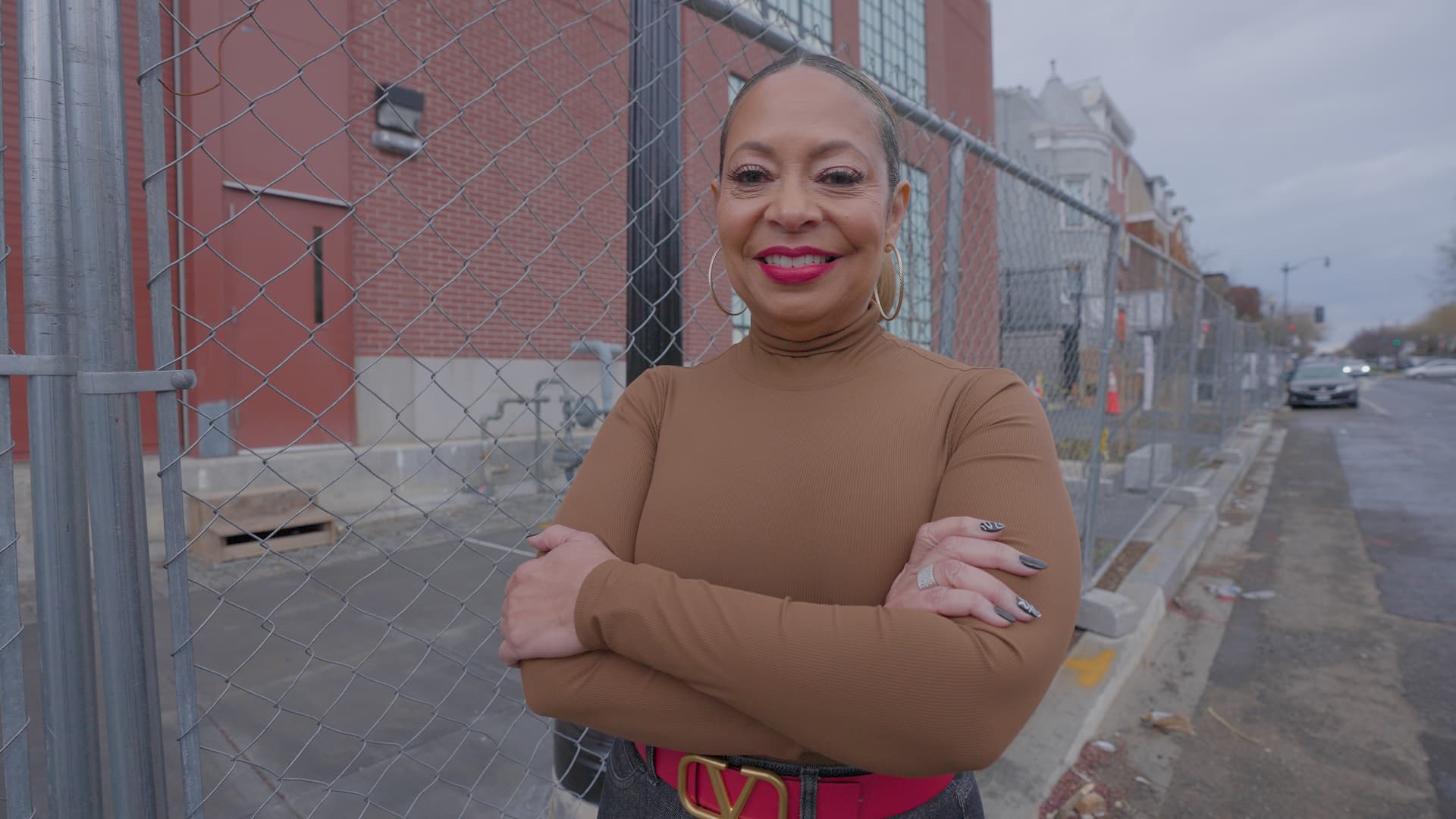

Deryl McKissack’s profession is a fruits of effort from 5 generations.

The 62-year-old is the president and CEO of McKissack & McKissack, the Washington, D.C.-based building administration and design agency behind a few of at present’s most recognizable buildings — from constructing the Smithsonian African American Museum of Historical past and Tradition to repairing the Abraham Lincoln and Thomas Jefferson memorials.

The agency’s legacy dates again to her great-great grandfather Moses, a talented brick maker who initially got here to the U.S. as a slave in 1790. His abilities have been handed down and cultivated from technology to technology, prompting two of his grandsons to create a building firm in Tennessee, additionally known as McKissack & McKissack.

That firm stays within the household, now based mostly in New York and run by McKissack’s twin sister Cheryl. “My father always took us [to] job sites, took us to the office. We talked about it around the table,” says McKissack. “It was always a very integral part of our family.”

Motivated by a need to strike out on her personal, and to see extra Black girls CEOs within the building business, McKissack withdrew $1,000 from her financial savings account and launched her firm in 1990. Immediately, it brings in between $25 million and $30 million per 12 months, in accordance with paperwork reviewed by CNBC Make It, and manages $15 billion in tasks with workplaces in Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles and Baltimore.

“I remember in college, there were probably three women in my class, and my twin sister was one of them. So it’s very rare that women are in this industry, but we’re excelling,” McKissack says.

‘I had this burning ardour … that I simply had to do that’

McKissack left an engineering job with a six-figure wage to launch her firm, and rapidly discovered that even with a Howard College civil engineering diploma and related work expertise, attracting shoppers was tough.

Lugging an previous projector round, she introduced slides of labor she’d achieved for relations to assist “sell my wares.” She positioned a job advert within the Washington Put up, and employed an worker.

“It was touch and go because I didn’t have a bank that believed in me,” says McKissack. “It took me five years to get my first $10,000 line of credit. I probably went to 11 banks that told me ‘no’ … [but] I had this burning passion on the inside that I just had to do this, and it was going to work out for me.”

An illustration of Moses McKissack, who got here to the U.S. as a slave and have become a grasp builder and brickmaker.

Deryl McKissack

She used her networking abilities to land her firm’s first undertaking: doing inside work at her alma mater. She and her lone worker did all of the work themselves, with McKissack placing in 80 hours of labor per week, she says.

One profitable job led to a different, and McKissack constructed a portfolio of labor to point out potential shoppers. She utilized for jobs as a federal contractor, getting her foot within the door to work on building tasks on the White Home and U.S. Treasury constructing. Bigger federal tasks adopted.

McKissack solely paid herself $7,200 her first 12 months in enterprise, she says. Her second, $18,000. She lastly paid herself a $100,000 wage after roughly ten years, she provides, prioritizing paying her workers over herself alongside the best way.

“I’m extremely proud of where we are and the projects that we’ve done … the impact that we’ve had in people’s lives,” says McKissack.

‘I have never made it till extra Black [people] have made it’

The worldwide building business is projected to be price $13.9 trillion by 2037, in accordance with a 2023 report from market analysis agency Oxford Economics. But girls nonetheless make up only 1.4% of construction CEOs worldwide, and Black girls account for a fraction of that.

Regardless of the an identical firm names, McKissack and her sister do run separate companies — however they’ve collaborated on a number of tasks, and infrequently “trade notes” with one another, she says.

“We lean on each other in challenging times. And it’s great to have an identical twin that is doing the same thing that I’m doing in a bigger city like New York,” she says. “The challenges that she faces are different from mine, but they’re similar. So it’s good to have someone to talk to.”

McKissack sisters Andrea, Cheryl and Deryl with their father, William DeBerry.

Deryl McKissack

A wholesome assist system is uncommon for many Black and girls building executives, largely as a result of so few of them exist, McKissack says. Final 12 months, she based AEC Unites, a nonprofit that gives skilled alternatives for Black expertise within the structure, engineering and building business.

“I haven’t made it until more Blacks and more women have made it,” she says, including: “Once more people that look like me are in the industry and they’re dominating in parts of this industry, then I can sit back and say, ‘We’ve made it.'”

Considered one of them, she hopes, will probably be her daughter — a bioengineering scholar at New York College who might turn out to be the sixth technology of McKissacks within the building business.

“I tell her all the time that all roads lead to McKissack,” she says. “And I don’t care how she gets there.”

Need to make extra cash outdoors of your day job? Join CNBC’s new online course How to Earn Passive Income Online to find out about frequent passive earnings streams, tricks to get began and real-life success tales. Register at present and save 50% with low cost code EARLYBIRD.

Plus, sign up for CNBC Make It’s newsletter to get suggestions and tips for achievement at work, with cash and in life.