But new research finds that these changes to retirement savings programs aren’t having the hoped for effects when they are implemented in the workplace.

James Choi, a professor at the Yale School of Management, is behind much of the research over the past few decades on automatic enrollment and other savings nudges that has led to widespread adoption of these measures by the public and private sectors alike. Auto-enrollment occurs when an employee must opt out of contributing to their 401(k) or 403(b) retirement plan, rather than opting in; workers must actively choose not to contribute. Once auto-enrolled, contributions are then auto-escalated (another of the popular “nudges”), meaning they are increased by a pre-determined percentage (typically 1%) each year, unless the employee opts out.

Previous research has indicated that removing the effort to sign up or increase their contributions leads workers to save more. But now, Choi and a team of researchers are back with a look at how workers are actually responding to the nudges put into place by their companies.

In a new paper entitled “Smaller than We Thought? The Effect of Automatic Savings Policies,” Choi and his colleagues write that auto-enrollment and default auto-escalation are less effective at increasing employees’ retirement savings than they previously found. Studying nine workplace 401(k) plans, the researchers find auto enrollment increases net contributions by 0.6% of income per year, and auto-escalation by only 0.3% of income per year. Just 40% of workers with an auto-escalation default actually increase their savings rate on their first escalation date, and increasingly more opt out over time.

The smaller effect isn’t necessarily due to auto-enrollment itself being a bad tool. But in the U.S., employees change jobs so often that the nudges simply don’t get the time they need to actually make a difference. Cash leakage—employees cashing out their accounts when they leave one job instead of rolling over the money into a new plan—and vesting requirements also diminish the effects, they find. Employees who stay at one firm for a longer period of time, however, do see the benefits of these nudges payoff.

“The exact magnitude will of course differ when we move across populations,” Choi tells Fortune. “But what is quite general is we know that a lot of this money gets withdrawn when people leave their jobs.”

As for auto-escalation, many more employees who stay at the same firm opt out of the policy than the researchers previously thought would do so. And when others leave one job, they either don’t increase their contribution rate at the next, or start anew at a lower baseline, negating the benefits.

Choi says this all makes some sense. When workers are struggling to pay bills—as many are now due to a higher cost of living—one of the first things they tend to cut back on is their savings rate.

“I don’t think that auto-policies and savings plans are bad. I think they still pass the cost-benefit analysis, they have a significant effect,” Choi says. “But they aren’t as huge of an effect as we initially thought because they are being undone on some of these margins.”

A step back for savings progress

It’s an unexpected development for policies that have been embraced by financial experts and politicians as easy ways to aid in fixing America’s retirement savings crisis.

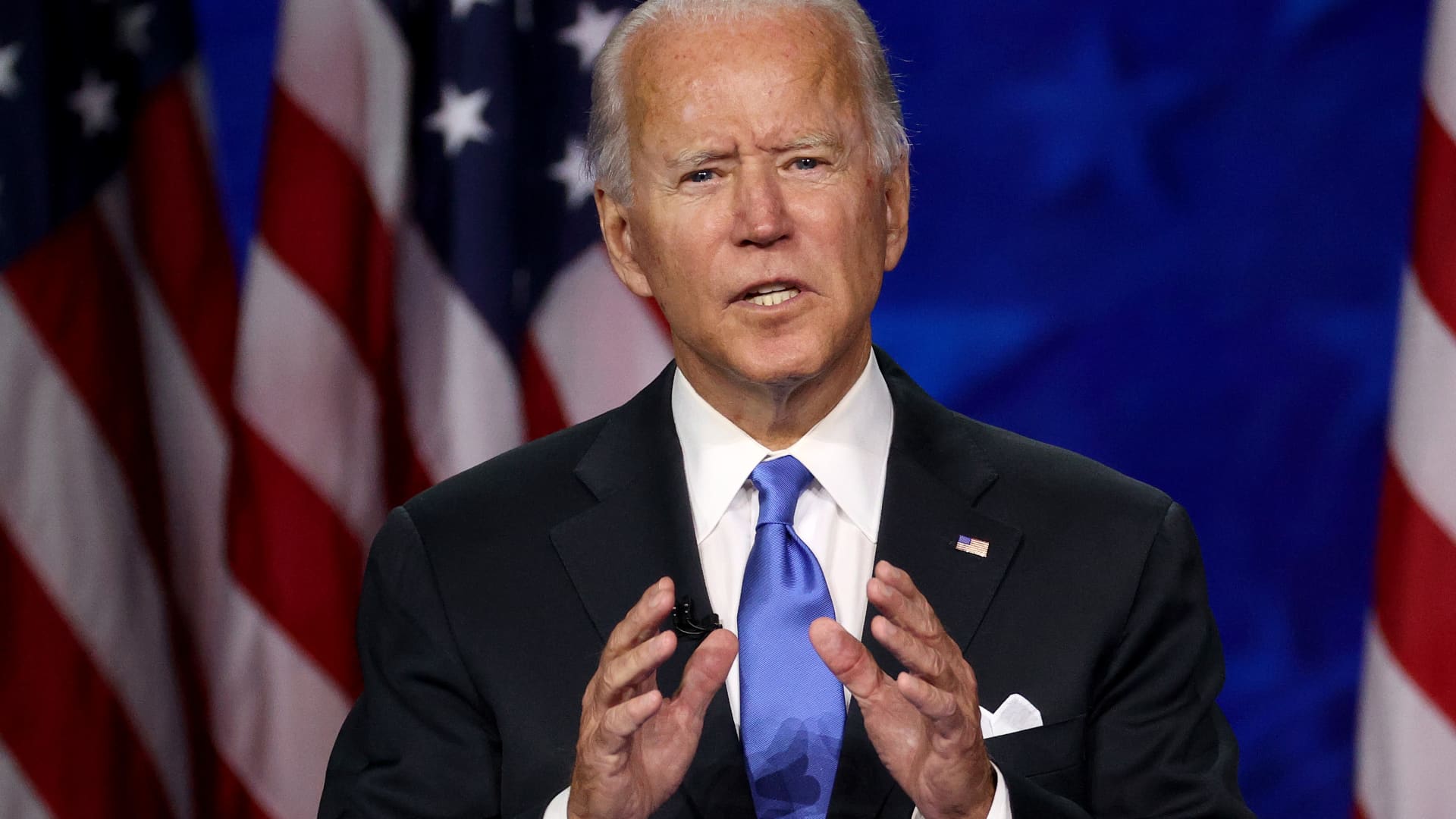

In fact, 10 states require employers that do not offer a 401(k) plan to automatically enroll employees in an Individual Retirement Account, or IRA, according to the report. More recently, President Joe Biden signed the SECURE Act 2.0 into law, which requires most newly established 401(k) retirement savings plans to automatically enroll new employees and auto-escalate their contribution rate by default, among other provisions.

None of this is to say that auto-enrollment and escalation policies don’t have a place in the retirement savers toolkit. Choi says more research is needed given that this new research just looks at nine different workplaces when there are hundreds of thousands of others. And other research has indicated that these same policies have broadly helped younger generations save more than older ones at an earlier age.

But other changes might be more meaningful, says Choi. For example, instead of increasing the percentage of income contributed each year someone works at a specific firm, Choi suggests the employer should base the default contribution rate on the age or salary of each employee.

A more dramatic change, he says, would be compulsory savings, or mandated contributions to a 401(k) or IRA-type account that cannot be touched before retirement. Of course, that would be an uphill battle to establish in the U.S., where individual choice reigns supreme (that said, the current Social Security system is a form of compulsory savings).

“Are we going to nudge ourselves to savings nirvana? It looks like no. We’ll get a modest increase in savings rate,” Choi says. “They are still great, just not as great as we thought.”