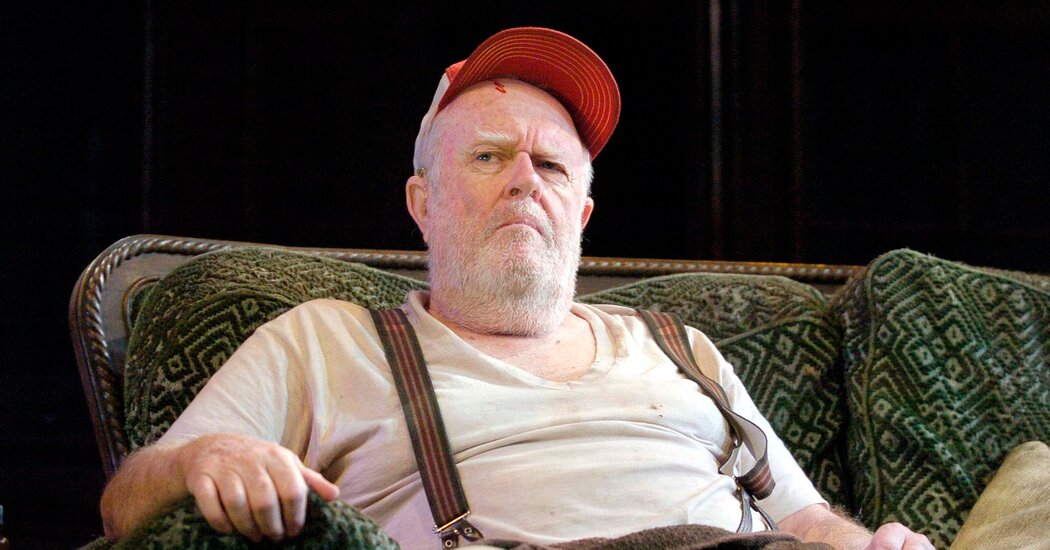

M. Emmet Walsh, a paunchy and prolific character actor who was known as “the poet of sleaze” by the critic Roger Ebert for his naturalistic portrayals of repellent lowlifes and miscreants, died on Tuesday in St. Albans, a small metropolis in northern Vermont. He was 88.

His demise, in a hospital, was introduced by his supervisor, Sandy Joseph.

Probably the most enduring reward Mr. Walsh obtained additionally got here from Mr. Ebert: He coined the Stanton-Walsh Rule, which asserted that “no movie featuring either Harry Dean Stanton or M. Emmet Walsh in a supporting role can be altogether bad.”

In “Straight Time,” a 1978 movie that includes each Mr. Stanton and Mr. Walsh, Mr. Walsh performed a patronizing parole officer to Dustin Hoffman’s teetering ex-con. Mr. Walsh’s efficiency caught the attention of two brothers who aspired to be auteurs and have been writing their first feature-film script.

The unknown Joel and Ethan Coen wrote the pivotal character of a detective in “Blood Simple” for Mr. Walsh. To their shock, and regardless of providing little extra in compensation than a per diem stipend, he accepted the position.

Reviewing “Blood Simple” for The New York Occasions in 1984, Janet Maslin mentioned that Mr. Walsh had captured “a mischievousness that is perfect for the role.” Writing in Salon on the event of the discharge of Janus Movies’ digital restoration in 2016, Andrew O’Hehir praised Mr. Walsh’s portrayal of a “sleazy, giggly and profoundly disturbing private detective.”

On the set, he took pleasure in hazing the neophyte administrators. “Let’s cut this sophomoric stuff, it’s not N.Y.U. anymore,” Joel Coen recalled him saying, in response to a Times article in 1985. “One time I asked him to do something just to humor me, and he said, ‘Joel, this whole damn movie is just to humor you.’”

After the movie’s essential success — Mr. Walsh gained the primary Unbiased Spirit Award for greatest efficiency by an actor — the Coen brothers introduced Mr. Walsh again for a cameo of their second film, “Raising Arizona.”

Additionally in that film, along with Nicolas Cage and Holly Hunter, was John Goodman, who went on to grow to be a Coen Brothers common — whereas Mr. Walsh didn’t. With Mr. Goodman on board, Mr. Walsh mentioned in an interview for the Janus Movies version of “Blood Simple,” “their casting needs didn’t involve me anymore.”

Michael Emmet Walsh was born on March 22, 1935, in Ogdensburg, N.Y. His father, Harry Maurice Walsh Sr., was a customs agent on the Vermont-Quebec border; his mom, Agnes Katherine (Sullivan) Walsh, ran the family.

Mr. Walsh was raised in rural Swanton, Vt., and attended close by Clarkson College in northern New York State, incomes a bachelor’s diploma in enterprise administration whereas dabbling in stage productions.

“I had a good faculty adviser up there who said, ‘Why wait to be 40 to wonder whether you should have been an actor? Get rid of it now, or find out!’” Mr. Walsh mentioned in a 2011 interview on the Silent Film Theater in Los Angeles. “So I went to New York.”

He was schooled in appearing on the American Academy of Dramatic Arts and likewise, much less formally, in New York theaters. Unable to afford tickets, he would slip in amid the gang at intermission.

“There was always an empty seat. And you see everything!” he mentioned. “I saw Annie Bancroft do ‘Miracle Worker’ with Patty Duke, probably 40 times; ‘Raisin in the Sun’ with Sidney Poitier. And I just watched them.”

Deaf in his left 12 months since a mastoid operation when he was 3 years outdated, and with a clipped Vermont accent, Mr. Walsh mentioned, “It was obvious I wasn’t going to do Shaw and Shakespeare and Molière — my speech was simply too bad.”

“People go and try to become the next Pacino,” he continued, “or the next Meryl Streep or something — they don’t want that. They want something new, something different — they want you! And actors have a hard time figuring that out. So I had to figure out who I was and what I could do, that no one else could do.”

He performed in regional theaters throughout the Northeast for most of a decade, then made his Broadway debut in “Does a Tiger Wear a Necktie?” (1969), starring Al Pacino.

A few parts in television commercials led to an uncredited role in “Midnight Cowboy” that same year. He then landed the part of the irate and incomprehensible Group G Army sergeant in Arthur Penn’s screen adaptation of Arlo Guthrie’s song “Alice’s Restaurant.”

Then came about 120 movie roles over the next five decades, and even more television parts. The critics took notice: He was a “cynical small-town sportswriter” in “Slap Shot” (1977), a “bonkers sniper” in “The Jerk” (1979), a “hard-drinking, sleazy and underhanded police veteran” in “Blade Runner” (1982) and an “unsympathetic swimming coach” in “Ordinary People” (1980).

In a 2011 profile for L.A. Weekly, the critic Nicolas Rapold called Mr. Walsh “a consummate old pro of the second-banana business.”

“My job is to come in and move the story along,” he said in the Silent Movie Theater interview. “The stars don’t do the exposition … So I come on with Redford or Newman or Dustin or somebody, and I throw the ball to them, and they throw it back, and it starts to become that tennis match, back and forth, and that’s what makes the dynamics of the whole thing.”

“And I’m driving the movie forward,” he added. “They don’t want an Emmet Walsh. They want a bus driver. They want a cop. They don’t want an Emmet Walsh cop. I just try to sublimate myself and get in there and do it.”

Mr. Walsh had confidence in his ability to deliver, and he knew how valuable that was to harried filmmakers. “You’re casting something, and you’ve got 12 problems; if they’ve got me, they only have 11 problems.”

He said that directors sought him out for his ability to elevate subpar material. “They’d say, ‘This is terrible crap — get Walsh. At least he makes it believable.’ And I got a lot of those jobs.”

Reviews reflected that. Mr. Walsh was often singled out in otherwise forgettable films — for a “good individual performance” in “The Fish That Saved Pittsburgh” (1979), as a “dependable talent” in “The Best of Times” (1986).

That is not to say he never had a miss; his performance in “Wild, Wild West” (1999) prompted Mr. Ebert to deem the Stanton-Walsh Rule “invalidated.”

In 2018, Mr. Walsh’s “Blade Runner” co-star, Harrison Ford, inducted him into the Character Actor Hall of Fame. At that same ceremony, he was honored with the Chairman’s Lifetime Achievement award.

He continued appearing lately, together with within the 2019 film “Knives Out” and in a 2022 episode of the Showtime sequence “American Gigolo.”

Mr. Walsh leaves no immediate survivors. He lived in St. Albans and in Culver City, Calif.

Of his own body of work, he told the comedian Gilbert Gottfried in a 2018 episode of his podcast: “There’s a lot of stuff out there. They’re not all ‘Hamlet.’ But I’m not ashamed of any of it.”

“The parts are all your children,” Mr. Walsh said in a 1989 interview with the trade newspaper Drama-Logue. “They’ll be my epitaph when they throw in that last shovelful of dirt.”

Alex Traub contributed reporting.