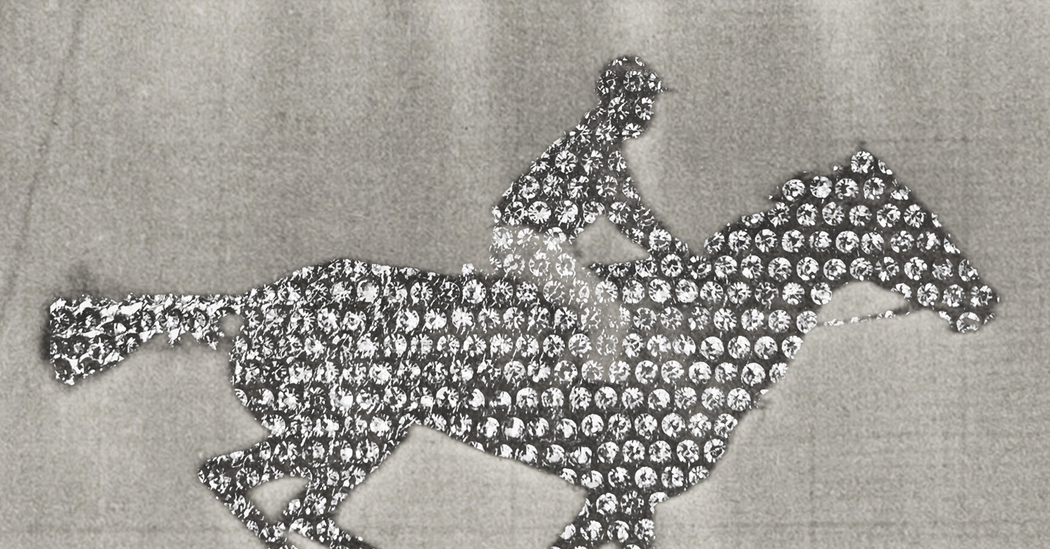

Beyoncé launched a genre-bending nation album, “Cowboy Carter,” final week. After listening to it in all of the requisite settings — on a stroll, in a automotive and on a airplane — I lastly perceive what Beyoncé, a notoriously enigmatic pop star, needs to say to the world. She needs to be greater than standard. She needs to be legendary. However first, she isn’t by means of taking everybody who has doubted her to the woodshed.

In outlaw nation custom, “Cowboy Carter” settles scores with haters and with historical past. Beyoncé has trilled, growled, marched, stepped, sweated and sung her coronary heart out for nearly 30 years. It’s, this album argues, together with the others in her in-progress three-act “Renaissance” oeuvre, time for a bit of respect, for Black artists typically but additionally for her particularly.

Simply by being Black, a lady, standard and impervious to nation music’s gatekeepers, Beyoncé has made a political album. Puzzling over who’s nation sufficient to sing love songs to wheat fields and large vehicles solely appears prosaic. Massive Nation — the Nashville-controlled, pop-folk music that commodifies rural American fantasies — is the cultural arm of white grievance politics. In 1974, President Richard Nixon described the style as being “as native as anything American we could find.” That will need to have been a shock to precise Native People. However the message was not for them. It was for the white Southern voters Nixon wanted to win over amid large resistance to Black enfranchisement. Right this moment’s Republican Celebration continues that custom. Embracing nation music is a loyalty take a look at for conservative politicians and right-wing pundits whose profession ambitions align with white id politics. Beyoncé singing nation music on this political local weather was all the time going to trigger a stir.

I went into this album launch anticipating, like many cultural critics, that the largest query can be: Is it nation? She is from Texas, which needs to be sufficient. She additionally has that voice — not her singing voice, however her talking voice. It’s molasses sluggish and heavy-toned like Southern humidity. Doubting Beyoncé’s nation bona fides is like insisting that the realest People can solely be present in small-town diners. It’s a handy shorthand for dismissing individuals you’d slightly not take into consideration.

“Ameriican Requiem” is a strong opening monitor that addresses anybody who reductions Beyoncé’s Southern résumé. Massive Nation produces a stylized set of tropes that artists, producers and advertising executives slather on high of meter and rhythm. In good palms, these tropes could be signposts for a street journey by means of a sonic postcard. In lazy palms (and so most of the palms are lazy lately), they’re paper dolls of low-cost sentiment. You identify your small city for legitimacy. You gesture to your loved ones for kinship to rural America’s fictive household tree. Then you definately sprinkle in your proprietary mixture of vehicles, canines, sunsets and beer for distinction.

Beyoncé takes on these tropes in “Ameriican Requiem.” Her id provides them weight. She sings that her small-town roots are by means of “folks down in Galveston, rooted in Louisiana.” Because the “grandbaby of a moonshine man” she has a proper to sing the white man’s blues, as a result of as a Black Southern lady she will be able to legitimately declare the blues. Turning again to the viewers of doubters, she sings: “Used to say I spoke ‘too country’/And the rejection came, said I wasn’t country ’nough/Said I wouldn’t saddle up, but/If that ain’t country, tell me what is?” Given the pedigree she has simply laid out, the one sincere reply is that nation music is every part she sings about minus the Black lady singing it.

The track appears to be aimed squarely on the reception Beyoncé received on the 2016 Nation Music Affiliation Awards. She carried out with the Chicks for a style mash-up of her first nation report, 2016’s “Daddy Lessons.” The second was heavy with signification. The Chicks have been the proverbial prodigal son — white feminist nation icons, solid out for his or her politics, returning to the fold. Beyoncé, the mega pop star, introduced the sheen of Black excellence and crossover attraction. The duet ought to have led to a multiracial kumbaya for a notoriously homogeneous trade. As a substitute, the viewers of just about all white report executives, nation singers, radio programmers and Nashville elites regarded alternately surprised and dismayed all through the efficiency. A few of them yelled racist feedback on the stage. Viewers complained it was not actual nation. Black artists have lengthy complained — typically silently, for concern of being blackballed — that the nation music trade is hostile to them. The C.M.A. debacle proved their level. Massive Nation decides what’s nation by policing who is nation.

“Cowboy Carter” is a Rosetta Stone for the hidden racial politics in nation’s aw-shucks exclusion that the C.M.A. efficiency placed on show. Beyoncé mocks the thought of style and by extension these obsessive about its boundaries. In an interlude, she makes use of a recording of Linda Martell coyly questioning the misleading simplicity of musical genres to make a deft critique. Martell is usually credited as fashionable nation’s first commercially profitable Black lady artist. Her album “Color Me Country” charted in 1970. Take a look at how lengthy the sanctity of style has been used to erase artists like me, Beyoncé appears to say.

In one other interlude Beyoncé turns up the warmth, asking who has the facility to transcend genres. The sound of a radio dial flips by means of songs, together with Chuck Berry’s 1955 basic “Maybellene.” The track helped inspire a younger white man named Elvis Presley to make rock ’n’ roll music. When white artists inject themselves into different cultures’ genres, together with blues and soul and R. & B. and rock ’n’ roll, they grow to be legends. Why, Beyoncé asks, are Black artists beholden to style’s dictates?

Beyoncé solutions that query with layered textual references, interludes, samples and copious visible artwork that gestures towards the apparent reply (uh, racism). This creative tease has grow to be a trademark of Beyoncé’s post-“Lemonade” output. Typically the gestures are too heavy for her variable songwriting to hold. They work on “Cowboy Carter” as a result of nation music is so proof against the obvious questions on its politics that even a gesture goes off like a bomb.

If nation music is about being from the South, she playfully rejoins, why isn’t Houston’s gritty “chopped and screwed” type sufficiently nation? If nation music is about homicide ballads that romanticize the darkest, most transgressive human needs, why isn’t it romantic when a Black lady is the one doing the killing? If nation music is about defending fireside and residential for the love of lady, she taunts, why aren’t her stoic Black father and her younger daughter an American household value combating for? The one approach for Massive Nation to reply these questions actually is to speak about race and gender, racism and sexism, historical past and energy. However these topics are all verboten.

That sucks for nation music. The style’s most profitable artists development towards apolitical pablum as a result of they’ll’t or gained’t say something fascinating. Their loss is that this album’s acquire. Beyoncé can ask these questions of nation music as a result of she shouldn’t be an insider. As one of many greatest stars on the earth, she will be able to take the warmth that comes with disrupting nation’s white noise drawback. When nation music performers are largely white, the style can fake it’s one large household. That’s straightforward to faux when it controls who is taken into account household. However the sound turns into inbred. New blood highlights the distinction. Nation music’s self-consciousness about its standing as actual or cool music is its personal fault. You can not create artwork with out getting one thing extra substantial than mud in your tires.

Beyoncé shouldn’t be afraid to get soiled in her creative decisions. Even after they don’t work, they aren’t boring. Her interpretation of Dolly Parton’s “Jolene” is an instance. The track is among the nice folks songs of the twentieth century, written and carried out by a star who has grow to be one thing of a secular saint. A canopy would have been straightforward. As a substitute, Beyoncé exhibits creative imaginative and prescient by selecting to not remake the track however to reinterpret it.

Her model is forgettable, however her option to interpret it by means of her personal id is essential. The unique, from 1973, weeps with vulnerability. Parton is begging redheaded Jolene to not take her man. This did one thing actually highly effective for the time. It ascribed the stability of energy in a heterosexual marriage to not the husband however to a different lady, interesting to her ethical compass as an alternative of judging her unethical flirting. That vulnerability works as a result of Parton represented the sort of lady who was allowed to be susceptible. Much more, a white lady from the Appalachia area of america within the Nineteen Seventies wanted her man, not only for love but additionally for financial safety. When Parton asks Jolene to not take her man, she’s asking Jolene to not take the very roof over her head. However Beyoncé shouldn’t be combating for her financial survival. She is combating for her standing as a rich spouse. That may be a place of social dominance over different girls. Her model of the track sounds extra like a wealthy spouse’s “Fist City” than a down-on-her-luck housewife from a poor city as a result of Beyoncé is aware of who she is. That’s integrity.

I fearful about that songwriting integrity when this album was introduced. Irrespective of the way it sounded, a Beyoncé nation report can be culturally necessary. However for it to be good in a country-folk soundscape, the album would even have to speak to the viewers.

At its greatest, nation music is a lyrically pushed storytelling style that elevates the mundane to the common. Beyoncé’s songwriting has been spotty, even when her conceptual imaginative and prescient has been distinctive. I don’t suppose she has ever had a secular expertise in her life, in order that’s a nonstarter. Much more difficult is that nearly a decade in the past, Beyoncé mostly stopped talking to her viewers. Hardly ever giving interviews is a perk of being a mega movie star. Nonetheless, it has created a vacuum. We all know Beyoncé makes hits and wonderful visuals, however can any of us say that we all know what Beyoncé needs?

Enjoying with the political fault traces of style opened up Beyoncé’s storytelling. On “16 Carriages,” she makes a transparent creative assertion that echoes within the silence she has created. “For legacy, if it’s the last thing I do/You’ll remember me ’cause we got something to prove.” Legacy requires legibility. It’s virtually crucial for a pop artist to do a bit greater than gesture towards the textuality in her work if she needs that textual content to be legible. When she doesn’t, the viewers fills within the gaps. They faithfully decode her gestures (particularly her standard visuals) on social media. That’s good fan service in a hypercompetitive consideration financial system. It additionally buffers Beyoncé from the blowback that comes from saying clearly who she is and what she needs to say. However for somebody fixated on legacy, letting followers litigate your creative assertion on this fragmented media tradition results in a chaotic message.

Beyoncé is finally the creator of her legacy, not the Grammys or the C.M.A.s or many of the gatekeepers at this level. However she must do greater than gesture to her legacy for us to assist her fulfill it.

I’m satisfied that the suitable approach to consider this album is thru the lens of legacy. “Renaissance” was labeled Act One and this album is Act Two. Hypothesis abounds {that a} third act will full a three-album quantity of Black musical reclamation. As a substitute, with the style deconstruction of “Cowboy Carter,” the thought of an album trilogy appears like a playbook for cementing Beyoncé’s legacy.

One other historic trilogy involves thoughts. Stevie Marvel’s Nineteen Seventies run of albums embrace among the most necessary standard music ever recorded. Three of them — “Innervisions” (1973), “Fulfillingness’ First Finale” (1974) and “Songs in the Key of Life” (1976) — gained Grammy Awards for album of the yr. These albums have been the uncommon mixture of commercially profitable and critically acclaimed. They have been additionally a fastidiously constructed inventive assertion. Stevie Marvel was a toddler star, a prodigy. He made profitable pop music. The albums he launched within the Nineteen Seventies marked his transition to Stevie Marvel, the legendary artist. He additionally performed with style, most notably by mainstreaming the then-novel synthesizer in standard music. He may nonetheless pen a basic love track, however he additionally turned his inventive imaginative and prescient to the politics of our mundane lives. Alongside the best way, he did greater than gesture to his artwork. He guided the general public’s musical tastes by means of his evolution.

On reflection, Beyoncé started her personal break from youthful stardom with “Lemonade” in 2016. Though that album focuses on a wedding that I might frankly be comfortable to listen to much less about, it’s a definitive break from her pop-lite picture. On “Renaissance,” Beyoncé expanded her breadth of sounds a lot in the identical approach Marvel did with the synthesizer. (Marvel played harmonica on Beyoncé’s model of “Jolene.”) On “Cowboy Carter” she slows down sufficient to inform a narrative that each one listeners — shut or informal — can obtain.

I’m greater than superb with signing on to the Beyoncé legacy undertaking, which guarantees to reclaim Black artwork throughout genres which have erased Black contributions. That’s noble. However she has additionally labored actually onerous to raise a really particular period of a younger feminine singer’s profession — that sanitized expression of girlhood — into one thing extra expansive. She selected to do this by means of Black artwork, leaning into her Southernness, her accent, her decrease vocal vary, as an alternative of selecting to grow to be a extra palatable post-racial pop star. On this album she makes a case for why, as an alternative of merely embodying the latent politics of pop, home and nation, she’s selecting to remodel them into one thing else. The result’s an eminently pleasurable album with some imperfections however a sign of what could possibly be doable if extra artists comply with her lead.

Beyoncé can’t sing authentically about rising up poor or making ends meet. (She grew up higher center class.) However she will be able to reinscribe a style’s latent politics. When she sings one other style in her physique, she interprets that style by means of her id. The consequence could make you dance, however it could actually additionally make you reckon together with your complicity in that style’s policing of who’s and isn’t legitimately American.

Reinscribing pop music’s historical past on a Black feminine Southern artist expands a imaginative and prescient of America’s cultural politics. It isn’t multiracial within the facile sense. Beyoncé’s ambition is to proper the crooked room of American pop music, one which has tilted towards hidden racial politics and commodified inclusivity. She might not be innovating with new devices or a singular new sound, as earlier pop music legends have finished. She doesn’t have to. She has a singing voice that may be a superb instrument. If she would flip her talking voice to the viewers and narrate her imaginative and prescient, the general public work of reimagining style may grow to be the legacy undertaking she so clearly needs.

Tressie McMillan Cottom (@tressiemcphd) turned a New York Instances Opinion columnist in 2022. She is an affiliate professor on the College of North Carolina at Chapel Hill College of Info and Library Science, the creator of “Thick: And Other Essays” and a 2020 MacArthur fellow.

Supply {photograph} by Adrienne Bresnahan through Getty Photos.

The Instances is dedicated to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to listen to what you concentrate on this or any of our articles. Listed below are some tips. And right here’s our electronic mail: [email protected].

Comply with the New York Instances Opinion part on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, WhatsApp, X and Threads.