The Pentagon has a problem: How does one of the world’s largest employers avoid doing business with companies that rely on China’s Huawei Technologies Co., the world’s largest telecommunications provider?

So far, the Defense Department is saying that it can’t, despite a 2019 US law that barred it from contracting with anyone who uses Huawei equipment. The Pentagon’s push for an exemption is provoking a fresh showdown with Congress that defense officials warn could jeopardize national security if not resolved.

As it has done since the law was passed more than five years ago, the Pentagon is seeking a formal waiver to its obligations under Section 889 of the 2019 National Defense Authorization Act, which barred government agencies from signing contracts with entities that use Huawei components.

Its rationale is that Huawei is so firmly entrenched in the systems of countries where it does business — the company accounts for almost one-third of all telecommunications equipment revenue globally — that finding alternatives would be impossible. Meeting the restrictions to the letter would disrupt the Pentagon’s ability to purchase the vast quantities of medical supplies, drugs, clothing and other types of logistical support the military relies on, officials contend.

“There are certain parts of the world where you literally cannot get away from Huawei,” said Brennan Grignon, the founder of 5M Strategies and a former Defense Department official. “The original legislation had very good intentions behind it, but the execution and understanding of the implications of what it would mean, I personally think that wasn’t really thought through,” she said.

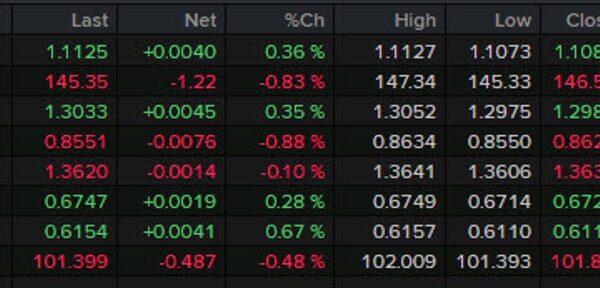

So far, the House and Senate committees in charge of the legislation have declined to include a waiver in the 2025 National Defense Authorization Act. That’s a reflection of growing anti-China sentiment and a frustration that Huawei, whose profit surged 564% in the most recent quarter, has managed to deflect the impact of US financial sanctions imposed on the company.

Representatives for the House and Senate Armed Services Committees did not respond to requests for comment.

The move to target Huawei hearkens back to the US push that began in earnest under President Donald Trump to get tough on China and companies like Huawei that American officials say could be used as a spying tool by the Chinese government.

That push has mirrored a broader US effort to persuade governments to rid Huawei from their most sensitive networks. A refusal by the United Arab Emirates to rip out all Huawei hardware from its tech networks scuttled a deal for the Gulf nation to buy F-35 fighter jets. The US has made similar requests to Saudi Arabia and some Latin American nations.

In some cases, countries have objected, arguing that the US and its allies have no alternative to Huawei’s products, which are often much less expensive than those offered by competitors.

‘They’re Lazy’

The Pentagon argument doesn’t hold sway with some China hawks, who argue that the Defense Department must move more quickly and use its sway as a major buyer to force change.

“I do have some sympathy with the Pentagon guys because they do have a huge network of different things that they have to connect with in the Asia-Pacific region and also in Europe,” said Clyde Prestowitz, president of the Economic Strategy Institute. “But they’re lazy. For companies in those areas, to have big business with the US Department of the Defense is important. And I feel that we should be taking every step to eliminate Huawei where we can.”

Yet in an analysis released in April, the Pentagon maintained that granting the waiver authority “would enable vital resupply missions in the Indo-Pacific, European and African theaters.”

In many parts of the world, US military personnel depend on Huawei networks to do their jobs, from special operators carrying out missions in Africa to senior Pentagon officials attending international air shows in Paris and Farnborough, outside of London.

Pentagon spokesman Jeff Jurgensen said extending the waiver would allow for purchases if they’re deemed to further US national security interests. The waiver wouldn’t extend to elements of the intelligence community, he said.

Senator Mark Warner, chairman of the chamber’s intelligence committee, acknowledged a waiver may be necessary. But he declined to say when or if that might happen.

“I understand the need for 889 waivers in limited contexts where it’s in the larger national security interest of the United States,” Warner, a Virginia Democrat, said in a statement.