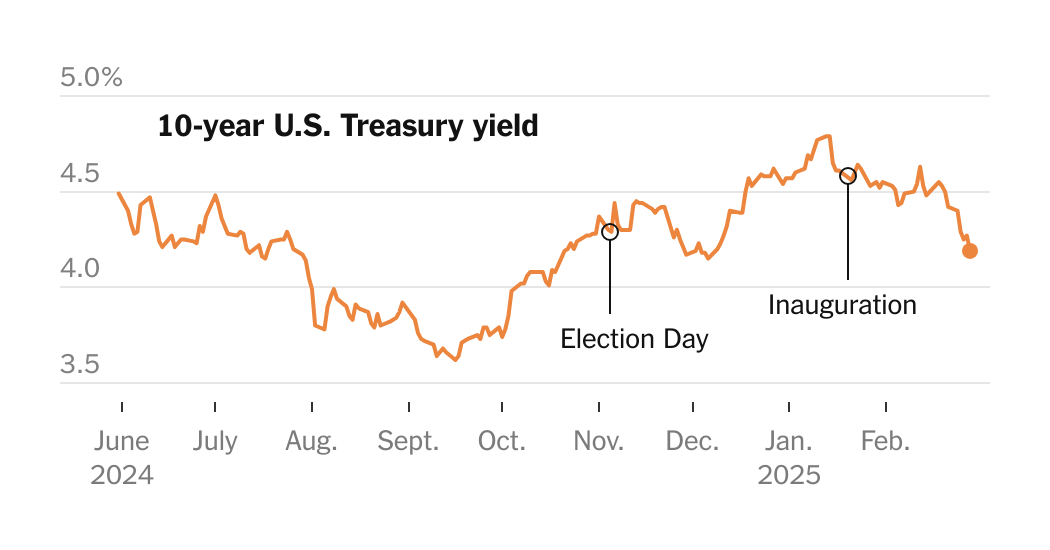

President Trump campaigned on a promise to bring down interest rates. And he has fulfilled that pledge in one key way, with U.S. government bond yields falling sharply.

But the reason for the drop is an unnerving one: Investors appear to be more on edge about the outlook for the economy.

Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has said that the Trump administration considers the 10-year Treasury yield a benchmark of its success in lowering rates. The yield tracks the rate of interest the government pays to borrow from investors over 10 years and has dropped since mid-January, to around 4.2 percent from 4.8 percent. The decline in February was the steepest in several months.

The administration is targeting the 10-year yield because it underpins borrowing costs on mortgages, credit cards, corporate debt and a host of other rates, making it arguably the most important interest rate in the world. As it drops, that should filter through the economy, making many types of debt cheaper.

Unlike the short-term interest rate that is set by the Federal Reserve, the 10-year yield is a market rate, meaning that nobody has direct control over it. Instead, it reflects investors’ views on the economy, inflation, the government’s borrowing needs and changes the Fed may make to its rate in the years ahead.

That’s why the drop in February is troubling, analysts say. It shows, at least in part, that bond investors are growing gloomy about the economic outlook — and quickly.

“The market is pricing a growth scare,” said Blerina Uruci, chief U.S. economist at T. Rowe Price.

A better outcome would be for the declining 10-year yield to reflect slowing inflation, the prospect of more rate cuts by the Fed and a shrinking deficit that would require less government borrowing — all while the economy remains strong.

Instead, inflation expectations have risen this year amid worries that Mr. Trump’s tariff plans, alongside mass deportations, could reignite price increases throughout the economy. Stubborn inflation means the interest rates controlled by the Fed are likely to stay elevated for longer. Some analysts and investors fear that this could weigh on the economy until it cracks and the central bank is pushed into rapidly lowering rates.

Expectations about growth have already begun to sour. On Friday, data from the Commerce Department showed consumer spending falling sharply in January, adding to angst about the economy’s prospects.

The “decidedly downbeat” consumer confidence figures raise questions about whether Mr. Trump’s second term will continue to see a “goldilocks economy” with solid growth and job gains, “or if there is a reckoning in the making,” said Ian Lyngen, an interest rate strategist at BMO Capital Markets.

Mr. Lyngen also highlighted the government’s cost-cutting drive as a factor in the growth worries, should the escalating layoffs of federal government workers spread to other sectors, pushing up unemployment.

“It’s the risk that the official data eventually reflects the upheaval in Washington, D.C.,” he said.

Mr. Bessent, the Treasury secretary, put it differently. Asked about the drop in 10-year yields last week, he sought to credit the Trump administration.

“I’d like to think that some of it’s not luck,” he told Fox Business. “It’s the bond market starting to understand the power of what we are doing here in terms of cutting waste, fraud and abuse in the government.”

Falling rates, whatever the reason for the drop, will help borrowers and tend to support the stock market. But other factors matter too, and if consumers and businesses are worried about the economy, lower rates alone won’t necessarily lead to more spending.

Right now, the Fed is in a holding pattern, signaling that it will keep interest rates steady until it either sees real progress that inflation is in retreat or the labor market weakens significantly.

Benson Durham, head of global policy at Piper Sandler and a former senior staff member at the Fed, said that the central bank may be more inclined to keep rates elevated as inflation concerns remain dominant before eventually responding to lower growth by resuming rate cuts.

Economists fear a situation in which the Fed is forced to keep its short-term rates higher for longer as it seeks to tame inflation, in part because of Mr. Trump’s policies, even if the economy is looking as if it may be about to buckle.

In January, Fed officials argued that a solid economy afforded them time to wait for more concrete evidence that inflation was cooling before cutting rates further.

The central bank will either do “almost nothing” as inflationary pressures persist and the economy remains resilient, said Ajay Rajadhyaksha, global chair of research at Barclays, or cut rates by at least a full percentage point as it races to react to softening growth.

“The U.S. will almost certainly grow at a slower pace in 2025 than 2024,” he said.