Rodino Sawan stepped into the wire harness and dug his toes into the muddy monitor that threads the sweltering plantation. He pushed ahead, straining towards the cargo trailing behind him: 25 bunches of freshly harvested bananas strung from hooks hooked up to an meeting line.

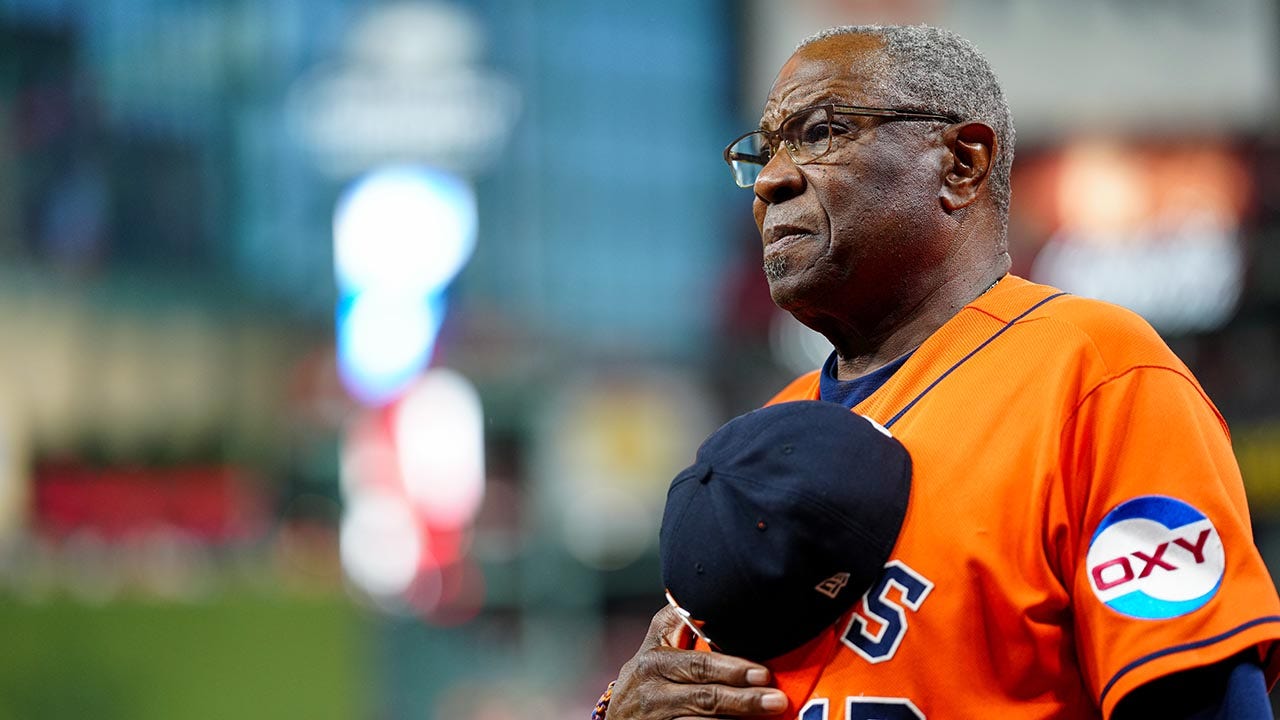

Six days every week, Mr. Sawan, 55, a father of 5, tows batches of fruit that weigh 1,500 kilos to a close-by processing plant, usually as planes buzz overhead, misting down pesticides. He returns house with aches in his again and day by day wages of 380 Philippine pesos, or about $6.80.

Sooner or later final 12 months, the plantation bosses fired him. The subsequent day, they employed him again into the identical function as a contractor, reducing his pay by 25 p.c.

“Now, we can barely afford rice,” Mr. Sawan stated. Nonetheless, he continued to indicate up, resigned to the fact that, on the island of Mindanao, as in a lot of the agricultural Philippines, plantation work is usually the one work.

“It’s an insult,” he stated. “But there’s no other job, so what can I do?”

The desperation confronting tens of tens of millions of landless Filipinos stems partly from insurance policies imposed by the powers that managed the archipelago for hundreds of years — first Spain, after which the US.

In a area outlined by upward mobility by way of manufacturing, the Philippines stands out as a nation nonetheless closely reliant on agriculture — a legacy of out of doors rule. Almost 80 years after the nation secured independence, the colonial period nonetheless shapes the construction of its economic system.

As a result of the US opted to not have interaction in large-scale redistribution of land, households that collaborated with colonial authorities retain oligarchic control over the soil and dominate the political sphere. Insurance policies engineered to make the nation depending on American manufacturing facility items have left the Philippines with a a lot smaller industrial base than many economies in Asia.

“The U.S. forced land reform on a whole lot of different countries in the region, Japan included, because of World War II,” stated Cesi Cruz, a political scientist on the College of California, Los Angeles. “But in the Philippines, because they were fighting on the same side, they did not want to punish their ally economically by forcing all these restrictions on them.”

Over the past half century in a lot of East and Southeast Asia, nationwide leaders have pursued a improvement technique that has rescued a whole bunch of tens of millions of individuals from poverty, courting overseas funding to assemble export-oriented business. Farmers gained higher incomes by way of manufacturing facility work, making fundamental items like textiles and clothes earlier than evolving into electronics, laptop chips and vehicles.

But in many of the Philippines, manufacturing facility jobs are few, leaving landless folks on the mercy of the rich households that management the plantations. Manufacturing makes up solely 17 p.c of the nationwide economic system, in contrast with 26 p.c in South Korea, 27 p.c in Thailand and 28 p.c in China, in response to World Bank data. Even Sri Lanka (20 p.c) and Cambodia (18 p.c), two of the poorest international locations in Asia, have barely greater shares.

The scarcity of producing and the lopsided distribution of land are a part of the rationale {that a} nation with among the most fertile soils on earth is plagued by hunger. It helps clarify why roughly one-fifth of this nation of 117 million folks is formally poor, and why almost two million Filipinos work abroad, from development websites within the Persian Gulf to ships and hospitals worldwide, sending house crucial infusions of money.

“You have an export strategy for Filipinos,” stated Ronald U. Mendoza, a world improvement skilled at Ateneo College in Manila. “This is really a middle class that we should have had in the country.”

Those that stay at house in rural areas usually plant and harvest pineapples, coconuts and bananas, laboring largely for the good thing about the rich, highly effective households that preside over land.

The plantation the place Mr. Sawan works is managed by Lapanday Meals, which exports bananas and pineapple to rich international locations in Asia and the Center East. Its founder, Luis F. Lorenzo Sr., was a former governor of Davao del Sur, a province in Mindanao, and a senior government at Del Monte, the multinational fruit conglomerate. His son Luis P. Lorenzo Jr., generally known as Cito, is a former agriculture secretary of the Philippines.

The founder’s eldest daughter, Regina Angela Lorenzo, generally known as Rica, oversees Lapanday from a company workplace within the Philippine capital, Manila, in a district stuffed with five-star inns, glittering eating places and luxurious automotive dealerships. She described her household as “a small player” in agribusiness.

“We employ people,” she stated. “We add tax revenue. We make productive use of the land.”

Her sister Isa Lorenzo owns artwork galleries in Manila and Decrease Manhattan — Silverlens New York, the place she options trendy Southeast Asian artists. An inaugural exhibit last fall put the highlight on “issues around the environment, community, and development,” together with the query: “Who owns the land?”

‘Our Ancestors Are Buried There’

Disputes over who owns the land dominate life for the Manobo, an Indigenous tribe within the highlands of central Mindanao.

For generations, members of the neighborhood lived alongside the banks of the Pulangi river, underneath the shade of teak and mahogany timber. They harvested cassava, hunted wild boar and caught fish from the river. They drank from a pristine spring.

“Our ancestors are buried there,” stated the chief of the neighborhood, Rolando Anglao, 49. “That is the land that we inherited from them.”

There, he indicated, gesturing towards the opposite facet of a busy freeway. The forest was gone. As a replacement was a pineapple plantation stretching throughout almost 3,000 acres. The land was ringed by barbed wire and guarded by an armed safety brigade.

In line with Mr. Anglao, the Lorenzo household seized the tribe’s land. One morning in February 2016, roughly 50 males arrived in vehicles and started firing their rifles within the air, sending 1,490 members of the tribe scurrying away, he stated.

Mr. Anglao, his spouse and their two sons had been amongst 100 households that reside in shacks constructed with plastic and sheets of corrugated aluminum on the shoulder of the freeway. They drink from shallow wells tainted with chemical runoff from surrounding plantations, he stated. Kids are continuously sick with amoebic dysentery. Tractor-trailers barrel by way of in any respect hours, their air horns blaring, carrying a great deal of sugar cane and pineapples to processing crops.

Through the years, the tribe has tried and failed to influence native prosecutors to pursue costs towards Pablo Lorenzo III, the president of the native firm that controls the plantation, and — not by the way — the mayor of the encircling city of Quezon.

This 12 months, the tribe secured authorized title from the Nationwide Fee on Indigenous Peoples, a authorities physique. However the fee has but to formally report the deed. Mr. Lorenzo has accused the tribe of supporting an insurgency, the New Individuals’s Military, stated Ricardo V. Mateo, a lawyer on the fee’s workplace in Cagayan de Oro. That has prevented the tribe from reclaiming the land by prompting an investigation by the Philippine army.

In the meantime, the safety cordon stays, with the tribe on the skin.

“It’s the power of Pablo Lorenzo,” Mr. Anglao stated. “He’s above the law.”

In an interview at metropolis corridor in Quezon, Mr. Lorenzo denied seizing the land.

“It’s a scam,” he stated. “Those people claiming that — they were never even on that land.”

Nonetheless, he acknowledged providing the tribe “a small amount of money” to relinquish its claims.

His household’s wealth traces again to his grandfather, who labored as a company lawyer representing American traders, Mr. Lorenzo stated. He personally owns 15 to twenty p.c of the corporate that developed the plantation, he stated.

Colonial Engineering

People didn’t create the inequality that defines the Philippine economic system. Spanish authorities allowed Christian missionaries to grab land whereas forcing natives to make onerous lease funds.

However after the US captured the archipelago following a battle with Spain in 1898, the colonial administration bolstered the uneven management of soil by way of commerce coverage.

Agribusiness ventures within the Philippines gained entry to the American market, freed from tariffs. In change, American business secured the appropriate to export manufactured items to the Philippines with out obligation. Tariffs on different international locations stored out merchandise from the remainder of the world.

America used the Philippines as a laboratory for financial insurance policies that had been contentious at house, amongst them pegging the worth of the nationwide foreign money to gold, stated Lisandro Claudio, a historian on the College of California, Berkeley. That stored the Philippine peso sturdy towards the greenback, reducing the value of American items and discouraging the creation of nationwide business.

Even after the Philippines secured independence in 1946, that fundamental association held. The nation had been decimated by World Conflict II, prompting the US to ship $620 million in reconstruction help. However the cash was conditioned on the Philippines accepting the indignities of the Bell Commerce Act, which perpetuated key points of the colonial association.

“The most odious part of that treaty was really the peso provision,” Mr. Claudio stated. “The Philippine government could not determine the price of the peso without consent from Washington.”

A powerful peso has remained a cardinal precept of Philippine coverage ever since, in distinction to neighboring international locations. From China to Japan to Thailand, officers have favored weaker currencies to make their merchandise cheaper on world markets, boosting their efforts to industrialize.

In the meantime, the highly effective and rich households that management enterprise have lacked incentive to innovate, not like in surrounding economies the place land redistribution has generated pressures for risk-taking and experimentation.

“Then you force the next generation to figure out, ‘What can we do to compete?’” stated Norman G. Owen, an financial historian affiliated with the College of Hong Kong. “But the United States didn’t do that in the Philippines, and the Filipinos didn’t do that to themselves, and here we are.”

‘A Tough Life’

On a mercifully overcast morning, with low grey clouds blotting out the tropical solar, a group of 48 staff pulled weeds from the soil of a Del Monte pineapple plantation in northern Mindanao.

The chief of the crew, Ruel Mulato, 43, was a third-generation plantation employee. His grandfather had labored for an American boss in a job that has modified little over the many years. Then as now, folks hunkered over the soil and used their palms, incomes too little to feed their households, forcing many households to borrow from mortgage sharks.

Mr. Mulato had seemingly escaped that destiny. He had labored as a nursing assistant on the island of Bohol, as a safety guard in Manila and as a crane driver in Saudi Arabia.

However when his spouse died all of the sudden in 2011, he moved house to maintain his daughter, then solely 4 years outdated.

He took the job that was obtainable — on the plantation.

He has remarried and has three extra kids. He was hopeful that they’d discover extra rewarding work.

“This is very hard labor,” he stated. “It’s a tough life.”