Individuals in Lagos, Nigeria’s largest metropolis, are hardly shy. The stereotype runs towards boisterousness, worn as a degree of satisfaction. However when the artist and poet Precious Okoyomon recorded interviews with some 60 metropolis residents in January for an artwork challenge, the bizarre questions — like “Who was responsible for the suffering of your mother?” — proved disarming.

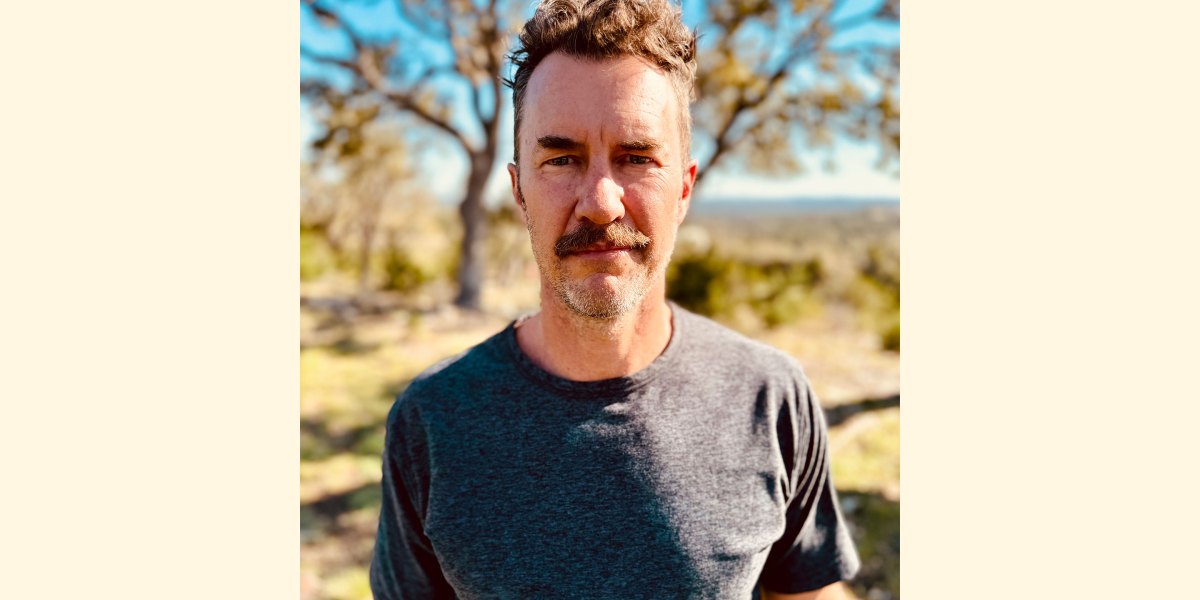

Okoyomon is predicated in Brooklyn, however lived in Lagos as a baby and nonetheless visits there steadily. The artist was amassing materials for a sonic and sculptural set up that will likely be offered within the Nigeria Pavilion at this year’s Venice Biennale. The occasion, one of many artwork world’s most essential, opens for previews subsequent week and to the general public on April 20.

Okoyomon’s steel-framed construction, erected in a courtyard, imagines a sort of radio tower, decked with bells and colonized by creeping vines. Movement sensors on the tower activate a soundtrack: It is going to play within the courtyard and in addition on-line, for anybody to tune in. It mixes poems by Okoyomon with music and passages from these interviews, whose respondents vary from fellow artists to “strangers, someone’s cook, someone’s auntie,” Okoyomon stated.

After some cautious first reactions to the intimate 12-question protocol (tailored from one other poet, Bhanu Kapil), the conversations grew susceptible and actual, Okoyomon stated. The ensuing sound piece, was “a kind of speaking in tongues,” as if tapping the unconscious of town, Okoyomon added.

Okoyomon is a Venice veteran: In 2022, the artist offered a major installation in the Biennale’s main exhibition. However this yr Okoyomon is likely one of the eight lauded artists to characterize Nigeria within the nation’s second-ever Venice pavilion — one in every of nonetheless comparatively few African displays on the Biennale, and one of the vital bold in idea and scale.

Titled “Nigeria Imaginary,” the pavilion fills a semi-restored palazzo within the Dorsoduro district with initiatives that forged an indirect however pointed have a look at historical past. One is Yinka Shonibare’s exacting clay replicas of 150 of the Benin Bronzes {that a} British expeditionary drive plundered in 1897; they accompany a bust of the raid’s British commander painted in batik patterns and positioned in a vitrine, a sort of symbolic restitution awaiting the true factor.

In essentially the most modern reference, a sculpture by Ndidi Dike manufactured from 700 police-grade batons, along with pictures from mass protests against Nigerian police violence in 2020 — and their bloody repression — hyperlink common struggles within the nation to the Black Lives Matter motion in the US, Britain and Brazil.

Different initiatives — by Tunji Adeniyi-Jones, Onyeka Igwe, Abraham Oghobase, Toyin Ojih Odutola and Fatimah Tuggar — span drawing and portray, video and pictures, even A.I. and augmented actuality. They counsel recent methods for Nigerians, and in addition the world, to consider the nation — a behemoth of some 220 million individuals that’s usually dismissed as a spot of disaster or corruption.

Thus Ojih Odutola’s charcoal and pastel works on linen stage free-spirited, gender-flexible characters in a setting impressed by Mbari homes, once built for ritual in southeastern Nigeria; a linked reference is the Mbari Club, which gathered Nigerian artists and writers within the Nineteen Sixties. “I wanted the space to exist very open and free,” stated Ojih Odutola, who is predicated in New York and Alabama, of the suite of drawings. In her imagined Nigeria, she added, creativity “is safe; it has room to roam; it has the right to change, to be mercurial.”

Adeniyi-Jones, who was raised in Britain and now lives in Brooklyn, has produced an overhead portray influenced by Nigerian Modernist artists and Italian decorative custom that may hold under the palazzo ceiling.

Oghobase, who works in pictures and installations and is newly dwelling in Canada, examines useful resource extraction in northern Nigeria by means of unique and archival pictures plus diagrams from a classic mining treatise.

Tuggar, who teaches on the College of Florida, considers the common-or-garden calabash gourd — a fruit with myriad conventional makes use of in West Africa, from consuming vessel to musical instrument to fishing float — in an set up that makes use of augmented actuality to visualise alternate options to plastics and different shopper merchandise.

And Onyeka Igwe, who lives in Britain, researched the Nigerian Film Unit, which produced movies throughout the colonial interval. Its archive in Lagos turned uncared for, and when Igwe visited, she stated, “there were lots of stopped clocks; it was full of rotting reels.” Igwe’s movie “No Archive Can Restore You,” research this derelict house; a sound set up of speeches, poems and choral music then fills the room in a different way — hinting that colonial archives could also be extra burden than useful resource, crowding out different methods to attach with historical past.

To arrange a nationwide pavilion on the Biennale is itself a sort of historical past intervention. The pavilion system dates to the early Twentieth century and maps a hierarchy. There are everlasting pavilions owned by round 30 principally rich international locations within the gardens the place a lot of the Biennale takes place, many with distinguished structure. Different international locations current their pavilion in one-off areas, some wedged into the Biennale’s different main exhibition advanced within the Arsenale, others scattered round city.

The African presence has been slender and uneven. (Tales abound of slapdash pavilions underfunded by governments or handed to doubtful international impresarios.) However not too long ago, it has grown in numbers and rigor. In 2013, Angola gained the Golden Lion for finest pavilion. Nigeria’s first and solely prior pavilion — a solid but smaller affair than this yr’s — got here in 2017. In 2019, Ghana offered a star-studded show together with El Anatsui and Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

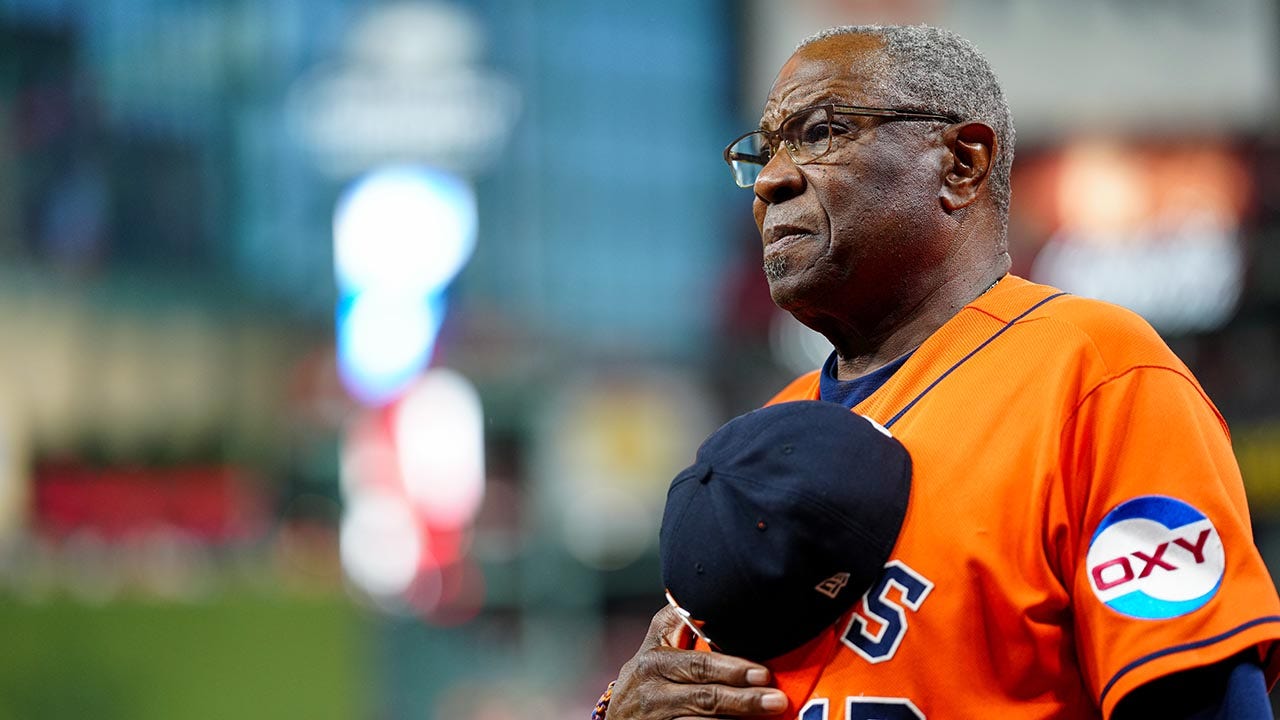

This yr 13 African countries are presenting pavilions, up from 9 in 2022. The paucity is comprehensible given extra pressing financial improvement priorities, stated Phillip Ihenacho, the director of the Museum of West African Art, often called MOWAA, now underneath development in Benin Metropolis, Nigeria. “The decision to do anything in Venice is a difficult one,” Ihenacho stated. “You have to ask yourself, ‘Why spend money on something which could be regarded as a vanity project?’”

However a powerful pavilion sends a message, whether or not from a authorities signaling cultural funding, or, in Nigeria’s case this yr, from personal backers. Though commissioned by the Nigerian authorities, as Venice guidelines require, the pavilion has been organized by MOWAA. The pavilion’s high funder is Qatar Museums; different supporters embody galleries representing the artists, and Nigerian and international corporations and collectors.

For MOWAA, whose inception was linked to the fraught prospect of many Benin Bronzes returning to Africa, the pavilion conveys a dedication to modern artwork, Ihenacho stated. With the primary constructing due for completion late this yr, the plan is to carry the Venice present to Benin Metropolis — presumably after one or two worldwide stops — because the inaugural exhibition, he stated.

On a sizzling, dusty Thursday in February, Aindrea Emelife, the pavilion’s curator, who will even lead MOWAA’s fashionable and modern division, was crisscrossing Lagos, finalizing issues. She met with Dike, the one pavilion artist dwelling full-time in Nigeria. Although all of them have Nigerian roots, the others both grew up abroad, or moved away from Nigeria in some unspecified time in the future.

Emelife herself grew up in Britain. Although she anticipates criticism that the present favors overseas-based artists, migration — and generally return — are a part of the Nigerian expertise, she stated. “People are always leaving, and that’s important to articulate with presenting Nigeria as a place.”

Moreover, she added: “I don’t think you can remove yourself intrinsically from Nigeria.” Certainly, if something, pavilion artists are deepening their ties. Shonibare, as an example, opened a Nigerian foundation in 2019 that operates two residency facilities and a sustainable farm.

Emelife’s subsequent cease was the house of an area collector to borrow some letters by Ben Enwonwu, an essential Nigerian Modernist painter, for a vitrine presentation of paperwork from the Nineteen Sixties and Seventies within the pavilion. Many artists in that interval had been invested in connecting the Western canon with native aesthetics, tradition and historical past.

“It’s important that this is not presented in isolation as a new moment,” Emelife stated of the modern work within the pavilion. “I’ve met people who had no idea there was a Modernist period in Nigeria.” (Her concern dovetails, because it occurs, with the Biennale’s main exhibition this yr, which the curator Adriano Pedrosa has loaded with Twentieth-century Modernists of the International South.)

With “Nigeria Imaginary” because the pavilion theme, Emelife makes a scholarly reference — to sociological theories of nationhood or to the “imaginary” within the work of the psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, or the tales and illusions we inform ourselves to search out construction in our environment. In Nigeria, the place considerable dysfunction has develop into normalized — as an example, the widespread use of residence turbines and inverters to deal with the incessant energy outages — that idea appears apt.

However the totally different initiatives within the present additionally make guests privy, if not directly, to a nationwide pastime: diagnosing the nation’s issues. “The trouble with Nigeria,” Chinua Achebe wrote in a 1983 essay by that title, “has become the subject of our small talk in much the same way as the weather is for the English.” (His evaluation in a nutshell: dangerous management.)

That behavior stays. “Everyone’s the minister of something!” Emelife stated. “There’s so much discussion about what Nigeria needs, or Nigeria should be like.” Her want for the exhibition, she stated, was to immediate extra expansive dreaming. “It will hopefully be energizing, by being honest, but also energizing, by being utopic,” she stated. In spite of everything, she added, “Even when we’re critical, we’re critical because we’re optimistic about what a great place it could be.”

Dike, the Lagos lifer and detractor of police violence, agreed. “There’s always these not-so-positive discussions about Nigeria,” she stated. “But this is a very dynamic cultural catalyst and hub for the continent — and the world. It’s about time we give Nigeria its due.”