More than 6 million Americans receive paper tax refund checks annually. Often, those refunds go to purchase groceries or pay the bills. But this year, those taxpayers may be surprised to learn that the paper check they’re waiting for no longer exists.

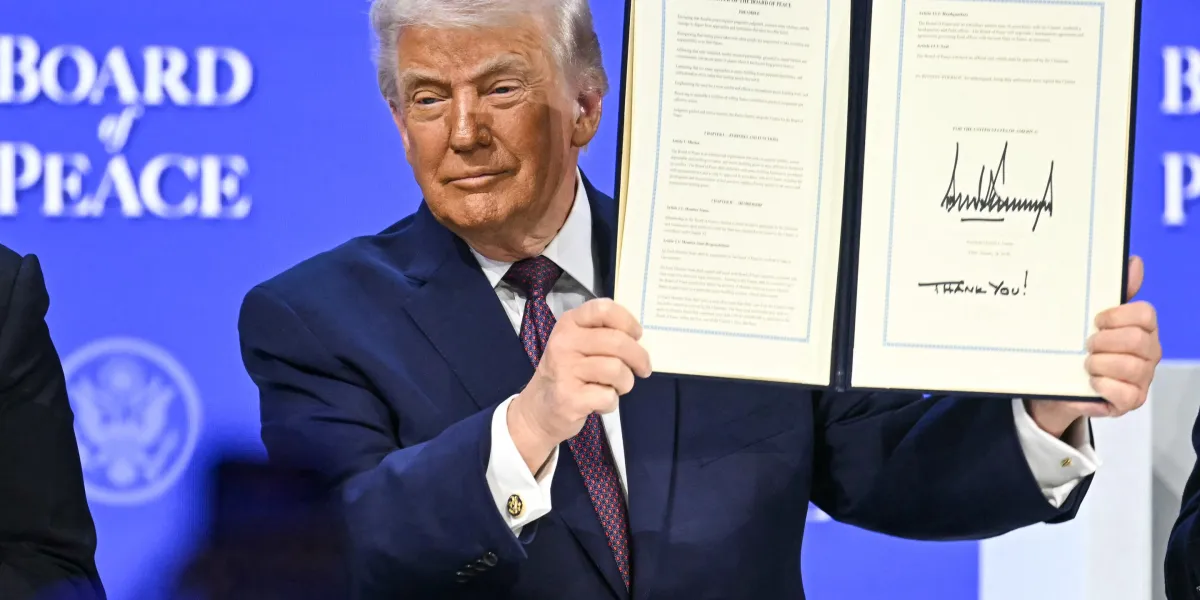

That’s because of executive order 14247, which President Donald Trump signed in 2025. It directed the Treasury Department to stop issuing paper checks for tax refunds.

The executive order has its fans. Nacha, the organization that runs the network that electronically moves money between financial institutions, says the new rules could save the government US$68 million each year. The American Bankers Association is also excited, predicting the move will help people save on check-cashing fees. Other supporters argue the change will prevent mail theft and check fraud.

But what about the 6 million Americans without bank accounts – the so-called “unbanked”? Watchdogs warn that they will suffer if exceptions and outreach fall short.

As a professor who specializes in tax law, I think those concerns are valid.

Reform could leave the unbanked behind

Shifting to electronic payments is a classic modernization effort. So how could that be bad?

The problem is that a sizable number of Americans have no bank account. Twenty-three percent of people who earn under $25,000 were unbanked in 2023. Only 1% of people earning over $100,000 in 2023 lacked a bank account.

Black and Hispanic Americans, young adults, and people with disabilities are more likely to be unbanked than other people, and 1 in 5 unbanked households include someone with a disability.

Low-income families often use their refunds to pay for basics such as food and rent. And under the status quo, unbanked people already lose a large slice of those refunds to fees. Check cashers, for example, can charge up to 1.5% for government checks in New York, up to 3% in California, and even more in other states.

But the unbanked might find that they’re paying even higher fees in a post-check world. They might, for example, use paid tax preparation services to access refund loans. The federal courts and investigative journalists have discussed ways that prepaid tax preparers engage in false advertising and overpriced services.

Or they might forgo their tax refunds entirely.

Geography, race and the digital-banking divide

Where people live affects their access to banking.

Gaps in broadband coverage and lack of public transportation to reach libraries make computer access a problem for poor and rural people.

In so-called “banking deserts” – communities with few or no bank branches – people are more likely to use costly alternatives such as payday lenders and check-cashing services. Black-majority communities face distinct banking desert challenges, for both poor and middle class Black families. That’s because a middle-income Black family is more likely to live in a low-income neighborhood than a low-income white family.

Taken together, these barriers mean that many Americans who are legally entitled to tax refunds could soon struggle to receive them.

What should government do now?

The government is aware of the problem. The IRS promises that “limited exceptions” will be available to people who don’t have bank accounts, and that more guidance is on the way.

In the meantime, the agency stepped up on the day after Thanksgiving to urge people without bank accounts to open them, or to check whether their digital wallets can accept direct deposits, while the Bureau of the Fiscal Service has provided a website with all sorts of information for people who need to get up to speed on electronic payments.

For the moment, it’s unclear just how effective these efforts will be. Perhaps this is why the American Bar Association is urging Treasury to keep issuing paper refund checks unless Congress passes a law rather than relying on an executive order.

Consumer groups have urged the Treasury Department to fund robust exceptions, plain-language help lines and no-fee default payment options while also banning junk fees on refund- related cards and mandating easy access to cash-out at banks or retailers.

The problem is that the Treasury Department has lost over 30,000 employees and $20.2 billion in funding since January 2025. Add in the lingering effects of the last government shutdown, adopting a new system for tax filing and refunds might be too much to expect for the 2026 tax season.

Beverly Moran, Professor Emerita of Law, Vanderbilt University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()