I realize that this is a controversial consideration, for many reasons, and that it will likely never gain traction, and maybe it shouldn’t. But maybe there are benefits to implementing more stringent controls over social media algorithms, and limitations on what can and can’t be boosted by them, in order to address the constant amplification of rage-baiting, which is clearly causing massive divides in Western society.

The U.S., of course, is the prime example of this, with extremist social media personalities now driving massive divides in society. Such commentators are effectively incentivized by algorithmic distribution; Social media algorithms aim to drive more engagement, in order to keep people using their respective apps more often, and the biggest drivers of engagement are posts that spark strong emotional response.

Various studies have shown that the emotions that drive the strongest response, particularly in terms of social media comments, are anger, fear and joy. Though of the three, anger has the most viral potential.

“Anger is more contagious than joy, indicating that it can drive more angry follow-up tweets and anger prefers weaker ties than joy for the dissemination in social network, indicating that it can penetrate different communities and break local traps by more sharing between strangers.”

So anger is more likely to spread to other communities, which is why algorithmic incentive is such a major concern in this respect, because algorithmic equations, which are not able to factor in human emotion, will amplify whatever’s driving the biggest response, and show that to more users. The system doesn’t know what it’s boosting, all it’s assessing is response, with the binary logic being that if a lot of people are talking about this subject/issue/post, then maybe more people will be interested in seeing the same, and adding their own thoughts as well.

This is a major issue with the current digital media landscape, that algorithmic amplification, by design, drives more angst and division, because that’s inadvertently what it’s designed to do. And while social platforms are now trying to add in a level of human input into this process, in approaches like Community Notes, which append human-curated contextual pointers to such trends, that won’t do anything to counter the mass-amplification of divisive content, which again, creators and publishers are incentivized to create in order to maximize reach and response.

There’s no way to address such within purely performance-driven algorithmic systems. But what if the algorithms were designed to specifically amplify more positive content, and reduce the reach of less socially beneficial material?

That’s already happening in China, with the Chinese government implementing a level of control over the algorithms in popular local apps, in order to ensure that more positive content is amplified for more people.

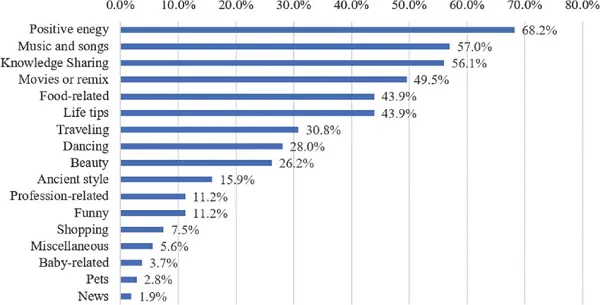

As you can see in this listing of the topics that see the highest rate of promotion on Douyin, which is the Chinese local version of TikTok, among the most popular topics are ‘positive energy’ and ‘knowledge sharing,’ two topics that would be unlikely to get anywhere near these levels of comparative engagement on TikTok.

That’s because the Chinese government seeks to manage what young people are exposed to in social apps, with the idea being that by promoting more positive trends, that’ll inspire the youth to aspire to more beneficial, socially valuable elements.

As opposed to TikTok, in which prank videos, and increasingly, content promoting political discourse, are the norm. And with more and more people now getting their news inputs from TikTok, especially younger audiences, that means that the divisive nature of algorithmic amplification is already impacting youngsters, and their perspectives on how the world works. Or more operatively, how it doesn’t under the current system.

Some have even suggested that this is the main aim of TikTok, that the Chinese government is seeking to use TikTok to further destabilize Western society, by seeding anti-social behaviors via TikTok clips. That’s a little too conspiratorial for me, but it is worth noting the comparative division that such amplification inspires, versus promoting more beneficial content.

To be clear, I’m not arguing that Western governments should be ruling social media algorithms in the way that the CCP influences the trends in popular social apps in China. But there is something to be said for chaos versus cohesion, and how social platform algorithms contribute to the confusion that drives such division, particularly among younger audiences.

So what’s the answer? Should the U.S. government look to, say, take ownership of Instagram and assert its own influence over what people see?

Well, given that U.S. President Donald Trump remarked last week that he would make TikTok’s algorithm “100% MAGA” if he could, that’s probably less than ideal. But there does seem to be a case for more control over what trends in social apps, and for weighting certain, more positive movements more heavily, in order to enhance understanding, as opposed to undermining it.

The problem is there’s no arbitrator that anyone can trust to do this. Again, if you trust the sitting government of the time to control such, then they’re likely to angle these trends to their own benefit, while such an approach would also require variable approaches in each region, which would be increasingly difficult to manage and trust.

You could look to let broad governing bodies, like the European Union, manage such on a broader scale, though EU regulators have already caused significant disruption through their evolving big tech regulations, for questionable benefit. Would they be any better at managing positive and negative trends in social apps?

And of course, all of this is implementing a level of bias, which many people have been opposing for years. Elon Musk ostensibly purchased Twitter for this exact reason, to stop the Liberal bias in social media apps. And while he’s since tilted the balance the other way, the Twitter/X example is a clear demonstration of how private ownership can’t be trusted to get this right, one way or the other.

So how do you fix it? Clearly, there’s a level of division within Western society which is leading to major negative repercussions, and a lot of that is being driven by the ongoing demonization of groups of people online.

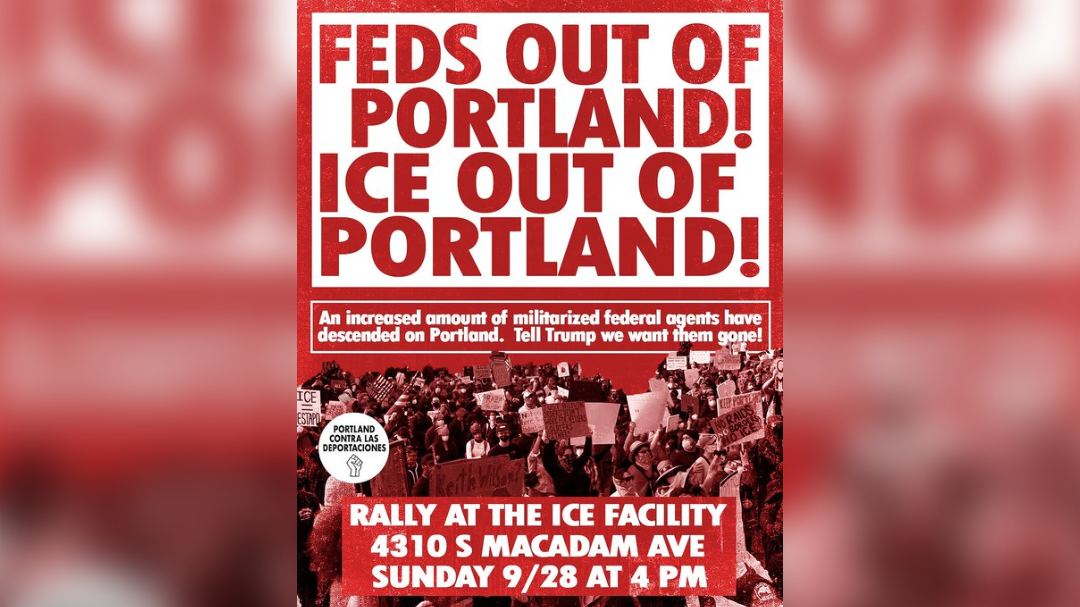

As an example of this in practice, I’m sure that everybody knows at least one person who posts about their dislike for minority groups online, yet that same person probably also knows people in their real life who are part of those same groups that they vilify, and they have no problem with them at all.

That disconnect is the issue, that who people are in real life is not who they portray online, and that broad generalization in this way is not indicative of the actual human experience. Yet algorithmic incentives push people to be somebody else, driven by the dopamine hits that they get from likes and comments, inflaming sore spots of division for the benefit of the platforms themselves.

Maybe, then, algorithms be eliminated entirely. That could be a partial solution, though the same emotional incentives also drive sharing behaviors. So while removing algorithmic amplification could reduce the power of engagement-driven systems, people would still be incentivized, to a lesser degree, to boost more emotionally-charged narratives and perspectives.

You would still, for example, see people sharing clips from Alex Jones in which he deliberately says controversial things. But maybe, without the algorithmic boosting of such, that would have an impact.

People these days are also much more technically savvy overall, and would be able to navigate online spaces without algorithmic supports. But then again, platforms like TikTok, which are entirely driven by signals that are defined by your viewing behavior, have changed the paradigm for how social platforms work, with users now much more attuned to letting the system show them what they want to see, as opposed to having to seek it out for themselves.

Removing algorithms would also see the platforms suffer massive drops in engagement, and thus, ad revenue as a result. Which could be a bigger issue in terms of restricting trade, and social platforms now also have their own armies of lobbyists in Washington to oppose any such proposal.

So if social platforms, or some higher arbitrator, cannot interfere, and downgrade certain topics, while boosting others, in the mould of the CCP approach, there doesn’t seem to be an answer. Which means that the heightened sense of emotional response to every issue that comes up is set to drive social discourse into the future.

That probably means that the current state of division is the norm, because with a general public that increasingly relies on social media to keep it informed, they are also going to keep being manipulated by such, based on the foundational algorithmic incentives.

Without a level of intervention, there’s no way around this, and given the opposition to even the suggestion of such interference, as well as the lack of answers on how it might be applied, you can expect to keep being angered by the latest news.

Because that emotion that you feel when you read each headline and hot take is the whole point.