Duke Kahanamoku was a real-life American aquaman.

“The Father of Surfing” rode the pipeline of popularity he achieved as an Olympic champion to become the soft-spoken savior of Hawaiian heritage foretold in a king’s deathbed prophecy.

“The ocean is my temple, the waves my prayers,” Kahanamoku reportedly said, one of many quotes that have helped give surfing its spirit of oneness with the water.

“Every wave is a chance to be reborn.”

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO CREATED HIGHWAY REST AREAS, ALLAN WILLIAMS, SMALL-TOWN ENGINEER

He is, among other things, the original “Big Kahuna” – American slang of Hawaiian origin for a dominant personality.

Kahanamoku’s legendary exploits began splashing through Hawaii’s aquamarine surf at record-setting speed, powered only by muscular arms and legs.

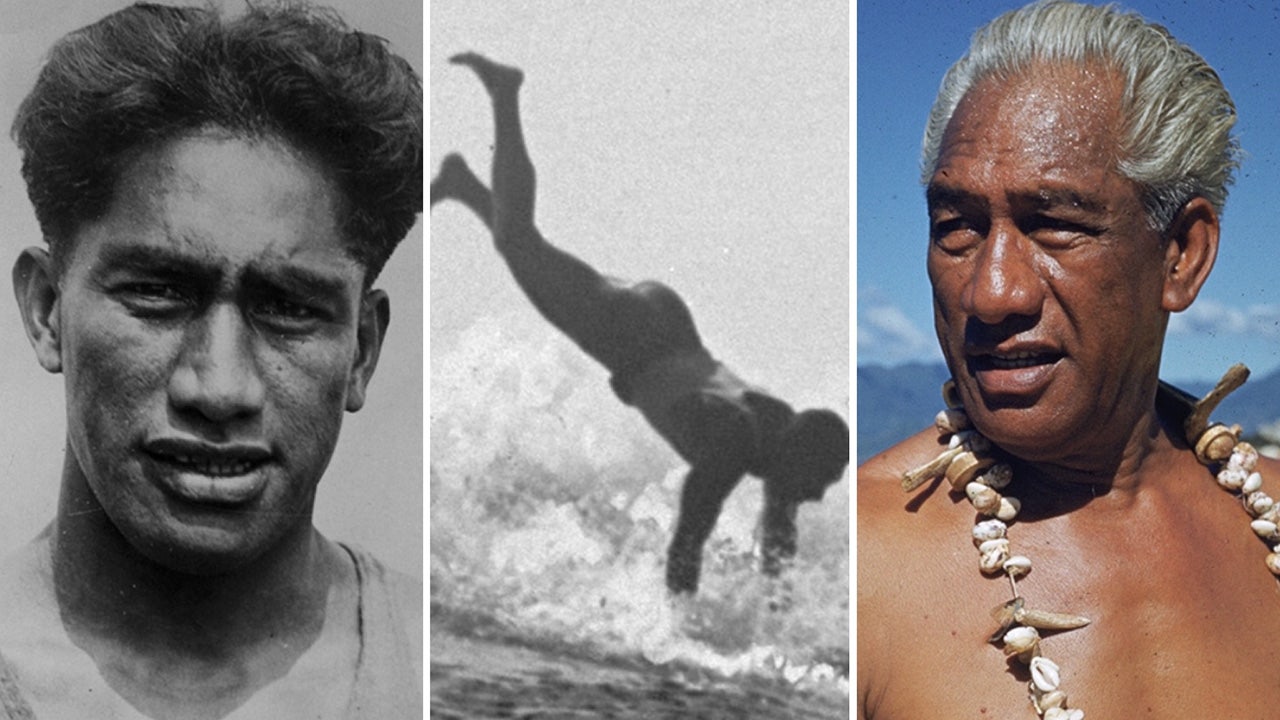

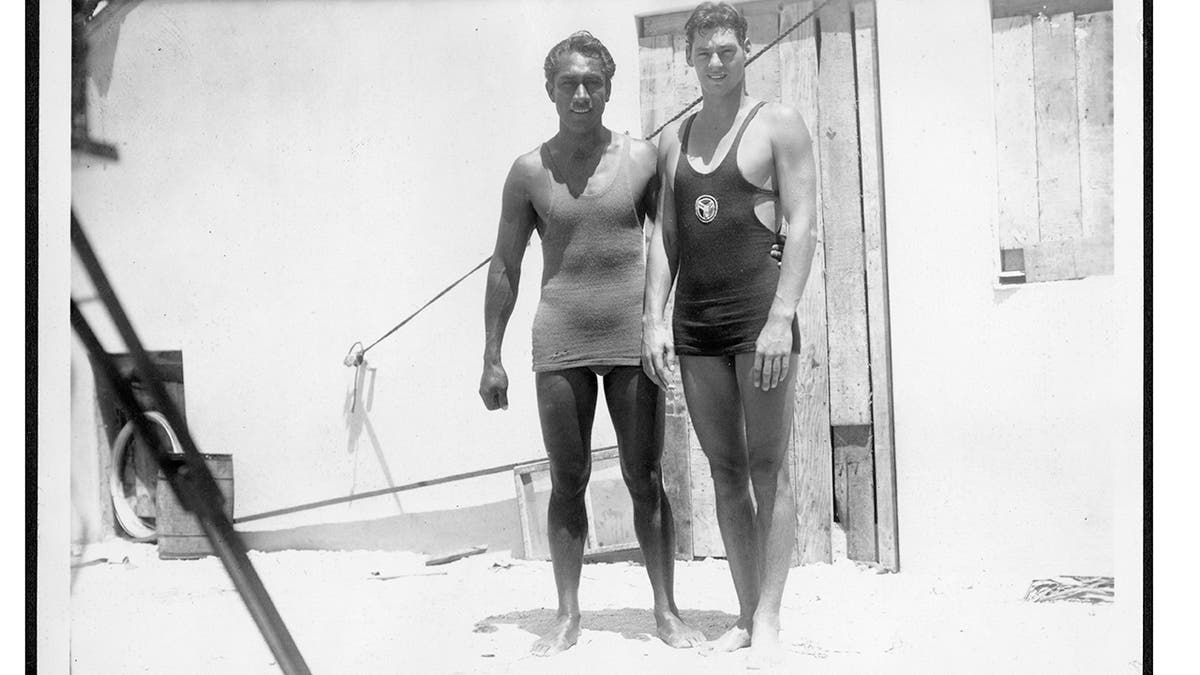

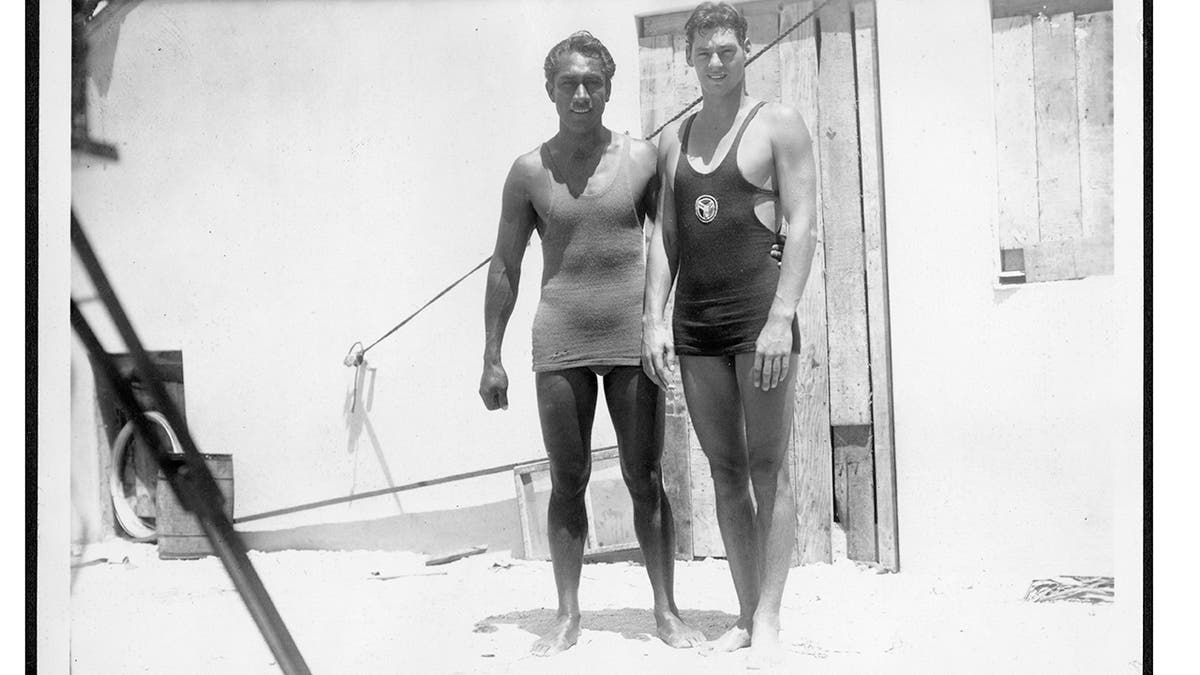

Hawaiian swimming stars Duke Kahanamoku, left, and his younger brother, Sam, at a break during the tryouts at the Olympic Pool in Long Beach, California, for the 1924 Summer Olympics. (Underwood Archives/Getty Images)

He won five Olympic medals – three of them gold – representing the United States before Hawaii was one of them.

The Big Kahuna grew into an international icon in between the Olympics, skimming the surf on his 16-foot, 114-pound, natural-wood longboard with awe-inspiring dexterity.

“To us, he’s the king of surfing.”

Surfing became an Olympic sport for the first time in 2020.

It returns to the Paris games this week. Surfers around the world recognize Duke as royalty.

“To us, he’s the king of surfing,” Kelly Slater, 11-time World Surf League champion, said in the 2022 PBS documentary “Waterman – Duke: Ambassador of Aloha.”

Kahanamoku displayed “superhuman” skills with a legendary rescue at sea, appeared in feature films and spent his twilight years as the state’s official “Ambassador of Aloha.”

Duke Kahanamoku doing one of his stunts with a surfboard at Corona Del Mar, California, while traveling 40 miles per hour on the crest of waves. (NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images)

Kahanamoku was born at a time of tumult in his native society and is, by many accounts, the spirit foretold in a royal prophecy.

“Before they are entirely gone, there will come one in my image who shall have within himself all the glorious strength of a dying race,” Hawaii’s King Kamehameha reportedly announced on his deathbed in 1819.

“He shall be honored throughout the world, and he shall bring fame to my people.”

‘A flutter kick and powerful strokes’

Duke Paoa Kahanamoku was born on Aug. 24, 1890, in Haleʻākala, a landmark home in Honolulu built of pink coral and known for its affiliation with members of Hawaii’s royal family.

Kahanamoku was not among them. Duke was not a title, but his given name. His father, also Duke, was a police officer; his mother, Julia, was described as a faithful Christian.

They had eight other children.

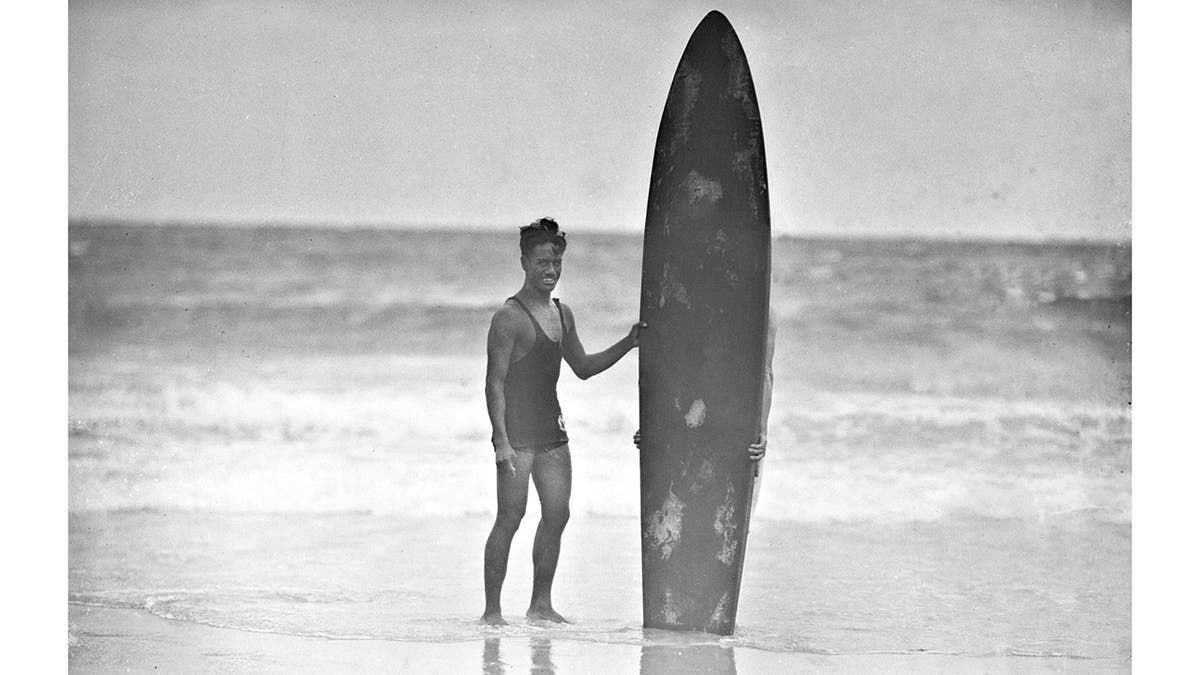

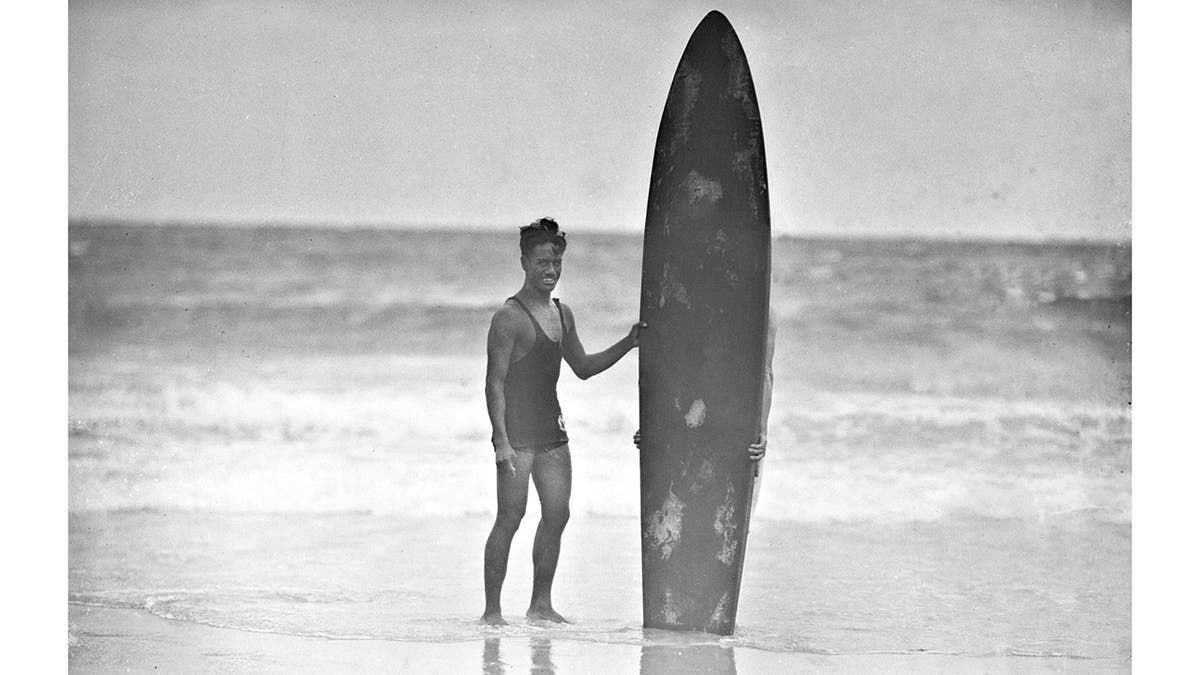

Duke Kahanamoku with his board at a beach in Australia, 1936. (Harry Martin/Fairfax Media via Getty Images)

The family moved to Waikiki, its beach today one of the world’s favorite surfside vacation spots, under the dramatic emerald sparkle of Diamond Head.

Kahanamoku gained national attention in 1911 with a swimming performance that still defies credulity.

A newcomer to official competition, he swam the 100-meter freestyle in the salt water of Honolulu Harbor in 55.4 seconds – shattering the world record by 4.6 seconds.

“AAU officials on the mainland were in disbelief and questioned whether it was a legitimate time,” reports the website of the United States Olympic & Paralympic Museum. “Indeed it was, as they would soon see.”

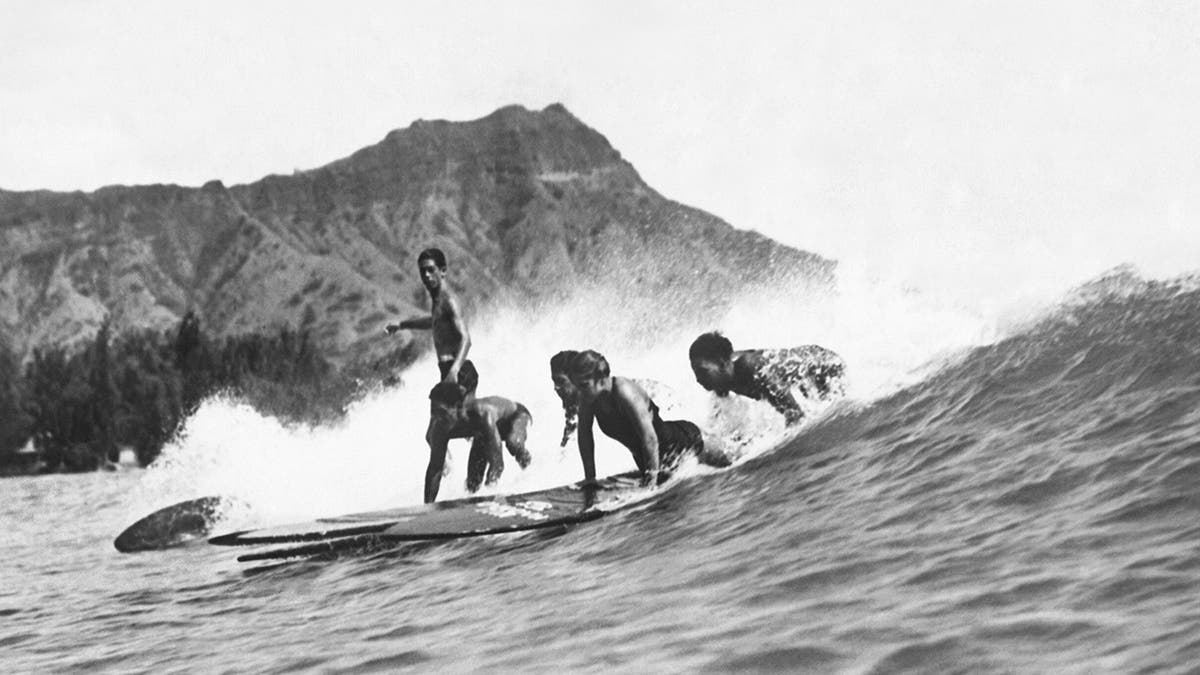

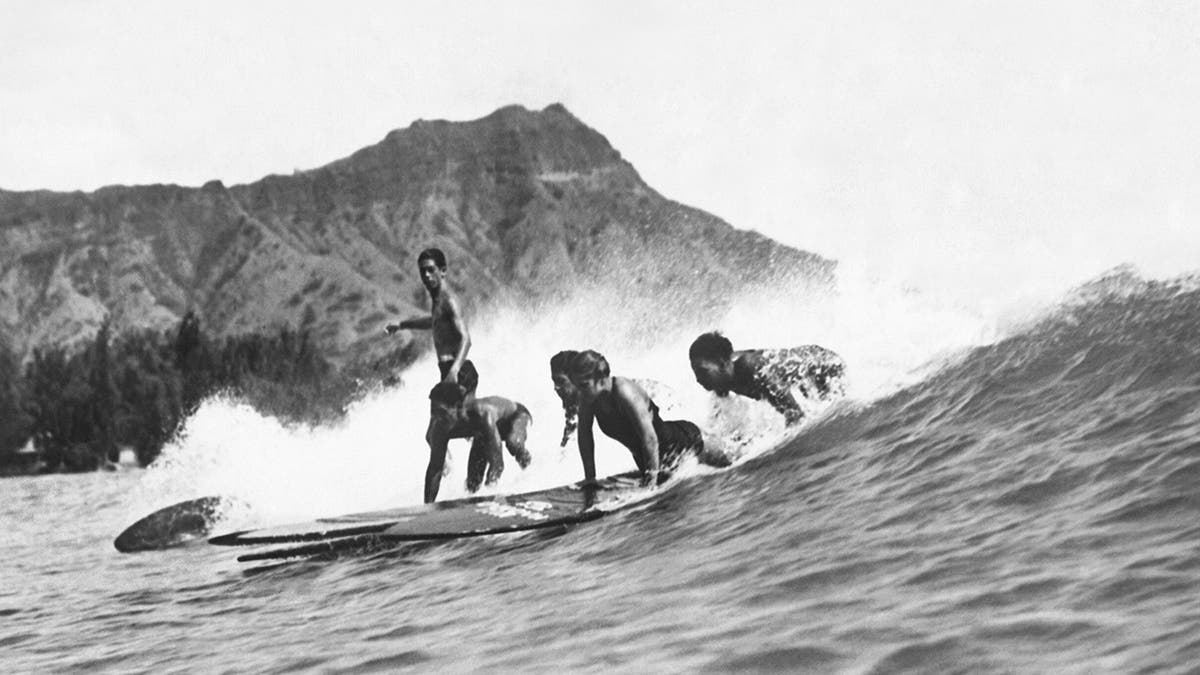

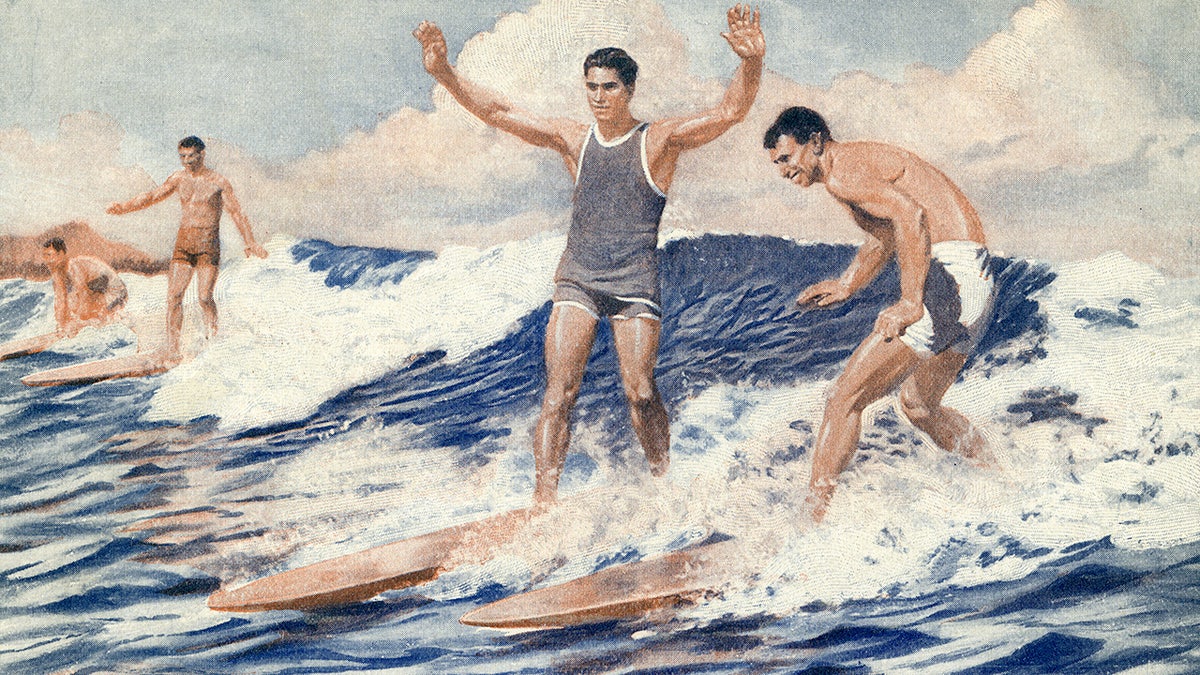

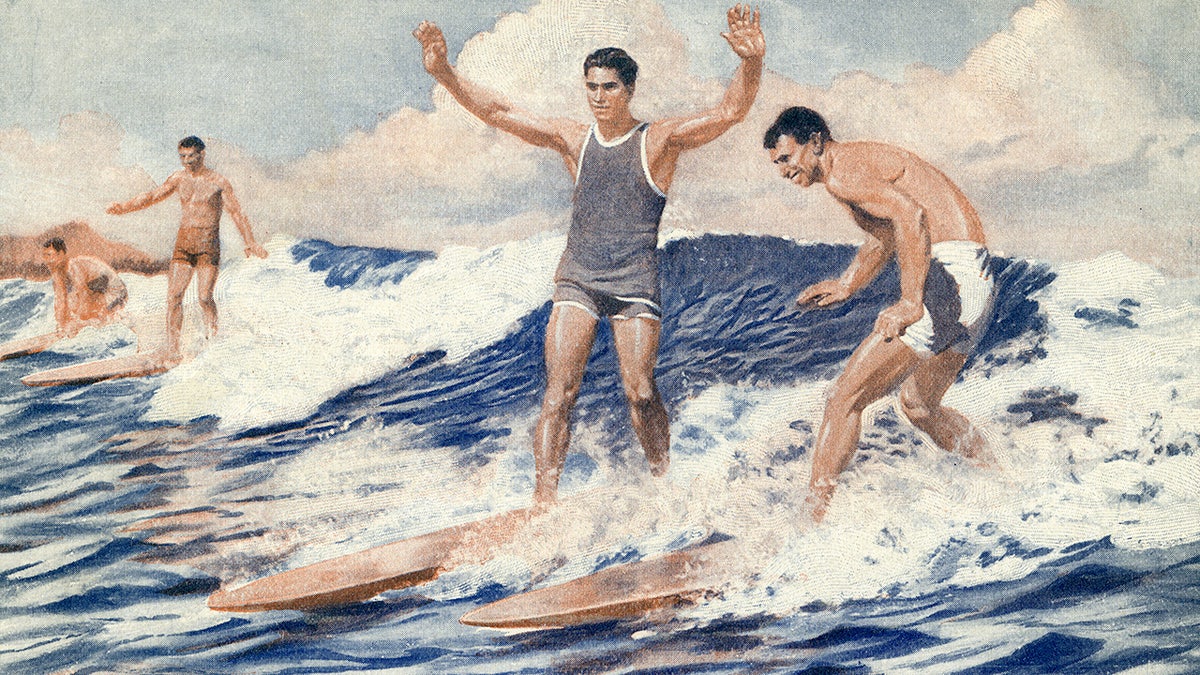

Native Hawaiians riding their surfboards at Waikiki Beach with Diamond Head in the background, Honolulu, Hawaii, circa 1925. (Underwood Archives/Getty Images)

Kahanamoku’s secret was a “a new style of swimming,” the museum writes, “with a flutter kick and powerful strokes.”

The Honolulu boy earned a spot on the U.S. Olympic team at the Stockholm games in 1912. He won his first gold medal in the 100-meter freestyle — adding a silver as part of the men’s 4×200 freestyle relay team.

“AAU officials on the mainland were in disbelief.”

He added two more gold medals in the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp, in the same two events.

Kahanamoku won his final Olympic medal, silver, in 1924 behind fellow American Johnny Weissmuller. The gold medalist became a Hollywood icon, starring in 12 films as Tarzan in the 1930s and 1940s.

Kahanamoku would also become a familiar face on the big screen — but only after kicking up a global sports tsunami with his surfboard.

‘Superhuman rescue’

David Kalakaua, the last king of Hawaii, opened his island paradise empire to the world before dying in 1891, just five months after Kahanamoku was born.

Olympic gold medalists Duke Kahanamoku, left, and Johnny Weissmuller, who later played Tarzan in 12 Hollywood movies, on Waikiki Beach, Honolulu, Hawaii, circa 1927. (PhotoQuest/Getty Images)

Among decisions with an unforeseen impact on world events, the king signed an 1875 treaty to give the United States exclusive use of Pearl Harbor.

MEET THE AMERICAN WHO STITCHED TOGETHER THE STARS & STRIPES, BETSY ROSS, REPUTED WARTIME SEDUCTRESS

Outside influences brought dramatic changes to Hawaiian culture.

“By the end of the 19th century,” reports Surfer Today, “foreign missionaries had almost ‘erased’ surfing, or the act of riding waves, from the Hawaiian Islands.”

Kahanamoku inspired surfing’s revival out of love for the sport and mythical skills.

An advertisement for Valspar Varnish features an illustration of four men surfing the waves at Waikiki, Honolulu, Hawaii, 1922. (Jim Heimann Collection/Getty Images)

Kahanamoku trained for the Olympics on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, surfing in his spare time.

His incredible rides skimming the waves with dolphin-like dexterity became an international sensation – especially Down Under.

“His widely publicized surfing exhibition … lit the fuse to popularize surfing in Australia.”

“His widely publicized surfing exhibition on Jan. 10, 1915, lit the fuse to popularize surfing in Australia,” Eric Middledrop of the Freshwater Surf Life Saving Club, just north of Sydney in New South Wales, told Fox News Digital via email.

“The rest of the world soon followed.”

People who had never seen the ocean followed the Big Kahuna’s surfing exploits 10 years later, during a legendary feat of humanity that generated international headlines.

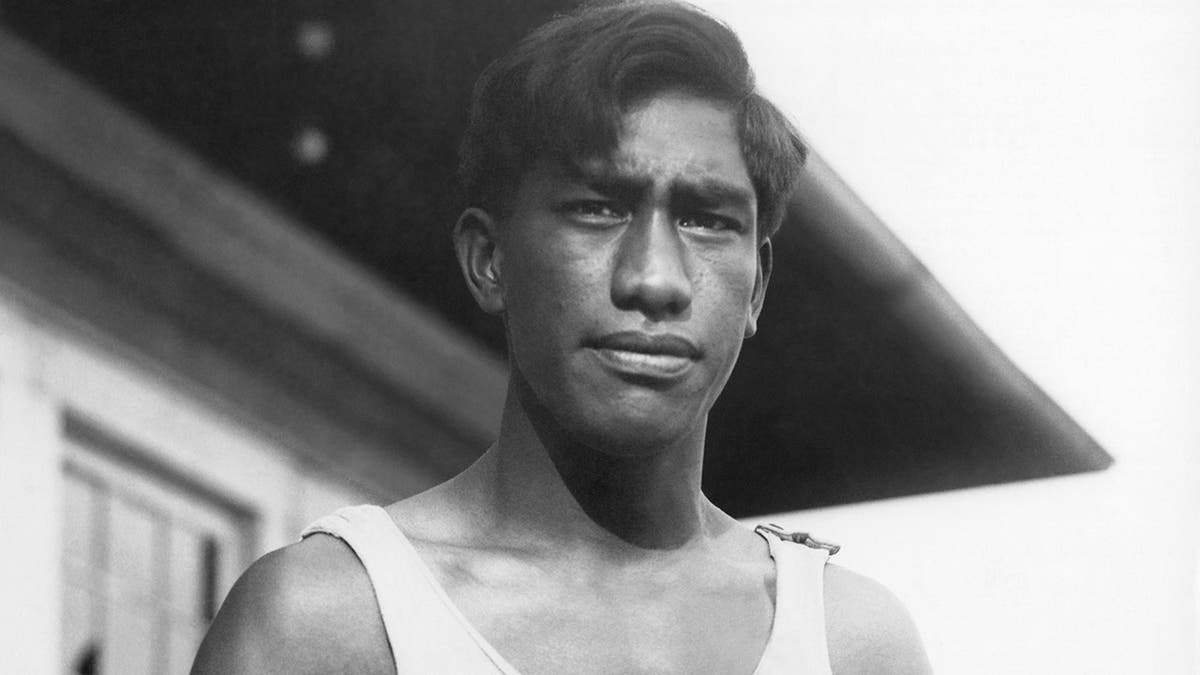

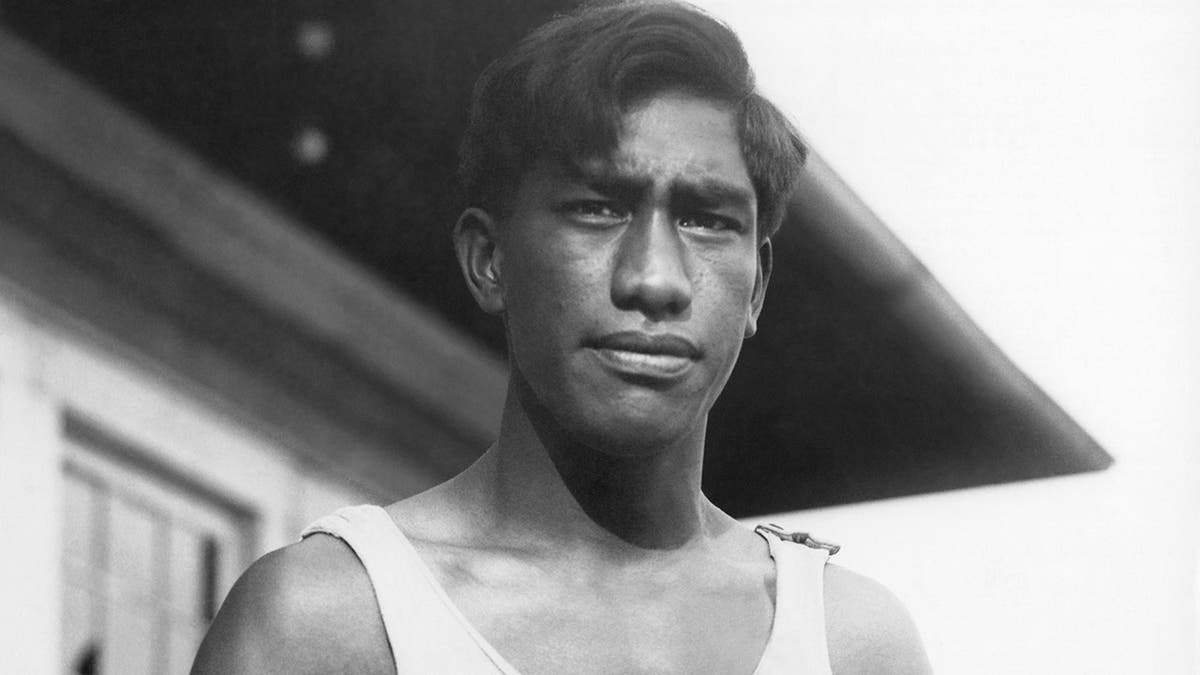

A portrait of swimming and surfing star Duke Kahanamoku, Hawaii, circa 1912. (Underwood Archives/Getty Images)

While surfing at Corona del Mar, California, in 1925, Kahanamoku watched with horror when a 40-foot yacht was swamped by a giant wave.

Seventeen passengers were tossed into the ocean, many badly hurt.

“I reached the screaming and gagging victims and began grabbing at their frantic arms and legs.”

“I reached the screaming and gagging victims and began grabbing at their frantic arms and legs,” Kahanamoku said in contemporary news accounts.

He rescued eight people on four or more trips back and forth to the shore on his board; fellow surfers saved four more.

Franklin D. Roosevelt Jr. and John Roosevelt are pictured with Duke Kahanamoku, center. President Roosevelt, with his sons, made the first visit of a sitting U.S. president to Hawaii in 1934. Kahanamoku gave private surfing lessons to the Roosevelt sons. (Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum/Public Domain)

“Kahanamoku’s performance was the most superhuman rescue act and the finest display of surfboard riding that has ever been seen in the world,” Newport Beach Police Chief Jim Porter told the Los Angeles Times in a period account.

“Many more would have drowned but for the quick work of the Hawaiian swimmer.”

‘Ambassador of Aloha’

Duke Kahanamoku died on Jan. 22, 1968. He was 77 years old and was buried at sea.

The Big Kahuna’s legend only grew in later life.

Duke Kahanamoku playing a Native chief in the 1955 film “Mister Roberts.” Kahanamoku was an Olympic swimming champion before his acting career and went on to serve as Honolulu’s sheriff for 26 years. (Slim Aarons/Getty Images)

He appeared on the big screen in 15 films, including in “Wake of the Red Witch” with another iconic American “Duke,” his friend John Wayne.

Kahanamoku, in his free time, played ukulele, adopted by Polynesian performers from Portuguese sailors, his musicianship forging the instrument’s affiliation with Hawaiian harmonies.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP FOR OUR LIFESTYLE NEWSLETTER

“He was known to spontaneously dance hula,” according to a Facebook account from Duke’s Waikiki, a popular Honolulu watering hole named in honor of the hometown hero.

“His larger-than-life presence helped America proclaim Hawaii as the 50th state, melding two cultures into one United States,” boasts the Discover Hawaii website.

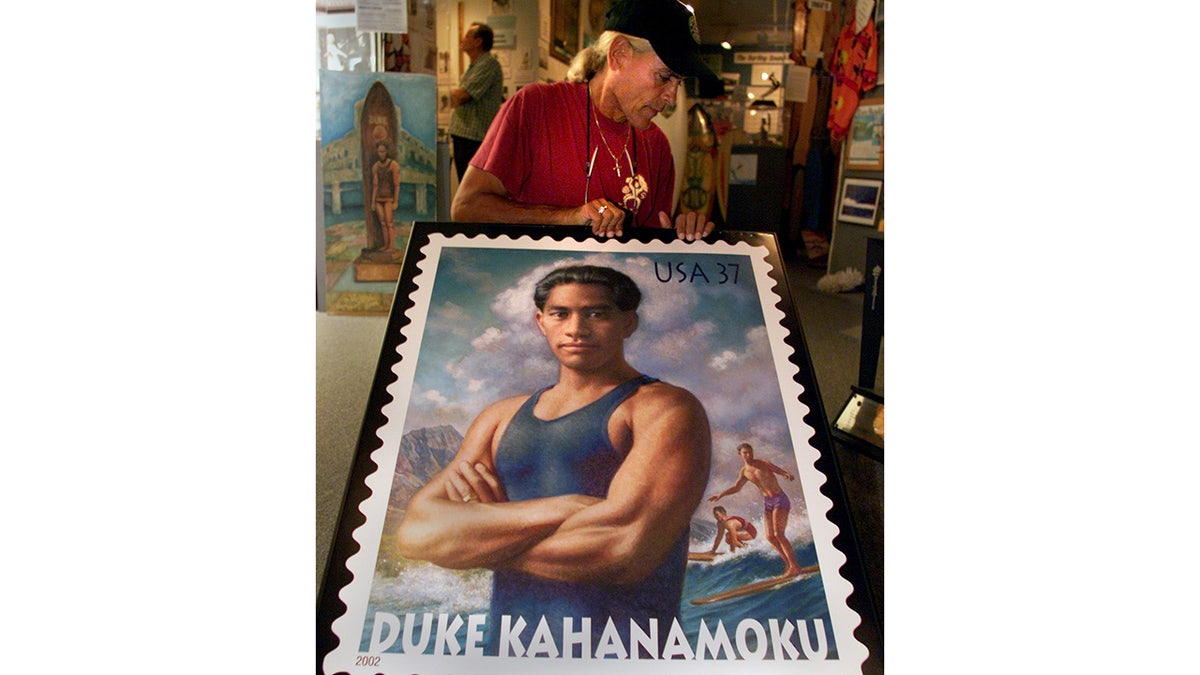

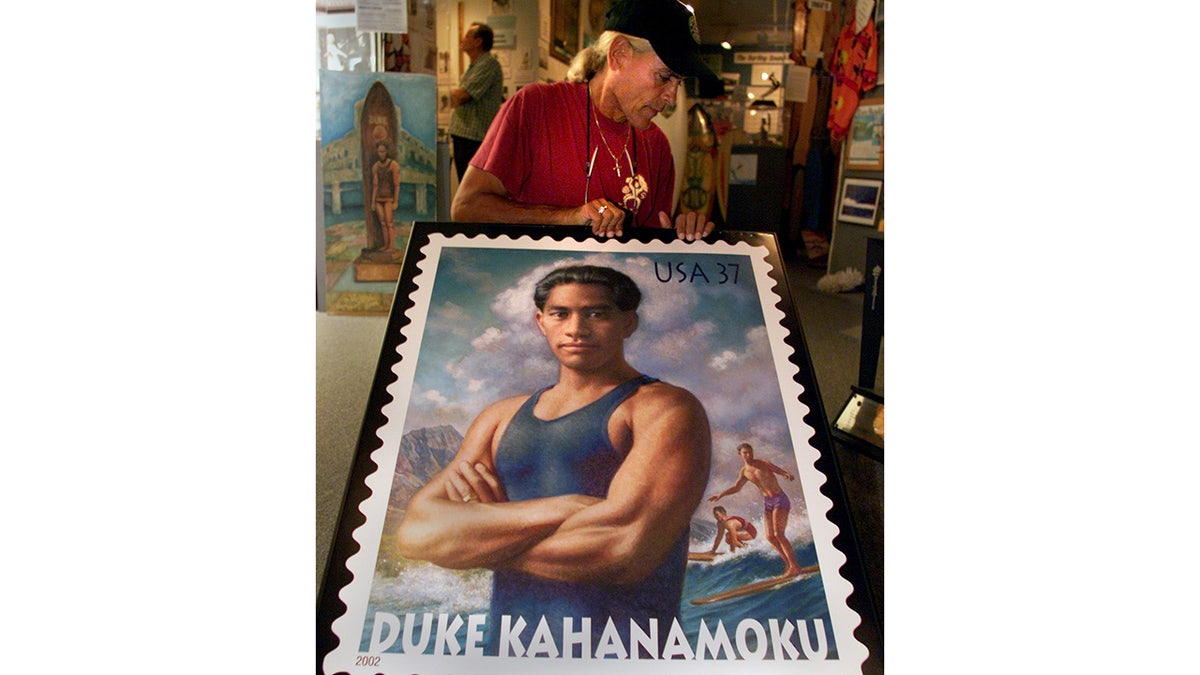

Museum volunteer Cisco Torres hangs a replica picture of a United States postage stamp of surfing legend Duke Kahanamoku at the Huntington Beach International Surfing Museum in California. (Glenn Koenig/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Kahanamoku was named Hawaii’s official global “Ambassador of Aloha” when it joined the Union in 1959, some say fulfilling the prophecy of King Kamehameha:

“He shall be honored throughout the world, and he shall bring fame to my people.”

To read more stories in this unique “Meet the American Who…” series from Fox News Digital, click here.

The Big Kahuna still scans the surf for barrels and bombs around the world. He’s honored with monuments on beaches in California, New Zealand, Australia and Hawaii.

Duke’s statue on Waikiki Beach is both a physical and cultural landmark of Hawaiian tradition.

Duke Kahanamoku Statue at Waikiki Beach in Honolulu, Hawaii. (Prisma Bildagentur/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

The handmade surfboard he used to popularize surfing in Australia is a global treasure of the sport. It even has a human caretaker, much like hockey’s Stanley Cup.

“We believe that this surfboard would probably be the most important piece of surfing memorabilia in Australia, if not the world,” said Middledrop of the Freshwater Surf Lifesaving Club.

The Aussie spokesperson’s digital signature speaks to the reverence for the Big Kahuna in surf culture. Middledrop’s official title is “Duke Kahanamoku Surfboard Caretaker.”

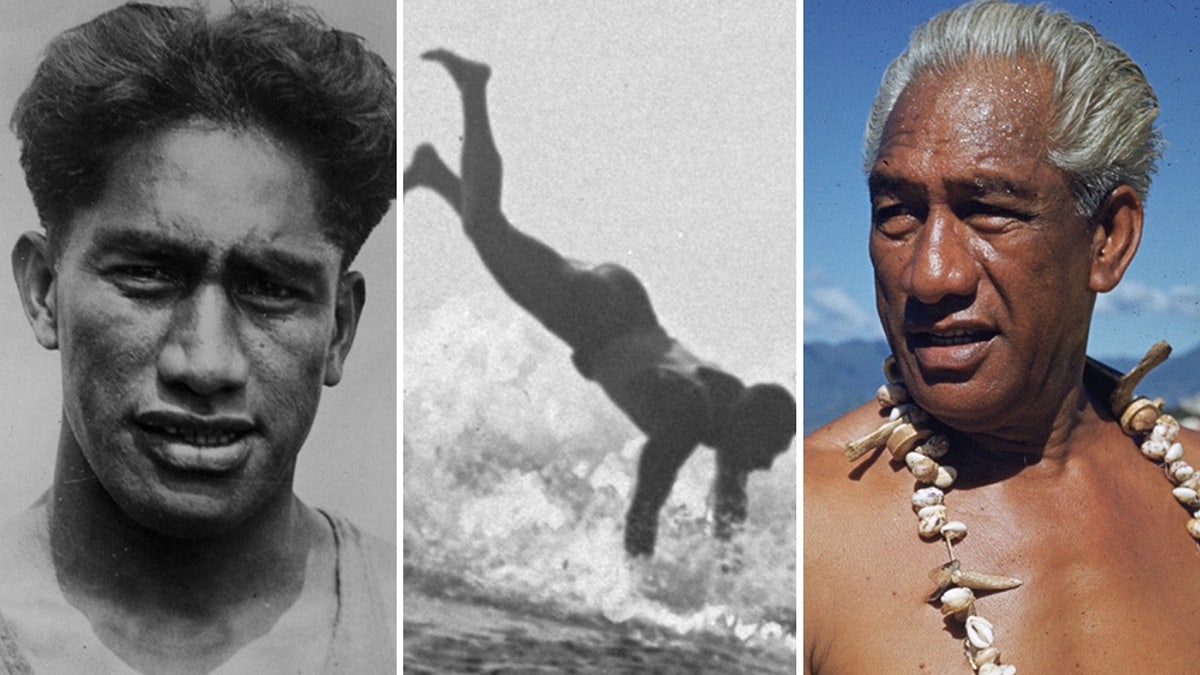

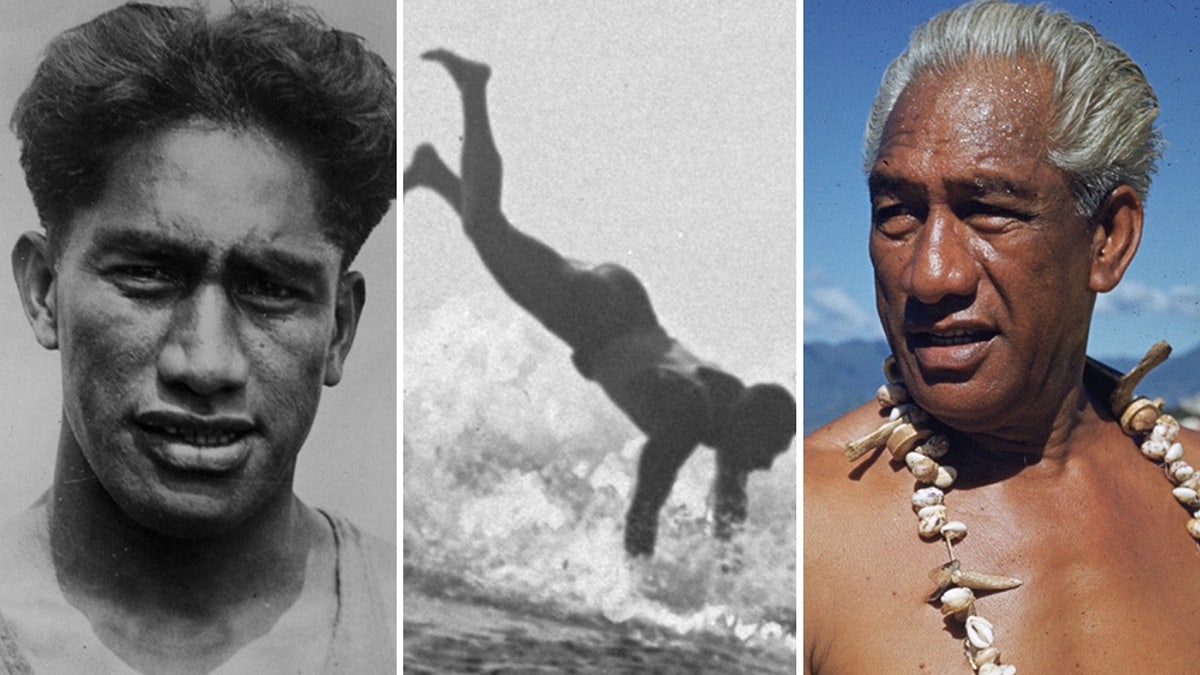

Duke Kahanamoku was a three-time Olympic gold medalist in swimming who popularized surfing around the world. (Hulton Archive/Getty Images; NY Daily News Archive via Getty Images; Slim Aarons/Getty Images)

Kahanamoku enjoyed equal reverence in the PBS “Waterman” documentary.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

“When you come across something that is just so genuine and so good, you can’t help but drop whatever you think you know about people,” said narrator Jason Momoa.

“He changed lives just by being who he was.”