A nondescript locker in a Decrease Manhattan storage middle is a portal to a New York Metropolis nonetheless affected by crack, AIDS and rampant crime.

A drug person squats for a repair in a squalid Manhattan heroin den. A person carrying a Savage Riders biker gang jacket holds a yawning child. A baby straddles a stripped bicycle on a trash-strewn avenue in Spanish Harlem.

Not all the things is bleak. There’s a pig roasting on a spit in an deserted Brooklyn lot. A smiling, bikini-clad bodybuilder flexes subsequent to a Hasidic rabbi on a Queens seaside.

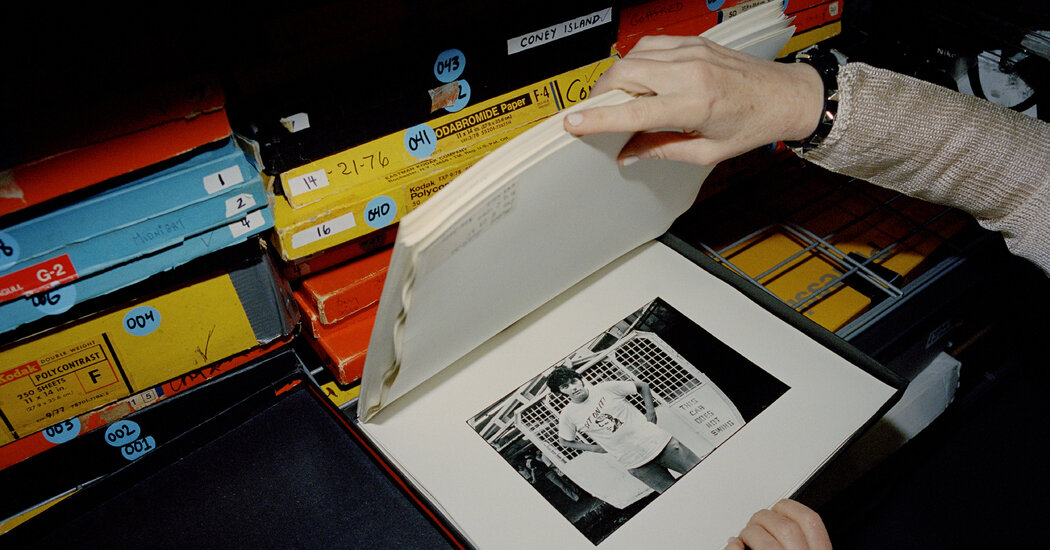

These pictures and numerous others are crammed into a whole lot of packing containers left behind by the heralded avenue photographer Arlene Gottfried, who skilled her unflinching lens on New York’s much less heralded neighborhoods through the Nineteen Seventies and Eighties.

The archive, whereas valued in images circles for each its creative integrity and documentation of underrepresented neighborhoods, had remained in limbo and disarray since Ms. Gottfried’s death in 2017 at age 66 from issues from breast most cancers.

However now, it appears, it’s being saved.

Ms. Gottfried left the archive to her brother, the comic and actor Gilbert Gottfried, and to their sister, Karen Gottfried, a retired schoolteacher. Earlier than she died, the photographer requested her brother and his spouse, Dara Gottfried, to protect her work to make sure her legacy.

However Mr. Gottfried, who relied on his spouse to pack his suitcases when touring to gigs, was not about to kind by means of his sister’s tens of hundreds of pictures on slides, negatives and prints.

Then, not lengthy after Arlene’s demise, he fell unwell himself and died in 2022 at 67.

Final 12 months, Dara Gottfried mentioned, she lastly started having the photograph assortment digitized and arranged, with the assistance of Eryn DuChene, a younger photographer.

As soon as full, she mentioned, she is going to decide whether or not it is going to go to a museum or a purchaser prepared to maintain the work accessible to the general public.

“Arlene wanted her legacy kept alive in museums or shows or galleries,” Dara Gottfried mentioned throughout a current go to to the locker. “Gilbert and I wanted to honor her wishes to have her work shared with the world, so it could live on forever.”

Mr. DuChene has been digitally scanning photographs from the packing containers piled on cupboards and cabinets in a storage unit the dimensions a WC.

He pulled out crates of outdated movie cameras — Ms. Gottfried by no means switched to digital images — and yellow Kodak packing containers full of toilet portraits of clubgoers from the disco period. In one other field, tattooed lovers embrace on the road. There isn’t a series retailer or cell phone to be seen within the pictures.

Over time, her output amassed in her studio house within the Westbeth homes, the backed artists’ colony within the West Village that was as soon as dwelling to the photographer Diane Arbus, to whom Ms. Gottfried has been in contrast.

“It sat in her apartment like an elephant in the room,” mentioned Ms. Gottfried’s gallerist, Daniel Cooney. “She didn’t want to deal with it. She didn’t know where to start.”

Sean Corcoran, senior curator of prints and images on the Museum of the Metropolis of New York, known as Ms. Gottfried’s archive “a novel and essential assortment, with each creative worth and historic and social relevance to a second in time in New York Metropolis.”

“What’s at stake,” he said, “is choosing the right place for it to go because the material could either wallow in obscurity or, at the right home, be recognized as the important body of work that it really is.”

While the Gottfried archive would not necessarily command a price like those of Robert Mapplethorpe or James Van Der Zee, two other New York photographers whose archives brought sizable sums, it could attract offers from top institutions, he added.

When Ms. Gottfried was growing up in Brooklyn, her father gave her an old camera, which she used to begin shooting candid street scenes and portraits of strangers.

“We lived in Coney Island, and that was always an exposure to all kinds of people, so I never had trouble walking up to people and asking them to take their picture,” she told The Guardian in 2014.

When the family moved to Crown Heights, a teenage Arlene began shooting her neighbors, and went on to capture daily life and local characters in similar neighborhoods on Manhattan’s Lower East Side and in Spanish Harlem.

“It was a mixture of excitement, devastation and drug use,” she told The New York Times in 2016. “But there was more than just that. It was the people, the humanity of the situation. You had very good people there trying to make it.”

She studied photography at the Fashion Institute of Technology in Manhattan and did commercial photography for an advertising agency in the mid-1970s. Then her freelance career saw her work published in The Times, The Village Voice, and Fortune and Life magazines.

Over the years, the city became safer, more gentrified and, to Ms. Gottfried, less visually interesting.

“Arlene liked the old New York before it got fancy and rich,” Karen Gottfried, her sister, said. “There were honestly a lot more oddballs around, everyone dressed with individuality and she liked all that. She didn’t like fancy. She liked the funky stuff.”

Ms. Gottfried’s work started attracting a wider curiosity later in her life. Her work was displayed in books and gallery exhibits, together with a very profitable one in 2014 at Mr. Cooney’s gallery in Chelsea.

“She was shocked and grateful that people were buying her work,” Mr. Cooney said. Her prints began fetching $5,000 each, an impressive amount for street photography, he said.

Mr. Cooney organized another Arlene Gottfried show in 2016 and then three more after her death. Dara Gottfried said that a curator has selected prints from the locker for a show in Germany in March. A photography center in France is also selecting photos for a solo show.

“She didn’t get nearly enough attention during her lifetime,” Mr. Cooney said.

Mr. Gottfried beloved and inspired his sister’s photograph work. She was featured in “Gilbert,” a 2017 documentary about him.

“How her eye captures people, and how she touches them, that’s hard to explain,” he told The Guardian in 2014.

Ms. Gottfried also encouraged her brother’s artistic interests, both as a talented sketcher and performer. Mr. Gottfried, five years younger than her, entertained the family with jokes and imitations. His interest in standup comedy blossomed in his teens after his sisters took him to an open-mic night in Greenwich Village.

“They had a mutual respect for each other — they supported each other,” said his wife, Dara Gottfried. “I think there’s a lot of parallel between them, the way they grew up and looked at the world. Both were real artists and cared about the art and not the glitz and glamour of show business.”

Adam Reid, a writer and director who was friends with Mr. Gottfried, said the siblings’ similar artistic expression was largely formed during their austere childhood.

“They processed the trauma of growing up in poverty during some of the city’s darkest eras and both found a way to find light in the darkness and turn their pain into bold, creative expression,” he said.

As adults, Arlene Gottfried continued to live near her brother in Manhattan and regularly met him for breakfast. Mr. Gottfried’s fame sparked a running joke among her friends.

“Instead of saying, ‘How are you?’ they’d say, ‘How’s your brother?’” Karen Gottfried recalled. “She loved that.”

When Arlene began declining from cancer, Mr. Gottfried accompanied her through her treatment and kept up her spirits with his humor.

She never married or had children and remained focused on her photography, Karen Gottfried said.

“It wasn’t lucrative, but she did it for love of it,” she said. “She sacrificed a lot for her art. She stuck with it and didn’t sell out.”