In the race to make EVs cheaper and more profitable, companies are pulling just about every lever they can. But while improving battery technology often hogs the spotlight, automakers are investing heavily into changing how the rest of the car is made.

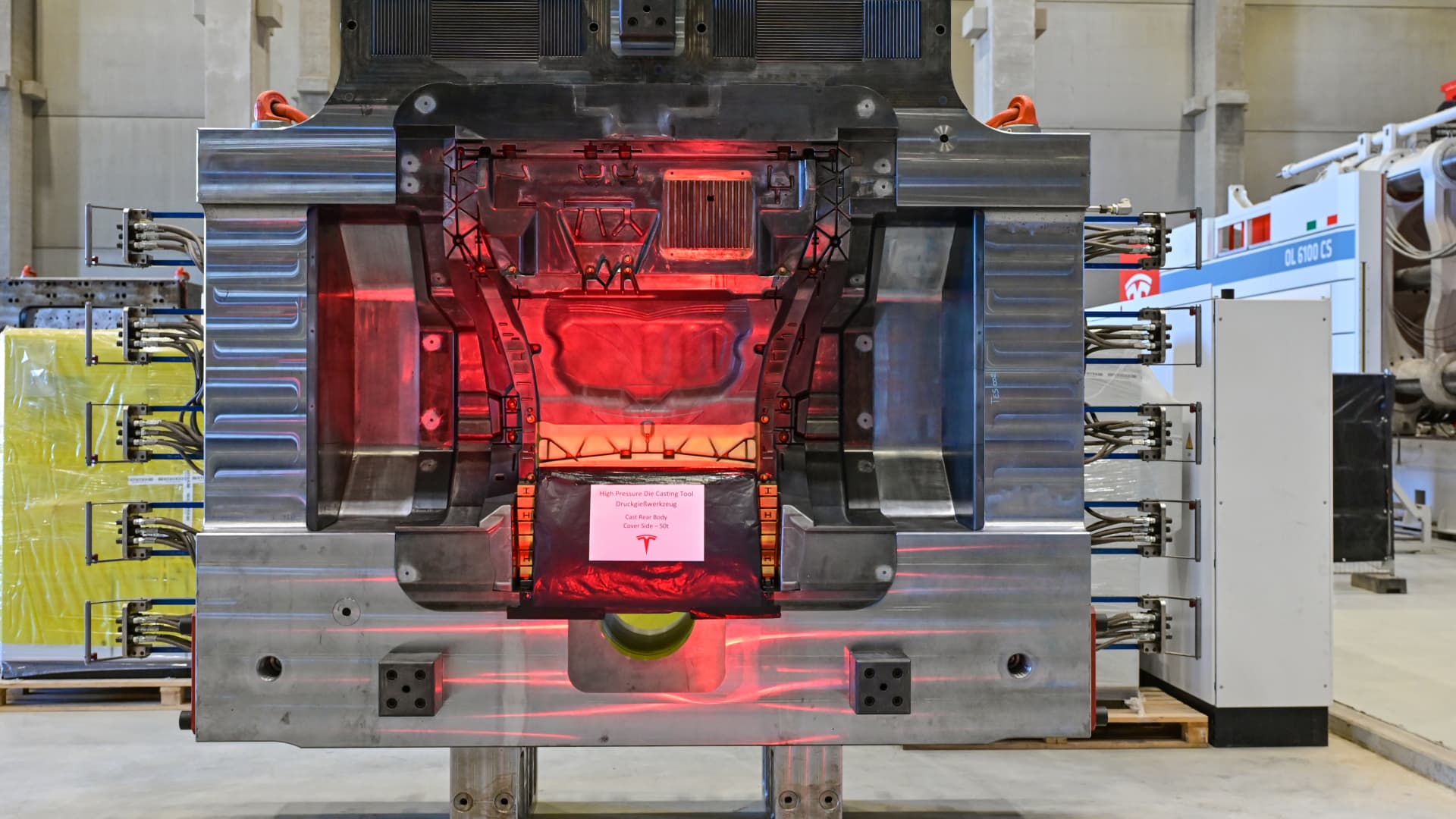

One such method is megacasting, or gigacasting, as Tesla calls it.

Gigacasting is a form of die-casting — pouring materials like molten aluminum into large molds to form parts. Die-casting has been around for awhile, but the American automaker headed by Elon Musk has been credited with pushing the envelope, said Shea Burns, a partner at research firm AlixPartners who studies auto manufacturing.

Tesla said the process works to reduce weight and dramatically improve manufacturing efficiency.

For example, the front and rear portions of the early Model 3 chassis each contained more than 70 parts, according to Tesla. The same two portions on the very similar Model Y are now just one part each.

“A cast rear body or front body is lighter, cheaper, better noise vibration or harshness, much easier to manufacture,” Musk told analysts after Tesla released its second-quarter earnings of 2023. “I think it’s basically going to be how all cars are made in the future.”

Other automakers have announced their own investments: Toyota, Ford Motor, General Motors, Hyundai, Nissan, and Volvo.

“I see tons of opportunities going forward,” said Erik Severinson, chief product and strategy officer for Volvo. Reducing weight ultimately means more range for the customer, and substituting one large megacast for dozens of stamped parts reduces labor and boosts production, he said.

“If you want to make an efficient electrified car, you need to have more aluminum, you need to have less parts, you need to have less complexity,” he said.

But those who study the field say that while megacasting is exciting, it faces technical challenges. Die-casting always bears the risk that the material won’t fully or properly fill the mold, allowing “voids” or air bubbles to occur, critics say. Those voids could pose structural risks.

There is also a higher scrap rate. About 15 pieces out of every 1,000 have to be thrown out, Burns said. For stamped steel, the rate is 10 of a 1,000.

There are also concerns that any damage to large megacasts will be tougher or more expensive to repair or replace, simply because of their sheer size.

Even in low-speed crashes that occur at about 10 miles per hour, “you have a deformation of these big parts,” said Wolfram Volk, a professor of metal forming and casting at the Technical University of Munich in Germany. “And currently the car is impossible to repair.”

Volk added he has spoken with German premium carmakers such as BMW and Volkswagen, who so far have steered away from the technique.

For its part, Tesla has disputed that castings are tougher to repair. The company’s vice president of engineering, Lars Moravy, said on that second-quarter 2023 earnings call that replacing a specific cast part on a Tesla car, a rear rail, was 10 times cheaper and three times faster than a comparable stamped part.

Severinson views repair as a solvable challenge: “There is a solution to repairing also a casted rear floor,” he said. “It’s not an easy operation, but it’s definitely doable.”

Tesla, meanwhile, has reportedly backed away from an ambitious plan to create the entire underbody of its vehicles in one single piece. Burns and Volk say that might be a sign that the company is hitting some technical limits. Currently, the underbodies of the Model 3 and Model Y are cast in three pieces.

“You should have a balanced view on this technology,” Volk said. “It’s really a big step forward in casting.” But, he added, no one knows if the promises will be fulfilled or if obstacles will stymie development. “It’s a open game.”