Evelyn Jefferson walks deep right into a forest dotted with the tents of unhoused Lummi Nation tribal members and calls out names. When somebody seems, she and a nurse hand out the opioid overdose reversal treatment Naloxone.

Jefferson, a tribal member herself, is aware of how crucial these kits are: Simply 5 months in the past, her personal son died of an overdose from an artificial opioid that’s about 100 instances stronger than fentanyl. The 37-year-old’s loss of life was the fourth associated to opioids in 4 days on the reservation.

“It took us eight days to bury him because we had to wait in line, because there were so many funerals in front of his,” stated Jefferson, disaster outreach supervisor for Lummi Nation. “Fentanyl has really taken a generation from this tribe.”

A invoice earlier than the Washington Legislature would convey extra state funding to tribes like Lummi which might be making an attempt to maintain opioids from taking the subsequent technology too. The state Senate unanimously accredited a invoice this week that’s anticipated to supply practically $8 million whole every year for the 29 federally acknowledged tribes in Washington, funds drawn partly from a roughly half-billion-dollar settlement between the state and main opioid distributors.

The strategy comes as Native People and Alaska Natives in Washington die of opioid overdoses at 5 instances the state common, in line with 2021-2022 Facilities for Illness Management and Prevention information that features provisional numbers. The speed in Washington is without doubt one of the highest within the U.S. and greater than 3 times the speed nationwide — however lots of the state’s Indigenous nations lack the funding or medical sources to totally deal with it.

Lummi Nation, like many tribes, faces a further problem in the case of protecting exterior drug sellers off their land: An advanced jurisdictional maze means tribal police typically can’t arrest non-tribal members on the reservation.

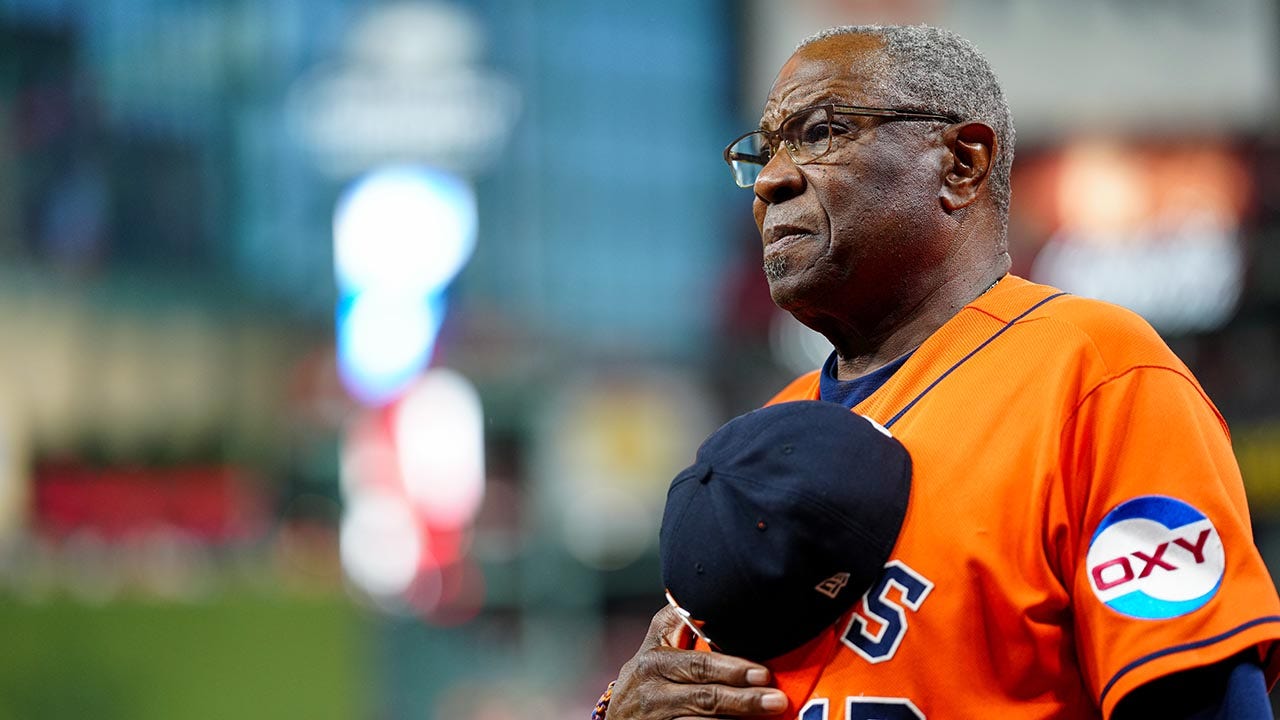

Evelyn Jefferson, a disaster outreach supervisor for Lummi Nation, stands at her son’s grave on the Lummi Nation cemetery on tribal reservation lands, Thursday, Feb. 8, 2024, close to Bellingham, Wash. (AP Photograph/Lindsey Wasson)

“What will we do when we now have a non-Lummi, predatory drug dealer on our reservation with fentanyl, driving round or on their property and are promoting medication?” stated Anthony Hillaire, tribal chairman.

In opposition to the backdrop, tribes such because the Lummi Nation, about 100 miles (161 kilometers) north of Seattle, say the proposed funding — whereas appreciated — would barely scratch the floor. The tribe of about 5,300 folks on the shores of the Salish Sea has already suffered practically one overdose loss of life per week this yr.

Lummi Nation wants $12 million to totally finance a 16-bed, safe medical detox facility that comes with the tribe’s tradition, Hillaire stated, and cash to assemble a brand new counseling heart after harm from flooding. These prices alone far exceed the annual whole that might be designated for tribes below the laws. The Senate has proposed allotting $12 million in its capital price range to the ability.

“We’re a sovereign nation. We’re a self-governed tribe. We want to take care of ourselves because we know how to take care of ourselves,” he stated. “And so we usually just need funding and law changes — good policies.”

The proposed measure would earmark funds deposited into an opioid settlement account, which incorporates cash from the state’s $518 million settlement in 2022 with the nation’s three largest opioid distributors, for tribes battling habit. Tribes are anticipated to obtain $7.75 million or 20% of the funds deposited into the account the earlier fiscal yr — whichever is larger — yearly.

Republican state Sen. John Braun, one of many invoice’s sponsors, has stated he envisions the funds being distributed via a grant program.

“If this ends up being the wrong amount of money or we’re distributing it inequitably, I’m happy to deal with this,” he stated. “This is just going to get us started, and make sure we’re not sitting on our hands, waiting for the problem to solve itself.”

Opioid overdose deaths for Native People and Alaska Natives have elevated dramatically up to now few years in Washington, with at the least 100 in 2022 — 75 greater than in 2019, in line with the latest numbers obtainable from the Washington State Division of Well being.

In September, Lummi Nation declared a state of emergency over fentanyl, including drug-sniffing canines and checkpoints, whereas revoking bail for drug-related fees.

The tribe has additionally opened a seven-bed facility to assist members with withdrawal and get them on treatment for opioid use dysfunction, whereas offering entry to a neighboring cultural room the place they work with cedar and sage. In its first 5 months, the ability handled 63 folks, nearly all of whom are nonetheless on the treatment routine as we speak, stated Dr. Jesse Davis, medical director of the Lummi Therapeutic Spirit Opioid Remedy program.

However actually thwarting this disaster should transcend simply Lummi Nation working by itself, stated Nickolaus Lewis, Lummi councilmember.

“We can do everything in our power to protect our people. But if they go out into Bellingham, they go out anywhere off the reservation, what good is it going to do if they have different laws and different policies, different barriers?” he stated.

The tribe has urged Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and President Joe Biden to declare states of emergency in response to the opioid crisis to create an even bigger security web and drive extra important sources to the issue.

CLICK HERE TO GET THE FOX NEWS APP

Within the encampment in Bellingham, Jefferson estimates there are greater than 60 tribal members, some she acknowledges as her son’s mates, whereas others are Lummi elders. She suspects lots of them left the reservation to keep away from the tribe’s crackdown on opioids.

When she visits them, her van stuffed with meals, hand heaters and clothes handy out, she wears the shirt her niece gave her the day after her son died. It reads, “fight fentanyl like a mother.”

“It’s a losing battle but, you know, somebody’s got to be there to let them know — those addicts — that somebody cares,” Jefferson stated. “Maybe that one person will come to treatment because you’re there to care.”