Hot, humid days are already uncomfortable—now imagine that discomfort multiplied as you go all-out during an evening pickleball game or lunchtime run. For some, that heat can be enough to make you not want to exercise outside at all.

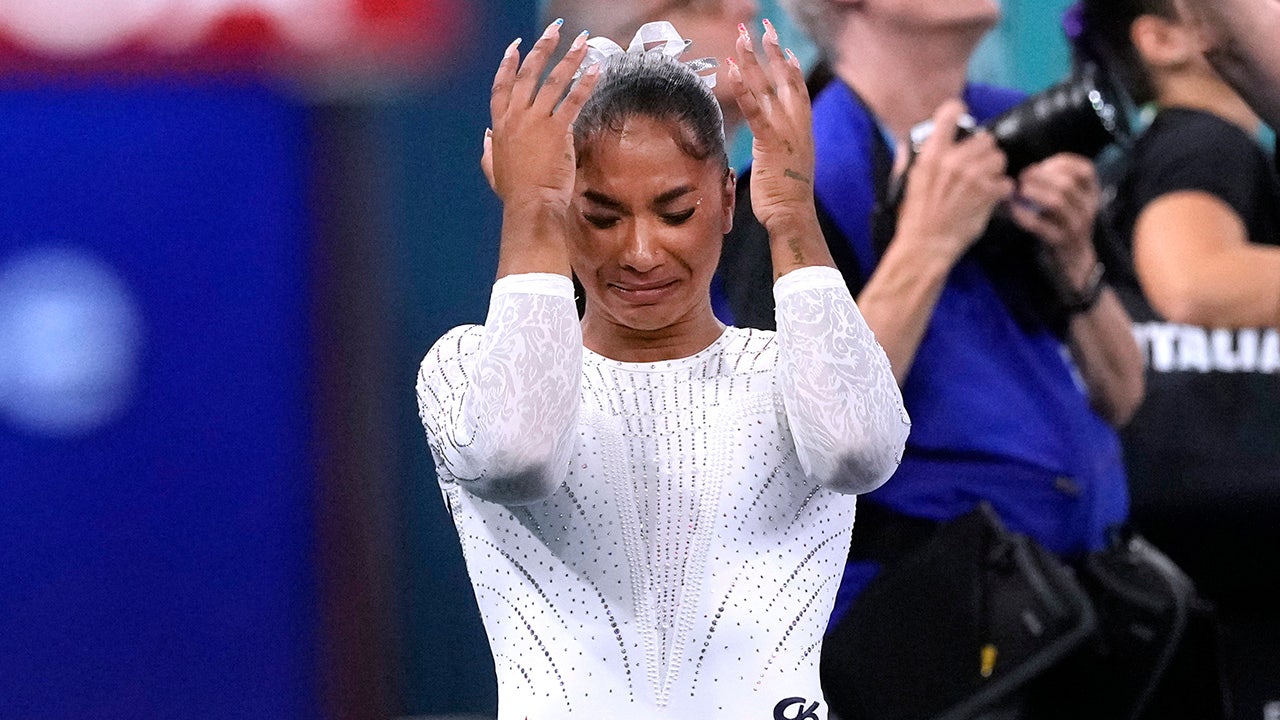

But, now is the time to use that workout inspiration we’re all getting from the summer Olympics—because, according to experts, working out in the heat can help us get fitter, if we do it correctly.

Why is exercising in the heat so hard?

Higher temperatures and stifling humidity make the body work harder.

“I always think that exercise and heat is a big cardiovascular challenge,” says Chris Byrne, registered physiotherapist and senior lecturer at the University of Exeter.

That’s because our cardiovascular system has to juggle two substantial jobs: circulating blood, oxygen, and metabolic fuel to our muscles, and cooling our bodies down.

“There’s competing demands. Some of…the cardiac output from the heart needs to be channeled into losing heat,” Byrne says. “That can start causing problems.”

That’s when what Byrne calls “heart rate drift” can happen. In cooler conditions, your heart rate will remain steady while maintaining the same effort during exercise. In the heat, despite running at the same speed, for example, heart rate starts to drift up. “And that is a sign of the cardiovascular system putting more focus on heat loss,” Byrne says.

What is heat adaptation?

“Our physical fitness in the hot environment can certainly be improved through things like heat training,” says Chris J. Tyler, who researches the impact of environmental extremes on the human body at the University of Roehampton in Britain.

With properly paced and progressive training, our bodies can not only adjust to heat, but we’ll also be able to work out harder at hotter temperatures, Tyler says.

That’s where three vital physical adaptations come in:

- lower core body temperature

- higher blood volume, which leads to higher stroke volume—the amount of blood ejected by heart beats

- lower resting heart rate.

Those adaptations interact to make your cardiovascular system function more efficiently, with a higher volume of blood leaving the heart per minute, Byrne explains.

Heat adaptation leads to a lower resting core body temperature in order to improve our ability to lose heat, Byrne says. Our body temperature can lower from the standard 98.6 F to as low as 97.7 F—giving us a lower starting temperature as we begin exercising, meaning we’ll start sweating earlier, cooling down earlier, and we won’t get as hot as quickly.

Byrne says we also start to sweat earlier at our newly lowered body temperature. That means our bodies have adapted to trigger heat loss mechanisms more quickly, which helps us cool down.

With these adaptations, you can reach much higher cardiac outputs—or much harder efforts—during exercise, Byrne says.

“These adaptations allow the heart to function more efficiently to meet those dual tasks of supplying fuel to working muscles and losing heat from working muscles,” Byrne says.

Here’s how safely heat train

Heat adaptations can occur quite quickly, says Tyler, if you do it right.

“The adaptation isn’t getting hot—it’s getting hot and staying hot,” Tyler says. “It’s not how long you exercise for, it’s how long you’re hot.”

Byrne advises to work out for at least 30 minutes every day, or 60 minutes every other day, if you’re running or cycling—at whatexperts would call “submaximal effort.”

Even if your heart is pounding in the heat, your core temperature may not be high enough to reap heat adaptation benefits. It’s most ideal to get that core temperature high and keep it high for at least 30 minutes, Byrne says, since it takes a longer time for body temperature to rise and fall than it does heart rate.

You can start to see those benefits as soon as five to seven days into daily training, Tyler says. If you’re exercising more like every other day, then he says you can expect to see those adaptations in about two weeks, maybe sooner.

When it comes to other types of exercise—like pickleball, tennis, or football—which include high intensity intervals, Byrne says heat adaptation is possible, even with brief rest periods between sets or games, since body temperature takes a while to fall.

“With something like tennis, you’ll probably see a rise in body temp, and if there’s a break in between sets you’ll probably see a subtle fall, but quickly it’ll be back up again,” Byrne says.

Even with adaptations, training in hot conditions is hard, especially when you first start out. Tyler says the key is to start slow, gradually increasing the difficulty.

“Just like you wouldn’t go to the gym and instantly try and lift 400 pounds, you might start light and get heavier as you progress,” Tyler says. If you go too quickly, he warns, you could get injured or suffer from heat-related illnesses. On the other hand, if you don’t increase the difficulty at all, you likely won’t see your fitness progress much.

Starting slowly can look like going for a 30-minute jog with walk breaks, Byrne says, and then building up gradually from there.

The average athlete should pay attention to heart rate and rate of perceived effort, or RPE, Tyler says. Once you see your heart rate lower during the same workouts and feel that they become easier than when you first started heat training, that’s when you feel those adaptations happening in real time.

How to stay safe in the heat

Safety should be your number one priority. Heat illnesses are real—and can be deadly in the most extreme cases.

Byrne advises to only exercise in what you can handle—if you feel you’re overheating, slow down or stop immediately and cool down. Humidity can be a dangerous factor as well, he says, as the moisture in the air prevents you from sweating—one of the most vital things our body does to cool down.

Here’s advice from experts and the CDC on how to stay safe while going after summer goals:

- Stay hydrated. Byrne advises to keep fluids and electrolytes on hand, especially for if you’re working out longer than 60 minutes.

- Don’t over hydrate: drinking too much plain water can be dangerous.

- Take it slow. Byrne advises beginners to start with something like a 30-minute jog with one-minute walking intervals dispersed throughout.

- Take some time off if you’re sick or have been sick recently.

- Slow down or stop if you feel overheated.

- Drink more water than usual, and don’t wait until you’re thirsty to drink more.

- Wear loose, lightweight, light-colored clothing.

- Look for signs of heat illnesses. Seek shade and hydrate immediately if you feel symptoms like dizziness, delirium, nauseousness, headaches, or muscle cramps.

- People over 65—who aren’t marathon runners or highly trained—and children should avoid strenuous outdoor activity in the summer heat.

More on working out: