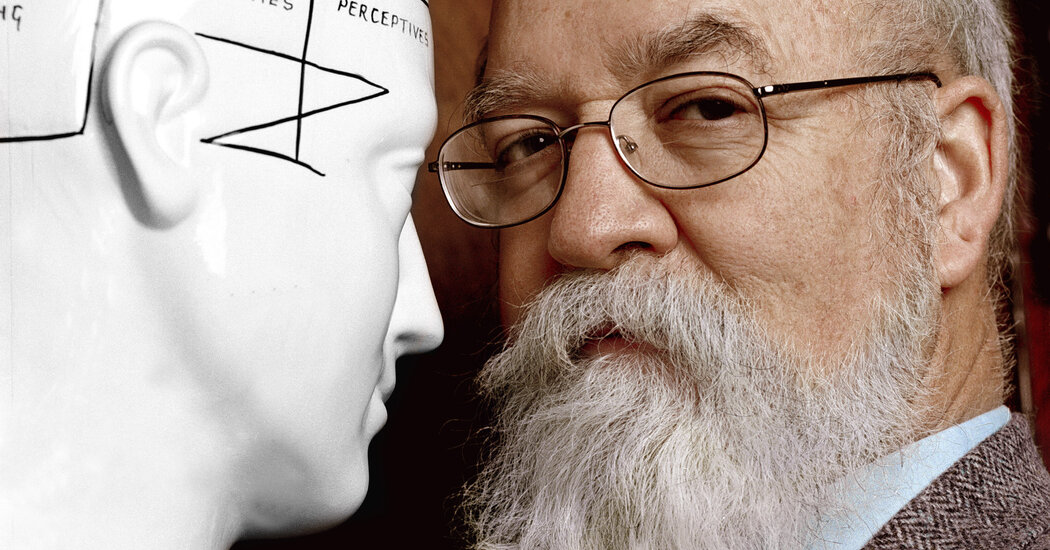

Daniel C. Dennett, some of the broadly learn and debated American philosophers, whose prolific works explored consciousness, free will, faith and evolutionary biology, died on Friday in Portland, Maine. He was 82.

His dying, at Maine Medical Heart, was brought on by issues of interstitial lung illness, his spouse, Susan Bell Dennett, mentioned. He lived in Cape Elizabeth, Maine.

Mr. Dennett mixed a variety of information with a simple, usually playful writing type to succeed in a lay public, avoiding the impenetrable ideas and turgid prose of many different modern philosophers. Past his greater than 20 books and scores of essays, his writings even made their manner into the theater and onto the live performance stage.

However Mr. Dennett, who by no means shirked controversy, usually crossed swords with different famed students and thinkers.

An outspoken atheist, he at occasions appeared to denigrate faith. “There’s simply no polite way to tell people they’ve dedicated their lives to an illusion,” he mentioned in a 2013 interview with The New York Times.

In response to Mr. Dennett, the human thoughts is not more than a mind working as a collection of algorithmic capabilities, akin to a pc. To imagine in any other case is “profoundly naïve and anti-scientific,” he advised The Occasions.

For Mr. Dennett, random likelihood performed a higher function in decision-making than did motives, passions, reasoning, character or values. Free will is a fantasy, however a needed one to realize individuals’s acceptance of guidelines that govern society, he mentioned.

Mr. Dennett irked some scientists by asserting that pure choice alone decided evolution. He was particularly disdainful of the eminent paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, whose concepts on different elements of evolution had been summarily dismissed by Mr. Dennett as “goulding.”

Not surprisingly, Mr. Dennett’s writings might elicit strong criticism as effectively — to which he typically reacted with fury.

Daniel Clement Dennett III was born on March 28, 1942, in Boston, the son of Daniel Clement Dennett Jr. and Ruth Marjorie (Leck) Dennett. His sister, Charlotte Dennett, was a lawyer and journalist.

Mr. Dennett spent a part of his childhood in Beirut, Lebanon, the place his father was a covert intelligence agent posing as a cultural attaché in america Embassy, whereas his mom taught English on the American Neighborhood Faculty.

He graduated from Harvard College in 1963 and two years later earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from Oxford College. His dissertation started a lifelong quest to make use of empirical analysis as the idea of a philosophy of the thoughts.

Mr. Dennett taught philosophy on the College of California, Irvine, from 1965 to 1971. He then spent virtually his complete profession on the college of Tufts University, the place he was director of its Heart for Cognitive Research and most not too long ago an emeritus professor.

His first guide to draw widespread scholarly discover was “Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology,” revealed in 1978.

In it, Mr. Dennett asserted that a number of choices resulted in an ethical selection and that these prior, random deliberations contributed extra to the way in which a person acted than did the last word ethical resolution itself. Or, as he defined:

“I am faced with an important decision to make, and after a certain amount of deliberation, I say to myself: ‘That’s enough. I’ve considered this matter enough and now I’m going to act,’ in the full knowledge that I could have considered further, in the full knowledge that the eventualities may prove that I decided in error, but with the acceptance of responsibility in any case.”

Some main libertarians criticized Mr. Dennett’s mannequin as undermining the idea of free will: If random choices decide final selection, they argued, then people aren’t liable for his or her actions.

Mr. Dennett responded that free will — like consciousness — was primarily based on the outdated notion that the thoughts ought to be thought-about separate from the bodily mind. Nonetheless, he asserted, free will was a needed phantasm to keep up a steady, functioning society.

“We couldn’t live the way we do without it,” he wrote in his 2017 guide, “From Bacteria to Bach and Back: The Evolution of Minds.” “If — because free will is an illusion — no one is ever responsible for what they do, should we abolish yellow and red cards in soccer, the penalty box in ice hockey and all the other penalty systems in sports?”

Already with the 1991 publication of his guide, “Consciousness Explained,” Mr. Dennett had expounded his perception that consciousness could possibly be defined solely by an understanding of the physiology of the mind, which he considered as a type of supercomputer.

“All varieties of perception — indeed all varieties of thought or mental activity — are accomplished in the brain by parallel, multitrack processes of interpretation and elaboration of sensory inputs,” he wrote. “Information entering the nervous system is under continuous ‘editorial revision.’”

By the Nineties, Mr. Dennett had more and more sought to clarify the event of the mind — and illusions of a separate consciousness and free will — when it comes to the evolution of human beings from different animal life.

He believed that pure choice was the overwhelming issue on this evolution. And he insisted that bodily and behavioral traits of organisms developed primarily by their helpful results on survival or copy, thus enhancing an organism’s health in its surroundings.

Critics, like Mr. Gould, cautioned that whereas pure choice was essential, evolution would additionally should be defined by random genetic mutations that had been impartial and even considerably damaging to organisms, however that had change into mounted in a inhabitants. In Mr. Gould’s view, evolution is marked by lengthy durations of little or no change punctuated by brief, speedy bursts of serious change, whereas Mr. Dennett defended a extra gradualist view.

Underlying the more and more acrimonious debate between the students was a pure friction within the scientific and philosophical communities over which facet merited extra credibility with reference to evolution.

Mr. Dennett additionally plunged into controversy along with his strident views on atheism. He and a colleague, Linda LaScola, researched and revealed a guide in 2013, “Caught in the Pulpit: Leaving Belief Behind,” primarily based on interviews with clerics of assorted denominations who had been secret atheists. They defended their resolution to proceed preaching as a result of it supplied consolation and wanted ritual to their congregations.

Interviews with clergy from the guide turned the idea of a play by Marin Gazzaniga, “The Unbelieving,” which was staged Off Broadway in 2022.

Eight years earlier, Mr. Dennett’s views on evolutionary biology and faith had been the topic of “Mind Out of Matter,” a 75-minute-long musical composition by Scott Johnson carried out in a seven-part live performance at a theater in Montclair, N.J. The composer used recordings from Mr. Dennett’s lectures and interviews.

Mr. Dennett’s fame and following prolonged to each side of the Atlantic. As he grew older, he was accompanied by his spouse on his lecture excursions overseas. Along with his spouse, his survivors embrace a daughter, Andrea Dennett Wardwell; a son, Peter; two sisters, Cynthia Yee and Charlotte Dennett; and 6 grandchildren.

Whereas Mr. Dennett by no means held again in contradicting the views of different students, he bristled at harsh feedback about his personal work. This was particularly the case when Leon Wieseltier, a widely known author on politics, faith and tradition, strongly criticized Mr. Dennett’s 2006 greatest vendor, “Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon,” in The New York Times Book Review.

Contending that Mr. Dennett was illiberal of people that didn’t share his fundamental perception that science might clarify all human circumstances, Mr. Wieseltier concluded: “Dennett is the sort of rationalist who gives reason a bad name.”

In a prolonged, angry rebuttal, Mr. Dennett denounced Mr. Wieseltier for “flagrant falsehoods” that demonstrated a “visceral repugnance that fairly haunts Wieseltier’s railing (without arguments) against my arguments.”

An earlier, extra optimistic appraisal of one other of his greatest sellers, “Kinds of Minds: Toward an Understanding of Consciousness” (1996), that ran in New Scientist journal may need come closest to explaining Mr. Dennett’s enduring attraction.

Whereas he admitted that lots of the questions he raises in his work “cannot yet be answered,” wrote the reviewer, Mr. Dennett “argues that putting the right questions is a crucial step forward.”

Kellina Moore contributed reporting.