coverage on the Hong Kong College of Science and Know-how. “Throwing a bit of money at it is not going to fix it.”

What are governments at the moment doing to cease falling beginning charges?

Cheung, earlier than his stint as an instructional, was the director of Singapore’s inhabitants planning unit between 1987 and 1994. He helped begin Singapore’s pronatalist coverage, providing a comparatively extra beneficiant set of incentives to encourage extra births. The federal government even organized occasions to assist single Singaporeans to satisfy.

Singapore’s authorities formally inaugurated its child bonus scheme in 2001. Probably the most current payout is 11,000 Singapore {dollars} ($8,263) for every first and second little one and 13,000 Singapore {dollars} ($9,766) every for the third and subsequent little one.

Different governments are additionally attempting to dole out incentives. Japan elevated its lump-sum childbirth profit to 500,000 yen ($3,400) in April final yr. Beginning this October, the federal government may also offer 15,000 yen ($102) a month to households after the beginning of a primary and second little one till the age of two, after which proceed offering 10,000 yen ($68) until highschool. The federal government will provide more cash to households with greater than two kids.

South Korea has increased its incentives, too. The federal government provides 2 million Korean gained ($1,519) to oldsters when a child is born, which will increase to three million gained ($2,279) for the second little one. Dad and mom may also get an allowance of as much as 18 million gained ($13,674) in complete for the primary two years of the kid’s life.

Hong Kong, then again, is offering a one-off money allowance of HKD 20,000 ($2,557).

Singapore’s beginning charge is declining at a slower tempo than that of different Asian economies, solely falling under 1.0 final yr. (By comparability, Hong Kong’s fertility charge first fell under 1.0 in 2001, and hovered round that degree earlier than falling again under 1.0 once more in 2020). Singapore’s inhabitants continues to be steady, however which may be the results of the nation’s extra liberal immigration insurance policies, in contrast with Japan and South Korea.

All these measures appear to do is “delay the population decline a little into the future,” Cheung says.

‘I feel sorry for the government’

The scary thought for demographers might now be that there’s no simple repair for falling fertility. Even Nordic nations, whose extra beneficiant pro-child insurance policies have been credited with protecting beginning charges comparatively excessive, have seen fertility collapse after the COVID pandemic.

“The strange thing with fertility is nobody really knows what’s going on,” Anna Rotkirch, a analysis director at Household Federation of Finland’s Inhabitants Analysis Institute, told the Monetary Instances earlier this yr. The demographer, who suggested former prime minister Sanna Marin on inhabitants coverage, now thinks fertility decline is “not primarily driven by economics or family policies. It’s something cultural, psychological, biological, cognitive.”

Analysis from Singapore implies {that a} drop in fertility might be the results of one thing extra elementary in how folks reside in fashionable society. Tan Poh Lin, a analysis fellow on the Nationwide College of Singapore, found charges of sexual activity amongst married heterosexual {couples} in Singapore—a “high-stress” society—have been decrease than the perfect frequency to conceive, typically thought-about to be 5 or 6 instances each 30 days. There have been “strong negative effects of both stress and fatigue, especially during weekdays,” she writes. Different surveys in Japan and South Korea report comparable findings.

But when financial incentives or higher social welfare applications and work-life steadiness, as in northern European nations, are usually not getting beginning charges to what they need to be, then what can Asian economies do to lift them?

“I feel sorry for the government because it’s the only organization or institution doing anything,” Gietel-Basten mentioned. “In reality, everyone has to take responsibility for this. Companies have to change their attitude and recognize children are a social good, and that parents should be supported and not penalized,” he says. “But that costs money.”

Some corporations in Asia have made high-profile gives to assist staff having kids. In February, a South Korean building agency, the Booyoung Group, offered a bonus value 100 million gained ($76,000) to encourage feminine staff to have kids. China’s Journey.com Group additionally offered some staff a ten,000 yuan ($1,391) annual bonus for households for each little one beneath the age of 5.

However there’s no fast resolution, says Gietel-Basten. As an alternative, he means that governments give attention to different financial well-being points—like youth unemployment, job safety, and a way that work is being valued—and hope that not directly improves fertility charges.

In mainland China, “there’s not even jobs for the young people who are alive now,” he says. “Why do you want to have more children?”