I sometimes quiver at the crunch of the potato chip and convulse at the slurp of the ramen—and please don’t get me started on my Dad savoring his blueberry pie with excruciatingly slow bites.

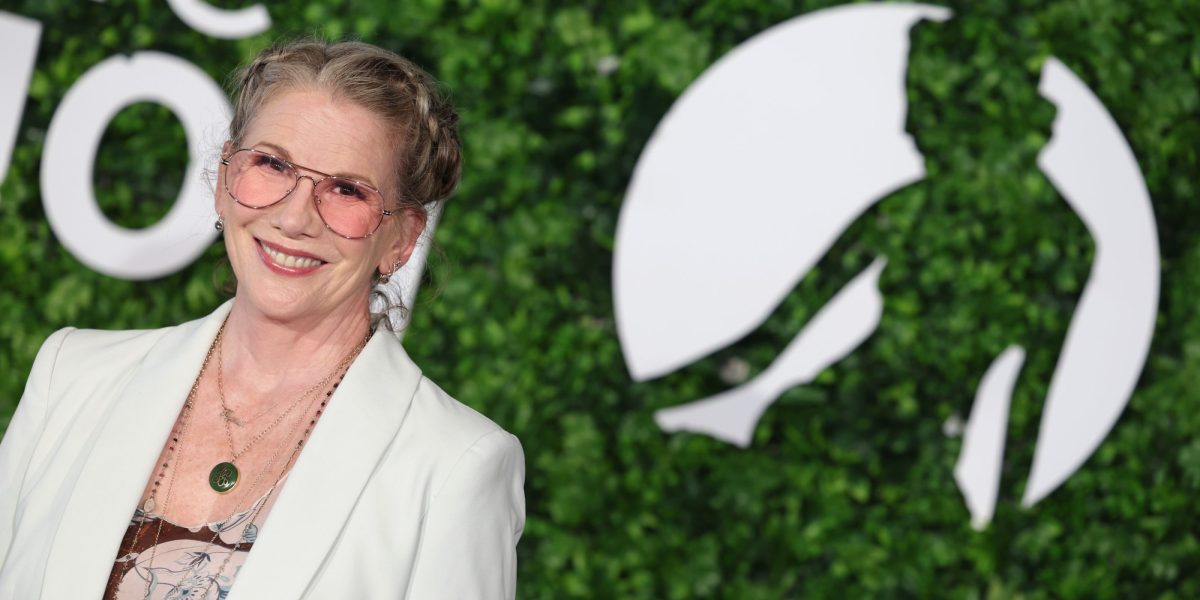

What some may consider everyday noises make me repulsed or even angry. Same with my mom and my sister—and, it turns out, Little House on the Prairie star Melissa Gilbert, who spoke out this week about having misophonia, the neurological disorder we all have, along with an estimated 15% of adults.

“I sobbed when I found out that it had a name and I wasn’t just a bad person,” Gilbert, 60, told People in an exclusive interview this week.

Below, more about the disorder that prompts intense emotional reactions to very specific noises.

What is Misophonia?

People with misophonia, according to the Cleveland Clinic, are triggered, feeling intense and hard-to-control “anger, anxiety, or disgust” when listening to certain sounds—either a couple of specific sounds, such as a person chewing or water dripping from a tap, or a range of noises, from heavy breathing to the click of a pen and the ticks of a clock.

While misophonia doesn’t have official recognition as a disorder in the the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), experts still recognize it and have a formal consensus definition for purposes of research, diagnosis, and treatment.

The symptoms of the disorder are likened to the fight-or-flight response to danger and can feel like someone stepping on your “emotional gas pedal.” (Ironically, my mom recalls watching Little House on the Prairie and screaming at her brother, whose crunch of the Doritos made it impossible to enjoy the series; these days, my dad says he sometimes feels pressured to eat his cereal in a different room.)

In more extreme cases, people may experience increased heart rate, blood pressure, and sweating, leading some to react vocally or avoid situations where the noises are present, for example. The root causes of misophonia are not well defined, but genetics and differences in the structure of the brain may all play a role.

Women are affected more than men, accounting for 55% to 83% of all cases, and while it can develop at any age, it’s most likely to develop in early teen years.

Gilbert was young—starring in the beloved TV series from the age of 10 to 19—and her family saw her as a kid who “would just glare at my parents and my grandmother and my siblings with eyes filled with hate,” Gilbert recalled. “I really just thought that I was rude. And I felt really bad. And guilty, which is an enormous component of misophonia, the guilt that you feel for these feelings of fight or flight. It’s a really isolating disorder.”

On set, while playing the earnest tomboy her dad called “Half Pint,” Gilbert felt incredibly frustrated and isolated by her own irritations. “If any of the kids chewed gum or ate or tapped their fingernails on the table, I would want to run away so badly,” Gilbert told People. “I would turn beet red and my eyes would fill up with tears and I’d just sit there feeling absolutely miserable and horribly guilty for feeling so hateful towards all these people—people I loved.”

Her misophonia persisted into her adult life, and as she raised her own two kids. “I had a hand signal that I would give, making my hand into a puppet and I’d make it look like it was chewing and then I’d snap it shut — like shut your mouth!” she says about her children. “My poor kids spent their whole childhoods growing up with me doing this. They weren’t allowed to have gum.”

Is there a treatment for misophonia?

After researching her symptoms and finding Duke Center for Misophonia in North Carolina, Gilbert realized there was a treatment for the disorder—cognitive behavioral therapy, or CBT, which is used to treat a variety of mental health conditions, including generalized anxiety, by helping people redirect their thinking patterns and manage their emotions.

Talk therapy as a way to identify and understand triggers can also be helpful.

“This is an emotional issue. It’s about self-regulation and self-control,” Gilbert told People. “I realized I could ride out these waves but that they’re not going to go away. They never go away. But now I have all these tools to enable me to be more comfortable and less triggered. It made me feel in control.”

More on mental health: