A millionaire levy in Massachusetts that New York City mayoral frontrunner Zohran Mamdani holds up as a model for taxing the rich has generated $3 billion more in revenue than expected without forcing significant high-profile departures from the state.

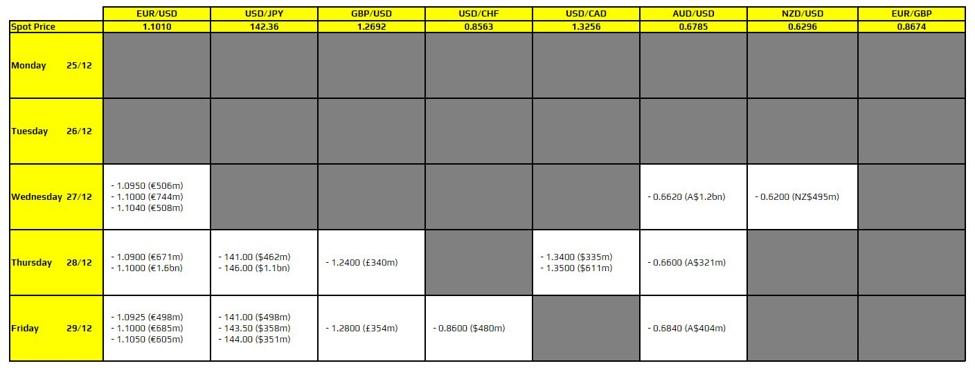

In the two years since the state started charging a 4% surtax on incomes over $1 million, the effort has created a $5.7 billion windfall, with the surplus being used to fund bridge repairs, bolster literacy programs and address the transportation system’s budget deficit.

While other states have progressive tax brackets, the Massachusetts law stands out structurally in its targeting of incomes that exceed seven figures. That has infuriated business leaders who complain it makes the state less competitive and drives away the wealthy. Several are even backing ballot proposals to lower the state income levy and limit how much tax revenue can be collected in any given year as a way to diffuse the millionaire’s fee.

Some high-profile names have moved away, including Robert Reynolds, the former chief executive officer of Putnam Investments. But other anecdotes of bold-faced names or companies ditching Massachusetts are harder to come by, in contrast to tales of departures from New York, Chicago and San Francisco. That may change as more Internal Revenue Service data is released in the coming months, potentially bolstering the case for the tax or providing evidence of how it can undermine a state’s appeal to the wealthy.

Boston Mayor Michelle Wu — whom Mamdani has called a role model — recently chastised executives for complaining about the tax. She contends that the region’s talent pool and livability are more important to its economic competitiveness.

Many high-income taxpayers are staying in the Boston area despite the tax hike.

“At the end of the day, I happen to believe it’s a phenomenal place to live,” said Sam Slater, a real estate developer who lives in the Boston suburb of Weston and pays the millionaire’s tax.

Slater, 41, could live anywhere: His real estate firm has holdings nationwide. He travels frequently for his side job producing films starring big names like Mark Wahlberg. His holdings including a piece of the National Hockey League’s Seattle Kraken. He even spent part of his childhood in West Palm Beach, Florida, a favorite refuge for wealthy executives looking to flee high taxes and winters.

But he’s staying put. His family has roots in the region, and they also like Boston’s culture, sports teams and seasons, Slater said.

Josh Isner, president of taser manufacturer Axon Enterprise Inc., said the millionaire’s tax makes it harder to recruit talent — particularly well-paid artificial intelligence specialists — to the Northeast hub the company opened in Boston last year. But the office is based in the city because “Boston breeds super-talented people,” he said earlier this year.

He lives in Massachusetts, rather than near the company’s headquarters in Scottsdale, Arizona, where income taxes are significantly lower. That’s largely because Massachusetts schools are so renowned, he said.

Massachusetts voters approved the surtax in 2022, with the levy applying to income that exceeds the $1 million threshold. Mamdani, who has maintained a large lead in polls ahead of New York’s Nov. 4 mayoral election, cited the Massachusetts policy as a success story when he floated his own millionaire’s tax proposal.

New York may prove different than Massachusetts. The Empire State already ranks dead last in the Tax Foundation’s competitiveness index with rates that are among the highest in the country. And while Mamdani has used billionaires as a foil in his campaign — he wants to raise levies on individuals and corporations to pay for his progressive agenda — Governor Kathy Hochul has ruled out approving increases.

In Massachusetts, with a buoyant stock market helping to swell wealthy residents’ taxable wealth, the millionaire’s tax generated an estimated $3 billion in the fiscal year that ended June 30, more than double what state lawmakers had budgeted, according to the Massachusetts Department of Revenue. Collections a year earlier similarly exceeded expectations. The surtax has generated $5.7 billion in total.

The extra cash has helped Governor Maura Healey ease the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority’s budget gap at a time when other states are slashing train and bus service. Healey’s now seeking to use $200 million of the money to address President Donald Trump’s cuts to research funding at Massachusetts institutions, one of the biggest threats to the state’s economy. The law that created the tax requires the funds to go toward education and transportation initiatives.

“People who thought this tax would backfire will have to concede now that it generates a substantial amount of additional revenue,” said Evan Horowitz, executive director of Tufts University’s Center for State Policy Analysis. Still, he estimates that for every dollar the millionaire’s tax brings in, the state is likely to lose 20 to 50 cents in income taxes from those who leave or adopt tax-avoidance strategies. Those indirect losses are hard to pinpoint, he said.

Individuals with incomes over $1 million were responsible for 35% of total payments in Massachusetts in 2022, the year before the millionaire’s tax took effect and the most recent period for which IRS data is available.

Some high-profile executives have indeed decamped for lower-tax states because of the surcharge. Reynolds, the former Putnam Investments CEO, cited the combination of the millionaire’s tax and the Massachusetts estate tax. He moved to Florida last year, shortly after Franklin Templeton acquired Boston-based Putnam.

The surtax “pushes you to make an earlier decision,” Reynolds said. The 73-year-old finance executive has been a fixture in Boston business circles for decades, having built Fidelity Investments’ 401(k) business before joining Putnam in 2008. He remains on the board of the Massachusetts Competitive Partnership, a collection of the state’s most powerful executives.

Business leaders continue to warn that even if wealthy residents didn’t abandon the state in droves in the tax’s first years, the departures will add up over time — and ultimately hurt Massachusetts more than it helps. They point out that $1 million incomes don’t go as far as they used to, particularly in a high-cost state like Massachusetts. The median home price in the greater Boston area surpassed $1 million in June before falling back under that threshold again.

“I haven’t been to one meeting in Boston since this passed where there haven’t been a number of people saying that they’re moving out of the state,” Reynolds said.

Other high-profile Massachusetts residents who have moved are reluctant to blame the tax. Steve Pagliuca, a longtime Bain Capital executive and Boston Celtics co-owner, has said his recent move to Florida was due to family reasons and his retirement from day-to-day work at Bain, not the tax. He recently offered to acquire the Connecticut Sun women’s professional basketball team and relocate it to Boston.

In the absence of clear data, supporters and critics of the millionaire’s tax alike have touted studies that support their arguments — even if they don’t tell the full story.

A study by a progressive research organization found that the number of millionaires in Massachusetts jumped by 39% from 2022 to 2024, with the authors concluding the surtax is an effective policy tool. The report’s data measured wealth, however, not the income figures that determine who is subject to the tax.

A separate survey conducted by a business advocacy group this year found that tax policy was the most-cited reason for residents’ moves elsewhere. Few of those surveyed are subject to the millionaire’s tax, though. The outflow of residents to other states also predates the surtax and reflects other factors such as high housing costs.

Slater, the real estate developer, has friends who left Massachusetts for places like Florida and Texas — both because of the millionaire’s tax and for other reasons. While he has no plans to follow them, he’s concerned Massachusetts could increase the surcharge or add other taxes in the future.

New increases have been on the table this year. Raise Up Massachusetts, the labor-backed group that proposed the millionaire’s tax, is now pushing to increase state duties on corporate foreign income. Healey also proposed new taxes on candy, prescription drugs and synthetic nicotine products — levies that the state legislature ultimately rejected.

Should Massachusetts tax wealthy individuals further, Slater said he can’t say with certainty he’d stick around.