President Donald Trump appears to have upended an 85-year relationship between American farmers and the United States’ global exercise of power. But that link has been fraying since the end of the Cold War, and Trump’s moves are just another big step.

During World War II, the U.S. government tied agriculture to foreign policy by using taxpayer dollars to buy food from American farmers and send it to hungry allies abroad. This agricultural diplomacy continued into the Cold War through programs such as the Marshall Plan to rebuild European agriculture, Food for Peace to send surplus U.S. food to hungry allies, and the U.S. Agency for International Development, which aimed to make food aid and agricultural development permanent components of U.S. foreign policy.

During that period, the United States also participated in multinational partnerships to set global production goals and trade guidelines to promote the international movement of food – including the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization, the International Wheat Agreement and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

When U.S. farmers faced labor shortfalls, the federal government created guest-worker programs that provided critical hands in the fields, most often from Mexico and the Caribbean.

At the end of World War II, the U.S. government recognized that farmers could not just rely on domestic agricultural subsidies, including production limits, price supports and crop insurance, for prosperity. American farmers’ well-being instead depended on the rest of the world.

Since returning to office in January 2025, Trump has dismantled the U.S. Agency for International Development. His administration has also aggressively detained and deported suspected noncitizens living and working in the U.S., including farmworkers. And he has imposed tariffs that caused U.S. trading partners to retaliate, slashing international demand for U.S. agricultural products.

Trump’s actions follow diplomatic and agricultural transformations that I research, and which began with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Feed the world, save the farm

Even before the nation’s founding, farmers in what would become the United States staked their livelihood on international networks of labor, plants and animals, and trade.

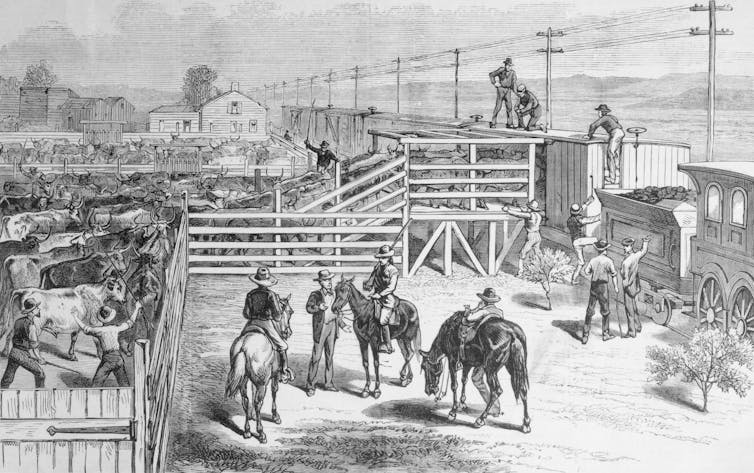

Cotton was the most prominent early example of these relationships, and by the 19th century wheat farmers depended on expanding transportation networks to move their goods within the country and overseas.

But fears that international trade could create economic uncertainty limited American farmers’ interest in overseas markets. The Great Depression in the 1930s reinforced skepticism of international markets, which many farmers and policymakers saw as the principal cause of the economic downturn.

World War II forced them to change their view. The Lend-Lease Act, passed in March 1941, aimed to keep the United States out of the war by providing supplies, weapons and equipment to Britain and its allies. Importantly for farmers, the act created a surge in demand for food.

And after Congress declared war in December 1941, the need to feed U.S. and allied troops abroad pushed demand for farm products ever higher. Food took on a significance beyond satisfying a wartime need: The Soviet Union, for example, made special requests for butter. U.S. soldiers wrote about the special bond created by seeing milk and eggs from a hometown dairy, and Europeans who received food under the Lend-Lease Act embraced large cans of condensed milk with sky-blue labels as if they were talismans.

Another war ends

But despite their critical contribution to the war, American farmers worried that the familiar pattern of postwar recession would repeat once Germany and Japan had surrendered.

Congress fulfilled farmers’ fears of an economic collapse by sharply reducing its food purchases as soon as the war ended in the summer of 1945. In 1946, Congress responded weakly to mounting overseas food needs.

More action waited until 1948, when Congress recognized communism’s growing appeal in Europe amid an underfunded postwar reconstruction effort. The Marshall Plan’s more robust promise of food and other resources was intended to counter Soviet influence.

Sending American food overseas through postwar rehabilitation and development programs caused farm revenue to surge. It proved that foreign markets could create prosperity for American farmers, while food and agriculture’s importance to postwar reconstruction in Europe and Asia cemented their importance in U.S. foreign policy.

Farmers in the modern world

Farmers’ contribution to the Cold War shored up their cultural and political importance in a rapidly industrializing and urbanizing United States. The Midwestern farm became an aspirational symbol used by the State Department to encourage European refugees to emigrate to the U.S. after World War II.

American farmers volunteered to be amateur diplomats, sharing methods and technologies with their agricultural counterparts around the world.

By the 1950s, delegations of Soviet officials were traveling to the Midwest, including Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev’s excursion to Iowa in 1959. U.S. farmers reciprocated with tours of the Soviet Union. Young Americans who had grown up on farms moved abroad to live with host families, working their properties and informally sharing U.S. agricultural methods. Certain that their land and techniques were superior to those of their overseas peers, U.S. farmers felt obligated to share their wisdom with the rest of the world.

The collapse of the Soviet Union undermined the central purpose for the United States’ agricultural diplomacy. But a growing global appetite for meat in the 1990s helped make up some of the difference.

U.S. farmers shifted crops from wheat to corn and soybeans to feed growing numbers of livestock around the world. They used newly available genetically engineered seeds that promised unprecedented yields.

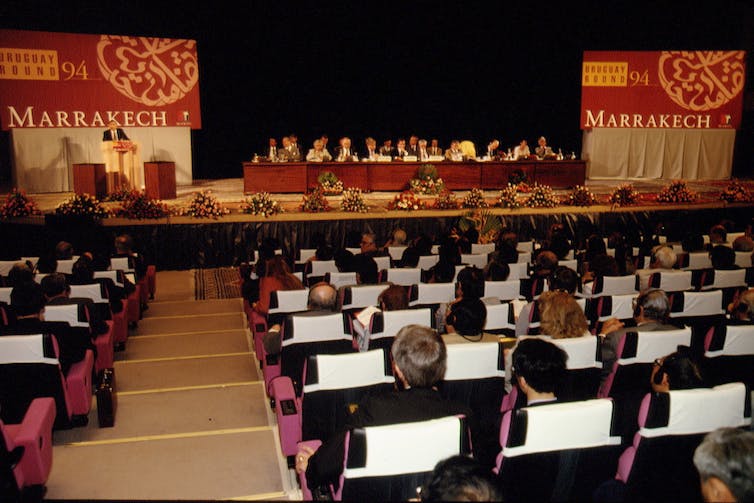

Expecting these transformations to financially benefit American farmers and seeing little need to preserve Cold War-era international cooperation, the U.S. government changed its trade policy from collaborating on global trade to making it more of a competition.

The George H.W. Bush and Clinton administrations crafted the North American Free Trade Agreement and the World Trade Organization to replace the general agreement on trade and tariffs. They assumed American farmers’ past preeminence would continue to increase farm revenues even as global economic forces shifted.

But U.S. farmers have faced higher costs for seeds and fertilizer, as well as new international competitors such as Brazil. With a diminished competitive advantage and the loss of the Cold War’s cooperative infrastructure, U.S. farmers now face a more volatile global market that will likely require greater government support through subsidies rather than offering prosperity through commerce.

That includes the Trump administration’s December 2025 announcement of a US$12 billion farmer bailout. As Trump’s trade wars continue, they show that the U.S. government is no longer fostering a global agricultural market in which U.S. farmers enjoy a trade advantage or government protection – even if they retain some cultural and political significance in the 21st century.

Peter Simons, Lecturer in History, Hamilton College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

This story was originally featured on Fortune.com