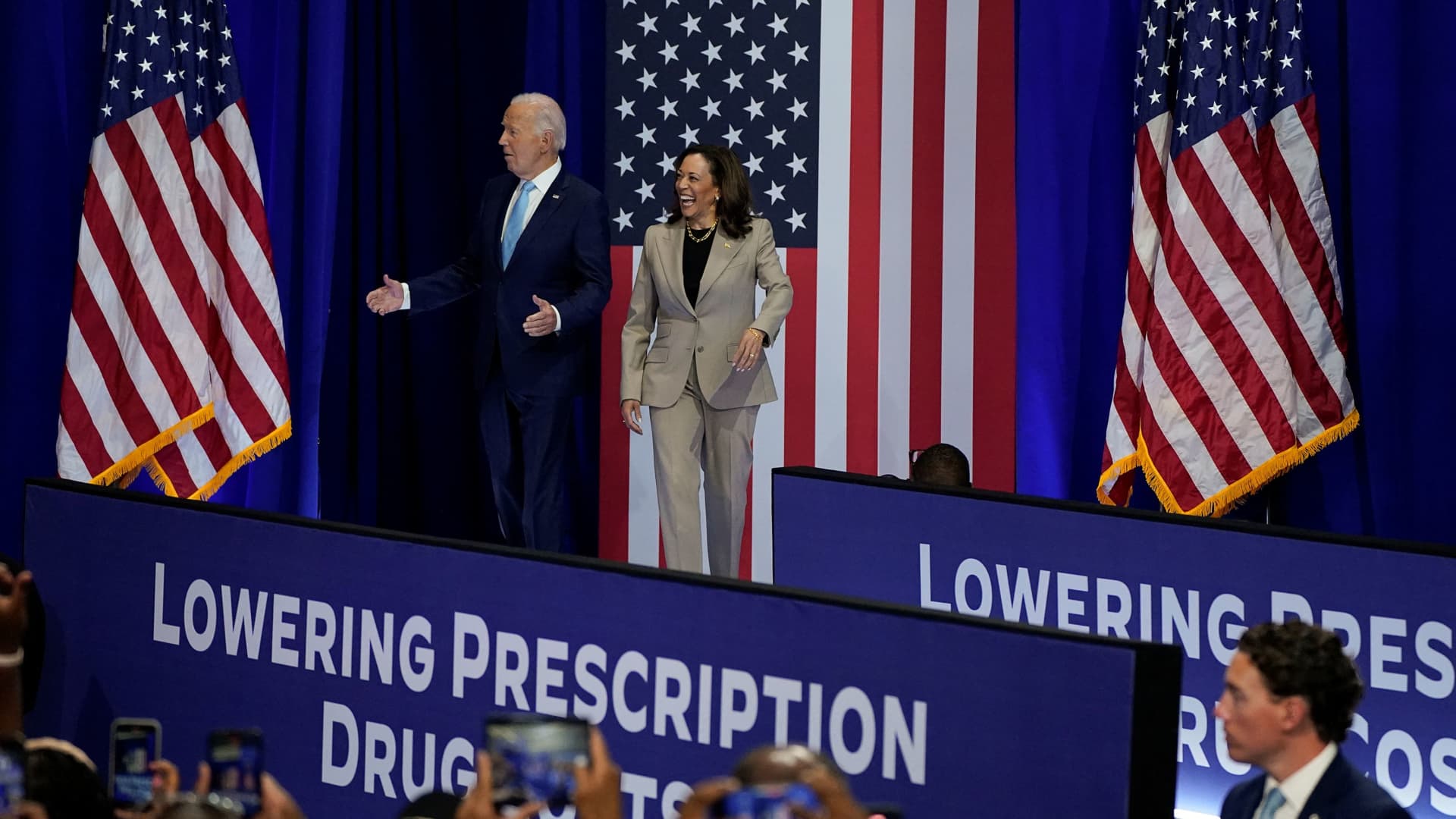

U.S. President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris walk out together, at an event on Medicare drug price negotiations, in Prince George’s County, Maryland, U.S., August 15, 2024.

Ken Cedeno | Reuters

The Biden administration on Thursday reached a milestone in Democrats’ decades-long quest to use Medicare to drive down prescription drug costs, releasing new prices for the first 10 medications subject to negotiations between the federal program and drugmakers.

But the announcement is just the beginning of a controversial, multi-round process that could save more money for taxpayers and older Americans and put more pressure on pharmaceutical companies over time. It’s a key provision of President Joe Biden’s signature Inflation Reduction Act, which was signed into law almost exactly two years ago.

The agreed-upon prices, which go into effect in 2026, set the precedent for the future rounds of negotiations that will kick off next year. Those talks will likely affect prices in the coming years for dozens more widely used drugs made by the largest pharmaceutical companies in the world.

“I think the expectation that people should have is that this is just the start. These are just the first ten drugs,” said Leigh Purvis, a prescription drug policy principal with AARP Public Policy Institute, an arm of the influential lobbying group that represents people older than 50, which has advocated for Medicare’s negotiation powers.

“Sometimes people get caught up in the fact that their drug isn’t on the list, but it will be on the list at some point in the future if they’re taking a drug that’s resulting in high costs,” Purvis added.

It’s unclear how much lower the negotiated prices are than the current net prices of the first 10 drugs, which are heavily rebated by Medicare Part D plans. Those net prices aren’t publicly available, making it difficult to know how much a Medicare plan and a patient would actually save on a given drug when the negotiated prices start in 2026. Copays could also differ depending on the Part D plan a patient has.

“It’s hard to know the starting point, because … those numbers are not publicly available,” said Tricia Neuman, executive director for the Program on Medicare Policy at health policy research organization KFF, referring to net prices after rebates.

Still, the Biden administration estimates that the new negotiated prices for the medications will lead to around $6 billion in net savings for the Medicare program and $1.5 billion in out-of-pocket savings for beneficiaries in 2026 alone.

The negotiations “seemed to go relatively smoothly – the aggregate savings are fairly impressive,” Neuman said. She added as prices of more drugs are hashed out during future rounds, it will “increase the level of savings over time.”

The price talks could also put more pressure on drugmakers in the coming years. Many of the medications in the first round of negotiations are already nearing patent expirations that will open the market to competition from cheaper generics, which will take a bite out of revenue.

For example, Bristol Myers Squibb‘s blood thinner Eliquis is slated to lose patent exclusivity in the U.S. starting on April 1, 2028. The blockbuster drug also faces patent expirations in certain EU markets in 2026.

But over time, drugs much further from losing market exclusivity could be selected for future rounds of negotiations, Leerink Partners analyst David Risinger said in a research note Thursday.

By February 2025, the Biden administration will select up to 15 more drugs that will be subject to the next round of price talks, with new prices going into effect in 2027. Manufacturers will have until the end of February to decide whether to participate in the program — a no-brainer for companies as they face steep excise taxes or the loss of access to the federal Medicare and Medicaid programs if they do not.

“It will start to get more painful over time,” Jeff Jonas, a portfolio manager at Gabelli Funds, said in a statement Thursday. He noted, for instance, that the next round of price talks will likely include Novo Nordisk‘s top-selling diabetes drug Ozempic.

Jonas added that there was “some speculation that the government went easy on the pharma companies this year given that it is both an election year and the first time they’re doing this.”

After the second round, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services can negotiate prices for another 15 drugs that will go into effect in 2028. The number rises to 20 a year starting in 2029.

CMS will only select Medicare Part D drugs for the medicines covered by the first two years of negotiations. It will add more specialized drugs covered by Medicare Part B, which are typically administered by doctors, for the round that takes effect in 2028.

That could be a bigger threat to the pharmaceutical industry, as Medicare Part B drugs aren’t discounted as steeply as medicine covered by Part D.

“My assumption, since rebates are limited, is they have farther to fall versus Part D drugs that are heavily rebated,” Risinger told CNBC in an interview, referring to medications covered by Part B.

Jonas noted that negotiations for 2028 price changes could include some big cancer drugs, such as Merck’s blockbuster chemotherapy Keytruda.

Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic presidential nominee, would likely try to expand the scope of negotiations if elected and “likely be more aggressive on the discounts,” Jonas said.

But Neuman said that whether she can pass a law to bolster the policy will depend on which party controls the House and Senate. Harris herself had to cast a tiebreaking vote in the Democratic-held Senate to pass the original law.

“There’s some interest among Democrats in Congress in doing that, but obviously the law will depend on which party is in control,” Neuman said.

The pharmaceutical industry has argued that the negotiations could cut into their revenue, profits and innovation in the long term.

For example, Steve Ubl, the CEO of the pharmaceutical industry’s biggest lobbying group, PhRMA, said in a statement Thursday that the price talks could result in fewer treatments for cancer, mental health, rare diseases and other conditions because it “fundamentally alters” the incentives for drug development.

Medicare can start negotiating prices on small-molecule drugs as early as nine years after they receive U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval, compared with 13 years for biologics. Small molecule drugs are made of chemicals that have low molecular weight, while biologic medicines are derived from living sources such as animals or humans.

The industry has argued that the distinction is going to deter companies from investing in small-molecule drugs.

— CNBC’s Angelica Peebles contributed to this report