As if losing your job when the startup you work for collapses isn’t bad enough, now a security researcher has found that employees at failed startups are at particular risk of having their data stolen. This ranges from their private Slack messages to Social Security numbers and, potentially, bank accounts.

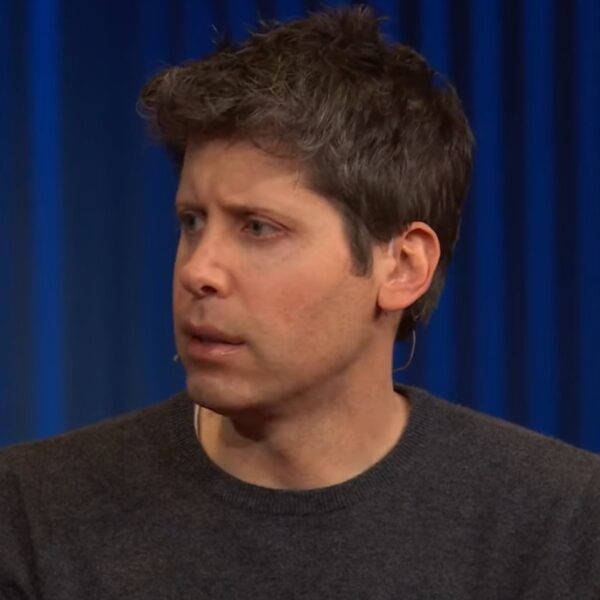

The researcher who discovered the issue is Dylan Ayrey, co-founder and CEO of Andreessen Horowitz-backed startup Truffle Security. Ayrey is best known as the creator of the popular open source project TruffleHog, which helps watch for data leaks should the bad guys gain identity login tools (i.e., API keys, passwords, and tokens).

Ayrey is also a rising star in the bug-hunting world. Last week at security conference ShmooCon, he gave a talk on a flaw he found with Google OAuth, the tech behind “Sign in with Google,” which people can use instead of passwords.

Ayrey gave his talk after reporting the vulnerability to Google and other companies that could be affected and was able to share the details of it because Google doesn’t forbid its bug hunters from talking about their findings. (Google’s decade-old Project Zero, for example, often showcases the flaws it finds in other tech giants’ products like Microsoft Windows.)

He discovered that if malicious hackers bought the defunct domains of a failed startup, they could use them to log in to cloud software configured to allow every employee in the company to have access, like a company chat or video app. From there, many of these apps offer company directories or user info pages where the hacker could discover former employees’ actual emails.

Armed with the domain and those emails, hackers could use the “Sign in with Google” option to access many of the startup’s cloud software apps, often finding more employee emails.

To test the flaw he found, Ayrey bought one failed startup’s domain and from it was able to log in to ChatGPT, Slack, Notion, Zoom, and an HR system containing Social Security numbers.

“That’s probably the biggest threat,” Ayrey told TechCrunch, as the data from a cloud HR system is “the easiest they can to monetize, and the Social Security numbers and the banking information and whatever else is in the HR systems is probably pretty likely” to be targeted. He said that old Gmail accounts or Google Docs created by employees, or any data created with Google’s apps, are not at risk, and Google confirmed.

While any failed company with a domain for sale could fall prey, startup employees are particularly vulnerable because startups tend to use Google’s apps and a lot of cloud software to run their businesses.

Ayrey calculates that tens of thousands of former employees are at risk, as well as millions of SaaS software accounts. This is based on his research that found 116,000 website domains currently available for sale from failed tech startups.

Prevention available but not perfect

Google actually does have tech in its OAuth configuration that should prevent the risks outlined by Ayrey, if the SaaS cloud provider uses it. It’s called a “sub-identifier,” which is a series of numbers unique to each Google account. While an employee might have multiple email addresses attached to their work Google account, the account should have only one sub-identifier, ever.

If configured, when the employee goes to log in to a cloud software account using OAuth, Google will send both the email address and the sub-identifier to identify the person. So, even if malicious hackers re-created email addresses with control of the domain, they shouldn’t be able to re-create these identifiers.

But Ayrey, working with one affected SaaS HR provider, discovered that this identifier “was unreliable,” as he put it, meaning the HR provider found that it changed in a very small percentage of cases: 0.04%. That may be statistically near zero, but for an HR provider handling huge numbers of daily users, it adds up to hundreds of failed logins each week, locking people out of their accounts. That’s why this cloud provider didn’t want to use Google’s sub-identifier, Ayrey said.

Google disputes that the sub-identifier ever changes. As this finding came from the HR cloud provider, not the researcher, it wasn’t submitted to Google as part of the bug report. Google says that if it ever sees evidence that the sub-identifier is unreliable, the company will address it.

Google changes its mind

But Google also flip-flopped on how important this issue was at all. At first, Google dismissed Ayrey’s bug altogether, promptly closing the ticket and saying it wasn’t a bug but a “fraud” issue. Google wasn’t completely wrong. This risk comes from hackers controlling domains and misusing email accounts they re-create through them. Ayrey didn’t begrudge Google’s initial decision, calling this a data privacy issue where Google’s OAuth software worked as intended even though users still could be hurt. “That’s not as cut and dry,” he said.

But three months later, right after his talk was accepted by ShmooCon, Google changed its mind, reopened the ticket, and paid Ayrey a $1,337 bounty. A similar thing happened to him in 2021 when Google reopened his ticket after he gave a wildly popular talk about his findings at cybersecurity conference Black Hat. Google even awarded Ayrey and his bug-finding partner Allison Donovan third prize in its annual security researcher awards (along with $73,331).

Google has not yet issued a technical fix for the flaw, nor a timeline for when it might — and it’s not clear if Google will ever make a technical change to somehow address this issue. The company has, however, updated its documentation to tell cloud providers to use the sub-identifier. Google also offers instructions to founders on how companies should properly shut down Google Workspace and prevent the problem.

Ultimately, Google says, the fix is for founders shuttering a company to make sure they properly close all of their cloud services. “We appreciate Dylan Ayrey’s help identifying the risks stemming from customers forgetting to delete third-party SaaS services as part of turning down their operation,” the spokesperson said.

Ayrey, a founder himself, understands why many founders might not have ensured their cloud services were disabled. Shuttering a company is actually a complicated process done during what could be an emotionally painful time — involving many items, from disposing of employee computers, to closing bank accounts, to paying taxes.

“When the founder has to deal with shutting the company down, they’re probably not in a great head space to be able to think about all the things they need to be thinking about,” Ayrey says.